The infrastructure supporting the direct market of comic shops has been shaky for years, making the impact of the COVID-19 crisis all the more severe. Stores around the country are closed, distribution is paused, and publishers have ordered creators to stop working as they reevaluate their release schedules. The global pandemic is hitting retailers, creators, and publishers hard, and as we near the end of the first month without new comics, there’s still a lot of uncertainty about how the industry is going to recover and what it will look like after this crisis ends. A.V. Club comics writers Oliver Sava and Caitlin Rosberg break down what’s being done now to offer support, and explore potential avenues for recovery.

Oliver Sava: In the immortal words of Clint Barton: “Okay… this looks bad.” Distribution of new print comics is on hold and the major publishers aren’t releasing digital copies (although DC Comics continues to release reprints and digital-first comics on ComiXology). And we don’t know when it’s going to end. DC is exploring some

new distribution options with plans to start releasing new comics April 28, but with shelter-in-place orders extending around the country,

many retailers are frustrated by DC’s decision to put out content when stores are cut off from customers.

To help ease the ongoing burden on retailers, many publishers are making new comics returnable so shops won’t take a hit on any unsold product. Vault Comics will send PDFs of upcoming releases to customers who buy gift cards from comic shops. TKO Studios gives retailers 50% of profits made from digital purchases when customers choose a store at checkout, and I know stores have started getting those checks because my local shop posted a picture of the first one it received.

Comics aren’t going anywhere, but the landscape might look very different when publishing resumes. In a piece published last month on his Comichron website, John Jackson Miller writes about previous periods of severe disruption and how the industry evolved to survive. Each of these periods resulted in innovations that helped drive comics forward as both an industry and art form, and the rise of the internet has brought about huge changes since the last seismic comics crisis of the ’90s.

Caitlin, you’ve spent a lot of time exploring distribution models outside of the direct market. Will we see new tactics to monetize webcomics?

Caitlin Rosberg: I was a dedicated webcomic reader for almost ten years before I started my first pull list [an agreement between a customer and retailer to reserve certain comics for purchase each month—Ed.], so in some ways my head and heart are going to go to webcomics first. They’ve always been faster to pivot and shift strategies, partly because it’s a lot easier for them; print publishers are large organizations and not particularly agile, often beholden to an even larger organization above them. Webcomics as an industry have already gone through several large shifts to chase stable monetization, moving away from ad sales and cyclically embracing webcomic platforms and publishing cooperatives.

A lot of webcomic creators are relying on Patreon now, which isn’t without risk but does afford some stability and helps build a sense of community with patrons. I know some individual creators that work on traditionally published comics rely on Patreon for income too, which says a lot about the state of the industry before the current situation. We’ve already seen traditional publishers like Oni, Dark Horse, and First Second use Kickstarter either for direct fundraising or by identifying popular self-published projects that could be lucrative. Reader-supported hosting sites like Webtoon and Tapas prove that webcomic platforms have changed and matured in really interesting ways: They support creators that don’t want to dedicate a lot of time to the technical challenges of hosting a comic online and want to leverage a massive pre-existing user base that’s self-identified as a webcomic reader.

I’m not sure how many of these industry-wide tactics are going to change in these new, trying times. Individual contributions from patrons and Webtoons supporters will likely go down and Kickstarters will struggle as readers tighten their belts. Nothing is recession-proof, but webcomics have weathered economic storms before, and the overall strategies in place are relatively sound ones. The real strength is that the diversity of the creators and their needs are answered by the flexibility of the funding options. People can and do successfully tailor things to their own specifications.

A lot of that flexibility isn’t available to traditional print publishers, even with creator-owned content and graphic novels. Do you think there are any webcomic strategies or concepts that print publishers or creators could adopt to help mitigate future risks? Do you think times like these might push more people toward online self-publishing?

OS: To answer your first question: It’s already happening. AWA Studios, the new endeavor from former Marvel publisher Bill Jemas and editor-in-chief Axel Alonso, launched on March 18, two weeks before Diamond Comics froze distribution. The next week, AWA announced it would be releasing its books online in a vertical scrolling format à la Webtoon and Tapas, and it has since released digital “episodes” on both of those platforms as well as on the AWA website.

It’s a savvy move in response to the halt on print comics, and the quickness of the execution makes me wonder if this wasn’t a plan for AWA Studios all along. Maybe they had already scoped out Webtoon and Tapas as distribution avenues to publish web-optimized versions of comics after their print issues had already gone on sale, essentially turning these existing platforms into their version of Marvel Unlimited or DC Universe. I don’t know if the company had that foresight or if this was truly a quick response tactic, but it’s one that I could see gaining traction with other publishers. Oni and First Second have serialized comics digitally before releasing printed collections, and we might see others follow suit, especially as printed single issues become less profitable.

I think a lot of people are going to be forced toward online self-publishing when publishers tighten their belts, and I’m curious to see what emerges when creators take distribution into their own hands. We have one example in Panel Syndicate, created in 2013 by artist Marcos Martín and writer Brian K. Vaughan as a way to distribute new titles with DRM-free digital comics purchased at a price dictated by the customer. Other creators have also released books on Panel Syndicate, and last week, it blessed us all with the surprise-drop of a new series by Martín and seven-time Eisner Award-winning writer Ed Brubaker: Friday.

