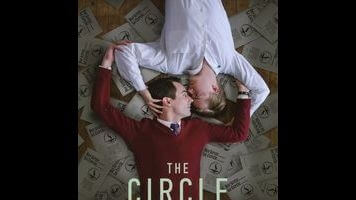

The Circle explores gay history through the story of one famous couple

The real-life story of Ernst Ostertag and Röbi Rapp—a couple since the ’50s and the first men to be married in Switzerland—serves as The Circle’s through-line to reconstruct roughly a decade’s worth of gay Swiss history. The narrative-doc hybrid begins in the present, with the real Rapp singing a song Ostertag wrote for him long ago. “I’m so strange,” he warbles, but the following present-day images belie that claim, instead quickly laying out a long-established domesticity between two life partners whose newspaper-and-tea routines radiate unfeigned warmth.

Director-co-writer Stefan Haupt toggles between present-day documentary footage and reconstructions of what’s being recalled, splitting his time between the two modes more or less evenly. Largely of the standard talking-head variety, the doc segments work precisely because of Ostertag and Rapp’s keen overlapping memories and rapport (they are, simply, the Platonic ideal of an adorable old couple), and because, at least for non-Swiss viewers, the story they have to tell is novel.

The Circle refers to a tri-lingual publication founded in 1932 as a lesbian-oriented periodical, one quickly converted by the pseudonymous “Rölf” (the actor Karl Meier) into a “homophilic” concern. As the couple and supporting interviewees explain, Switzerland never had the equivalent of Germany’s infamous Paragraph 175 or any codified, institutionally enforced homophobic legislation, meaning Zurich became a mecca for continental gay life: The Circle’s annual balls were the only large gay events of their era. That certainly didn’t mean an end to homophobia, with the publication cooperating with the police on self-censorship and gay life occupying a not-quite-public gray zone whose boundaries were increasingly encroached upon by the police.

Haupt deftly collapses the line between past and present, as when Ernst revisits the site of the annual balls. When he walks up the stairs of the present-day building, the film seamlessly cuts to his younger fictional self (Matthias Hungerbühler) entering for the first time. The reenactments themselves aren’t entirely satisfactory: understandably hemmed in by budgetary constraints, saddled by ineloquently compressed historical exposition presumably not covered in the documentary interviews, rushing from one event to another. It’s perhaps inadvertent but still unfortunate that the only scenes which remotely approach intercourse or any explicit contact are followed by legal or murderous fallout; the sex equals punishment/death link, while probably not intended, makes for a retrograde undercurrent.

The romance between Ernst and Röbi acts as a microcosmic example of a larger debate whose broad terms remain familiar. A teacher from an intellectual family, Ernst remained closeted until his parents’ death, acutely aware they wouldn’t want to learn about his orientation, while Röbi was openly gay and lived in comfortable candor with his mother from an early age. As years pass, the debate takes on a more urgent tone, with Rölf (Stefan Witschi) exhorting monogamy and discretion while his younger staff members find his ideals increasingly outmoded. This split—between openness and closeted, and more broadly a debate about how to live gay life in a public, rigidly straight space—remains germane, a familiar motif in films as otherwise up-to-date as, say, the recent Lilting.

The Circle delivers a large amount of information painlessly, capturing a chapter in gay history at the last moment before a decisive push to make out-and-proud the norm took over. Inevitably fascinating, it’s weakened by hammering a rush of incidents into a shape suggesting over-hasty melodrama rather than vivid history. Its fascinations compromised by its clunkiness, the film is a necessary niche history that serves well enough as a primer, placing it just a cut above coasting on good intentions.