The Coens swipe at religion, counterculture, and Hollywood in Hail, Caesar!

“We’re not talking about money—we’re talking about economics!” Hail, Caesar!, Joel and Ethan Coen’s broadest comedy since The Ladykillers, lampoons Christian and leftist dogma by pitting straw men and stuffed shirts against whatever passes for common sense in the Coensverse, embodied by yet another of the sibling duo’s beloved plainspoken cowboys. The Coens, who skew crypto-conservative, can’t take anything resembling an ideology or counterculture seriously, but here they defer to the logic of “good feels right,” which is just as much of a non-answer as the jargon that gets recited by the movie’s assorted religious authorities (three priests, a minister, and a rabbi) and Communists. Like the often overlooked A Serious Man, this is all about the absurdity of crises of faith. However, the Coens’ fondness for intentional anti-climax—put to pointed and poignant use in movies like Inside Llewyn Davis, No Country For Old Men, Barton Fink, and A Serious Man—gets the better of them.

Perhaps it seems like over-thinking to quibble with the ideological talking points of a movie that mostly dawdles from one skit or cameo to another, interspersed with the occasional song-and-dance number, and which contains one of the best comic set pieces of the Coens’ career: a director and his recently re-cast lead trying to work through a single awful line of dialogue (“Would that it were so simple”) while filming a turgid melodrama. But like so many of the brothers’ later films, Hail, Caesar! ends where it started, with the characters having huffed and gnashed their teeth and changed nothing—and whereas their great movies side with loser heroes, turning failures into studies of people struggling to hold on in the face of apparent meaningless, this one seems to be out to teach them a lesson to leave well enough alone. To all those who would characterize the Coens as smug misanthropes: Enjoy this bounty of ammunition.

Set in Hollywood in the mid-1950s, Hail, Caesar! sometimes feels like the Coens’ 1941, which is to say that its central joke is that it’s playing the fears of its era at face value: That Tinseltown is a Sodom and Gomorrah of vice and anti-American subtexts, and that Soviet submarines lurk in American waters, signaled by leftist study groups. It’s all extremely on-the-nose; after all, this is the kind of film that introduces a gay movie star with a butt-bumping sailor-themed musical number called “No Dames.” The period setting is sketched in broad strokes (fittingly, the only real-life filmmaker name-checked here is Norman Taurog, director of Elvis vehicles and Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis movies), giving the Coens a chance to play with dated and outmoded film techniques: wipes, bird’s-eye-view matte paintings, painted backdrops, unconvincing model submarines, and, in the movie’s most perverse act of homage, a very long driving scene of questionable urgency.

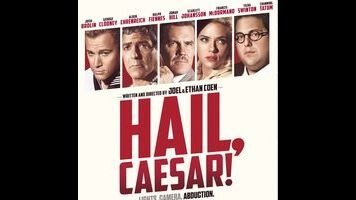

The aforementioned crises of faith are represented by Eddie Mannix (Josh Brolin), a devoutly Catholic studio executive who is mulling over a lucrative job offer from Lockheed as he races around town to keep his projects running on schedule and his leads out of the gossip columns, and Baird Whitlock (George Clooney), the hard-partying star of a religious epic (also called Hail, Caesar!), kidnapped by reds who turn him on to Karl Marx and against his employers at the unsubtly named Capitol Pictures. What they both need, per the Coens, is a smack of aw-shucks common sense, which comes in the form of stuntman-turned-cowboy-actor Hobie Doyle (Alden Ehrenreich, downright revelatory). Doyle’s folksiness and thick twang are played for laughs, but his Western bona fides—complete with a mouth full of false teeth from his days as a horse wrangler—are revered in the manner of No Country For Old Men’s Sheriff Ed Tom Bell or The Big Lebowski’s nameless stranger. (Compare to Inside Llewyn Davis’ phony cowboy Al Cody, the most pathetic loser in a movie full of them.)

Along with the usual putdowns of highfalutin artsy-fartsy types (a dog named Engels; a pronunciation of “rodeo” that rivals The Big Lebowski’s “thorough” and Burn After Reading’s “memoir” at establishing snoot-hood), the movie takes swipes at something the Coens have never shown much of an interest in before: Christian iconography, represented by the ridiculous film-within-the-film Hail, Caesar!, which “tastefully” depicts Christ only from the back, as a robed figure with a head of impeccable long, straight blond hair. There are other movies seen in various stages of production on the Capitol lot, none completely convincing as period pastiche, some funny as send-ups of bad filmmaking: a musical starring an Esther Williams type named DeeAnna Moran (Scarlett Johansson), who refers to her mermaid costume as a “fish ass;” Merrily We Dance, directed by ascot-wearing priss Laurence Laurentz (Ralph Fiennes); bits of Doyle’s singing cowboy movies and the latest from Gene Kelly-esque dancer-athlete Burt Gurney (Channing Tatum, showing off a surprisingly passable singing voice).

Add in a string of one-scene cameos (everyone from Jonah Hill to Christopher Lambert), wacky gags (like having Tilda Swinton play rival gossip columnists), and an extended scene in which Mannix holds a meeting with religious leaders to consult on Hail, Caesar!, only to have an Orthodox priest complain about the realism of the chariot scenes and a rabbi shrug every answer, and what you’ve got is one overstuffed movie. Though the Coens are celluloid-shooting visual classicists, their films often have unusual or lopsided structures, introducing major characters very late or taking narrative detours halfway through. And as with so much about this writer-director-producer-editor duo, their best and worst instincts are inseparable. The same aversion to classical form that’s produced the filmmakers’ most ingenious shifts and denials of closure turns Hail, Caesar! into a grab-bag of ideas in various stages of formation, full of dead ends and seemingly pointless sequences, peppered with out-of-nowhere narration by Michael Gambon. Somewhere in there are stretches of the Coens’ funniest comedy since The Big Lebowski; it just takes a little patience.