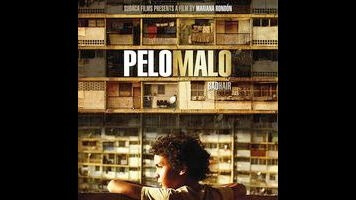

The coming-of-age story Bad Hair is all dispiriting realism, no catharsis

Coming-of-age stories don’t get much more demoralizing than Bad Hair, from Venezuela, which amounts to an extended power struggle between a single mother and her 9-year-old son that the boy can’t win. On the one hand, it’s hard not to admire writer-director Mariana Rondón, who pulls no punches in her portrait of a woman less concerned with loving and caring for her child than with enforcing societal norms; there’s not a trace of sentimentality in the film’s conception of motherhood, to the point where charges of misogyny would be likely had a male filmmaker been at the helm. On the other hand, though, brrrr! Bad Hair can best be described as expertly depressing—a subcategory of art cinema that seems worth the punishment only when the gloom is counterbalanced by at least a few transcendent moments. No such moments ever surface here, however, apart from a brief fantasy during the closing credits. It’s just a long, slow downward spiral, rendered all the more dispiriting by how mundane it generally appears.