It was the German-born medievalist Ernst Kantorowicz who popularized the king’s two bodies as a way of understanding the early European state. The idea was that, when the legitimacy of governance rested on a single crowned head, the king became a double figure—an incorporeal body politic that symbolized the divine continuity of absolute power, but also a man who could get indigestion, die, and be succeeded. To put it more simply: There were many kings, but there was always a king. The Death Of Louis XIV, which dramatizes (a word used very loosely here) the last days of France’s longest reigning monarch, is in part an ironic riff on this concept, for the Sun King believed more than anyone in his divine right to power, but died of gangrene; furthermore, as if to prove Kantorowicz’s thesis, he held court almost until the moment he lost consciousness, fully dressed in his palace bed. But The Death Of Louis XIV is also an elegy for art cinema, as the title role is played—very poignantly—by the great Jean-Pierre Léaud, an icon of the French New Wave and star of the likes of Masculin Féminin, Out 1, The Mother And The Whore, and François Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel series. It’s such a conceptually fertile film that one wishes that it weren’t also a bore.

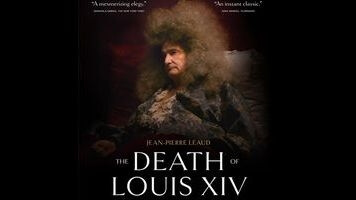

Sadly, this has become par for the course for the Catalan director Albert Serra, who began his career with Honour Of The Knights, a minimalist take on Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, and Birdsong, a reimagining of the journey of the biblical Magi as an absurdist black-and-white landscape film, but has since become a poor man’s Aleksandr Sokurov. To Serra’s credit, he isn’t a cultural reactionary like the Russian art-film titan, even if he has come to subscribe to an ersatz version of Sokurov’s morose and claustrophobic hallways of power. The Death Of Louis XIV is a refinement of his last feature, Story Of My Death, which interpreted the 18th-century crisis of reason as a meeting between Casanova and Dracula; it’s more pointed, populated, and sumptuous, with a vein of humor that seemed mostly lost on the earlier film. With his 2-foot-tall Phil Spector wig and his doll-like eyes, Léaud radiates vulnerability, doffing his hat with the assistance of a valet for an audience of courtiers. Serra’s figurations of the Western canon—Quixote, the Magi, Casanova—have always had a touch of Samuel Beckett to them, in that they are always either lost or waiting, and the Sun King is no exception.

It shouldn’t be a spoiler to say that the best quack doctors of Versailles—who sniff the king’s feet and prescribe donkey’s milk—are unable to save the ailing, elderly Louis XIV. Serra casts everything in a melancholy mood of imminent departure, with the king packed into his luxurious four-poster bed as though he were clothes in an open suitcase. But this bittersweetness is mostly meta-textual. The casting of Léaud, who is less a conventional actor than an utterly unique screen presence, turns Louis XIV into a devotional stand-in for what one presumes is meant to be a dying cinema. He continues to gesture regally and attempts to pass wisdom on to his great-grandson, the future Louis XV (Aksil Meznad), even as his body succumbs to a necrosis that no one can cure. Serra’s present style is conceptual and negative, as it derives all of its meaning from what it avoids, neglects, or crops out of the widescreen frame, rather than what it does—because what is does involves little aside from the placement of a camera in a dark room. This dismal framework turns The Death Of Louis XIV into a film-length longueur, begging for patience. There is a reason why Serra’s films are more widely read about than seen.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.