James Franco has a predilection for dashing among movies, books, experiments, and academia like a charismatic but perpetually late TA. It may sound exhausting, but it’s hard to deny the results—not their quality, mind, but that the results even exist. Franco makes a lot of art, both good and bad. But no one provides a bolder example of the vanishing lines that used to separate movie stars, fringe artists, and working actors. Other personalities react to the diminished star caste system by agreeing to appear in low-rent thrillers for extra cash; Franco, meanwhile, shepherds NYU grad students as they collectively adapt a series of poems.

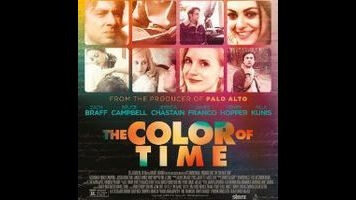

That’s the genesis of The Color Of Time, shot during breaks in Franco’s blockbuster freelancing as a tribute to and adaptation of poet CK Williams. A dozen filmmakers, many of them students Franco met at NYU, receive the writer-director credit, but this isn’t a collection of shorts. Instead, the filmmakers make Williams himself a character and cut together slices of his life using his poems as source material, creating a speculative approximation of autobiography. Franco plays an older version of Williams in the ’70s and ’80s, living with his wife Catherine (Mila Kunis), while other actors play Williams as a boy and a young man.

The earliest set scenes feature floating, kid’s-eye view shots of a young boy interacting with his luminous mother, played by Jessica Chastain, and his sterner father—in other words, so close to Terrence Malick’s The Tree Of Life that it almost reads as parody. Nakedly derivative as the imitation is, it’s also an understandable starting place for young filmmakers trying to evoke poetry more than traditional film narrative. It’s more successful as imitation Malick than other passages are at mounting pure cinema, emphasizing images and feelings over plot and characterization. A teenage Williams’ visit to a hooker, for example, plays out in underlit close-ups full of artsy blurring, evoking boredom rather than provoking whatever dreamy discomfort the filmmakers have in mind.

The better moments of Color Of Time make use of the ringer cast Franco was able to assemble, however momentarily. There are incidental pleasures in Bruce Campbell showing up to play a blowhard in a shabby convenience store, or in the low-key warmth of Franco’s interactions with Kunis, or with Zach Braff as his sickly friend. It’s a shame, though, that all of this fails to either coalesce into a strong point of view or combine to form a more kaleidoscopic vision of this poet’s life and work. Like so many movies before it, this one fails to make the onscreen processes of thinking, watching, and writing especially compelling. Still, Franco and his famous friends clearly helped to make The Color Of Time out of love, and it’s hard to work up much dislike for a movie so focused on the art of poetry—or one that employs more female directors than the 100 biggest grossers of 2014 combined. It’s another James Franco result, even if it’s more admirable in theory than interesting in execution.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)