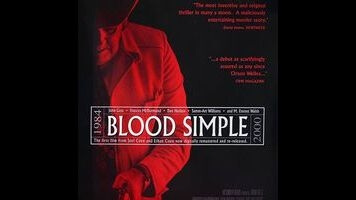

The Coens’ magnificent noir debut Blood Simple returns again to theaters

Every 16 years (at least so far), the Coen brothers’ 1984 debut, Blood Simple, gets a theatrical re-release. Back in 2000, the marketing hook was a so-called “director’s cut,” though Joel and Ethan had encountered no interference regarding the original release; they were just a bit embarrassed, in retrospect, by what they perceived as their amateurish touch in certain spots, and re-edited the film in order to obscure or remove those alleged infelicities. Whether artists should ever “improve” work they presented as complete many years earlier is a contentious subject—see, for example, The People Vs. George Lucas—but the Coens have clearly decided to stick with their revised cut, as that’s what’s rolling back into theaters this week, showcasing a new 4K restoration. (It’ll also be the sole version included in a forthcoming Criterion Blu-ray edition.) While purists may grumble—and astute readers may detect a grumbling subtext to this very paragraph—any excuse to see the Coens’ magnificently moody neo-noir on the big screen is welcome.

As is often the case in film noir, neo- or otherwise, infidelity sets the plot in motion. Weary of Marty (Dan Hedaya), her abusive husband, Abby (Frances McDormand, in her screen debut) has been carrying on an affair with Ray (John Getz), one of the bartenders at a tavern Marty owns. Unbeknownst to Abby and Ray, however, Marty suspects their relationship, and hires a private detective, Loren Visser (M. Emmet Walsh), to confirm it. Visser subsequently agrees to kill the cheating lovers, and provides photographic evidence that the deed is done. Unbeknownst to Marty, however, the photos Visser shows him have been carefully doctored, and Abby and Ray are still very much alive. Several more permutations of “unbeknownst to X, however” then follow, as all four of the characters confidently make decisions based on false information and/or mistaken assumptions. Most thrillers keep viewers in the dark about certain details for a while, in order to create mystery or suspense. Blood Simple, by contrast, reserves various elements of surprise for the increasingly hapless folks on screen. Only the audience has a clear picture of what’s really going down.

Decades later, the Coens would employ that same basic idea to comic effect in Burn After Reading. Here, their sense of humor comes through in extremely bitter irony—the movie’s final line is priceless—and a few knowing visual jokes, like a shot in which the camera, traveling the length of Marty’s bar at drink level, finds its path blocked by the head of a passed-out patron and serenely glides up and over the obstacle, continuing on its way. (Cinematographer Barry Sonnenfeld later became a notable director in his own right, best known for helming the Men In Black franchise.) The brothers instantly demonstrate their knack for coaxing beautifully offbeat performances from their actors, too; Walsh in particular is delectably sleazy, speaking his lines in a sneering Texas drawl that makes every word sound as if it’s turned rancid. And then there’s Carter Burwell’s score—his very first—which lacks the grandeur of his orchestral work in later Coen films like Fargo, but manages to evoke a palpable sense of dread with a simple piano theme. Insofar as their name signifies an aesthetic, the Coen brothers were fully formed right from the get-go.

That makes it all the more maddening, for the purists (grumble grumble), that it remains impossible to see Blood Simple as originally released, unless one can somehow watch one of the 35mm prints struck in 1984. Due to home-video licensing issues, the VHS and laserdisc releases substitute a truly lame version of “I’m A Believer” for the Four Tops’ “It’s The Same Old Song,” heard several times during the film. That was corrected in the 2000 re-release (which is what’s currently available on DVD and Blu-ray), but at the cost of Joel and Ethan’s retroactive cosmetic surgery, visible again in this latest incarnation. The changes themselves are quite minor, scarcely detectable to anyone who hasn’t committed Blood Simple to memory, and they do improve the movie a bit, honestly; their main effect is to significantly reduce the screen time of an actor named Samm-Art Williams, who’s definitely the weak link in the cast (and hasn’t acted since 1991, according to the IMDB). Still, it’s the principle of the thing. Artists sprucing up their work many years later, merely out of vanity—as opposed to a genuine director’s cut that restores alterations imposed by a studio—is the equivalent of digitally altering old photos to make yourself look less dorky. Blood Simple didn’t need that sort of hindsight tweaking. It’s a trailblazing masterpiece in any form.