Throughout his career as an actor and producer, Michael Douglas has shown a remarkable skill for exploiting the cultural zeitgeist. At the height of the rebellious, anti-authoritarian '70s, he helped bring Jack Nicholson to the screen as an antihero for the ages with One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest. During an era of greed and sexual loathing, he starred in Wall Street and Fatal Attraction. But it's possible that no film he produced or starred in benefited more from its eerie parallels to current events than 1979's The China Syndrome: The jittery thriller about the perils of nuclear power arrived in theaters a mere 13 days before the disaster at Three Mile Island.

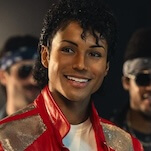

Co-written and directed by James Bridges, The China Syndrome famously predicted America's biggest nuclear fiasco, but its swinging-'70s milieu, its news-station hijinks, and the caveman sexual politics of its male newsmen all equally anticipate Anchorman. Jane Fonda stars as a spunky reporter aching to do hard news, but stuck serving as eye candy in degrading puff pieces involving zoo animals and singing telegrams. While doing an innocuous segment on a nuclear power plant, Fonda and dashing cameraman Michael Douglas (who also produced) stumble upon an accident that brings them into the orbit of Jack Lemmon, a true-believer power-plant employee who becomes an unlikely whistle-blower.

In every sense a film of its time, The China Syndrome is the kind of nervous thriller where powerful, pasty white men in expensive suits make sinister decisions in dark, luxurious offices and entrenched powers conspire against the interests of the little guy. There's an element of bitchy social satire, too, in its cynical take on the petty machinations of the news business and the way it fuses so seamlessly with entertainment that it becomes impossible to tell where one begins and the other ends. Like a lot of paranoid thrillers of the era, The China Syndrome boasts a visual style deeply indebted to documentaries, television news, and cinéma vérité. It maintains a certain distance from its characters both emotionally and physically, dropping them into giant sets that possess an almost Stanley Kubrick-like chilliness. Oscar-nominated production designer George Jenkins crafted a frightening, inhuman universe inside the power plant, full of blinking lights and huge machines but devoid of anything resembling warmth. It doesn't seem at all coincidental that Jenkins' credits also include All The President's Men and The Parallax View, two other exquisitely paranoid thrillers about dark doings among the Powers That Be. But ultimately, Lemmon's performance is what makes The China Syndrome work: The script contains its share of technical jargon and clunky exposition, but his subtle transformation from complacency to anger to panic tells the story in raw emotional terms. The China Syndrome is ultimately a story about how the potential for human error can trump science and reason, and few actors have ever been as unmistakably human as Lemmon.