Will Panel Syndicate grow to host more comics? Will other creators launch their own platforms to get comics to readers without a middleman? You have to have a Martín/Vaughan level of industry cache to make something like Panel Syndicate truly profitable, so that’s not really an option for up-and-coming creators who want to get people to read their work and ideally make some money in the process.

These are alternative distribution models to get content to readers, but what can be done to create a better distribution system for retailers? Diamond has a monopoly on U.S. comics distribution, and without competition, it hasn’t had any pressure to evolve with the times. What would you like to see them do differently as the industry recovers?

CR: This is really the big question for me. I love a lot of what Panel Syndicate has done—and as you said, it’s proven to be a sustainable plan in the long run. But the problem of Diamond’s tight hold on print distribution for monthly issues is one of several big elephants in the room that have shaped the industry into one that screeches to a halt very quickly. It wasn’t always this way—for decades there were more than a handful of distributors that ferried comics from publishers to comic shops and readers. Diamond has been promising technology updates to better serve everyone for a long time, but they’ve been slow to come (if they arrive at all), and yesterday we learned that one of their directors has bailed on the company to enter the healthcare industry, which doesn’t exactly inspire confidence.

A quick glance at comics Twitter will show you a slew of folks rightfully saying that this is a prime opportunity to overhaul the distribution of comics. There’s even some folks who think this may bring the end of the direct market entirely, but I’m not so sure that’s likely or even wise. There’s a lot to be said about having the ability to consume stories in monthly chunks, and the structure of having a friendly neighborhood comic shop to help people find a next new favorite comic is something I honestly want for everyone.

But a single bottleneck in the pipeline is unsustainable in the long run, and this has finally brought that issue to a head. Some publishers (like Iron Circus Comics) opt out of Diamond entirely, and I’d love to see more publishers do the same. I really wonder what purpose Diamond is really serving publishers, comic shops, and readers these days, and what benefit any other distributor might bring. Figuring out how to distribute books themselves is a tall order for publishers, especially smaller ones, but it seems like it would be worth saving the money that Diamond cuts out of the equation—and perhaps more importantly, could lead to two other much needed changes: a reduction in the number of titles printed each month and better policies around returning books.

Right now comic shops are flooded with dozens of titles from the biggest publishers, many of which don’t sell very well. Because publishers don’t have to worry about books getting returned from shops and costing them money, strategically it makes sense to overprint and offer variant covers to shops in exchange for larger orders that may not completely sell. Getting a better handle on what books do well in what markets and making the relationship between publishers and shops a more consistent partnership is a recipe for success for both groups, and Diamond is very much standing in the way of that.

We’ve spent a lot of time talking about the industry and larger organizations, and not as much about the individual people that make comics so incredible. Do you think there will be any creator- or reader-driven changes coming out of this time period?

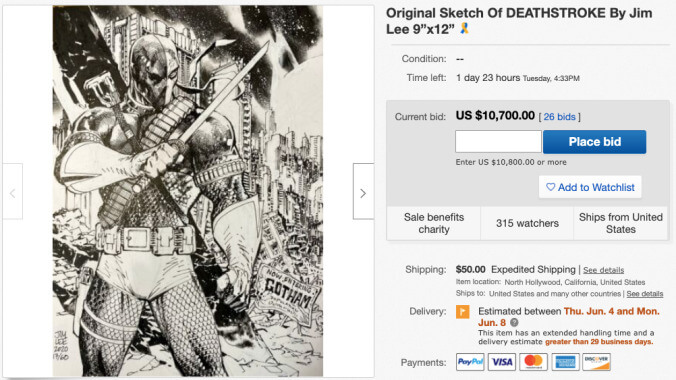

OS: We’re definitely seeing an outpouring of support from both creators and readers for those impacted by the crisis. #CreatorsForComics launched last week, a social media initiative where creators auction books, scripts, art, chats, and other prizes to benefit the Book Industry Charitable Foundation (BINC), which provides emergency relief to comic shops and bookstores. Before that, DC publisher and chief creative officer Jim Lee started his own charity auction for BINC on eBay, featuring pieces from himself as well as other superstar artists like Arthur Adams and Bryan Hitch. (DC Comics also donated $250,000 to BINC.) It’s refreshing to see the community rally like this, but fundraising is a short-term solution for retailers that are facing a struggle with no clear endpoint.

A couple weeks ago, creators started talking about a new Marvel/DC crossover when this is all over as a way to accelerate sales, and I’m very curious to see if the wall built between these two companies over the past 20 years will start to crack. It feels very much like a long shot, but maybe the sense of community spreading across the industry will inspire editors to bury the hatchet. It’s also worth noting that this crisis comes at a time when young readers exposed to comics during the ’10s graphic novel boom are entering adulthood, so publishers would be wise to cater to this large population, ideally by putting out work by creators actually in that age range.

One of the big reader changes retailers are concerned about is increased adoption of digital comics, and it’s a major reason why publishers didn’t just put new releases on ComiXology when Diamond paused distribution. I know a lot of people who have already transitioned to digital streaming services like ComiXology Unlimited, Marvel Unlimited, DC Universe, and Hoopla because of the cost of print comics, and they’re willing to wait a bit to read these stories if it saves them money. And a lot of people are going to be cutting down on their spending. The economic impact of the COVID-19 crisis will continue changing how people choose to consume entertainment as more cost-effective options present themselves, but I also hope that this period of social distancing reminds comic fans of the community fostered by retailers and inspires them to continue supporting their local shops.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.