The Competition looks inside one of the world’s most elite film schools

The French film school La Fémis, which accepts only around 1 percent of applicants to its directing program, has a well-earned reputation as one of the most exclusive institutions of its kind. It promises world-class instruction and facilities to budding filmmakers, provided they speak near-fluent French and can pass its notoriously grueling, capricious, and competitive undergraduate admissions cycle—which, even for the lucky fraction who advance to the third and final round, usually ends in rejection. Claire Simon’s documentary The Competition offers a close look at this process. It is, perhaps unavoidably, an insider’s view (Simon, like so many French filmmakers, has taught at La Fémis), appealing directly to one’s vicarious interest in elite institutions, their eye-rolling gatekeepers, and the fresh-faced young things who are foolish enough to come under said gatekeepers’ mortifying scrutiny.

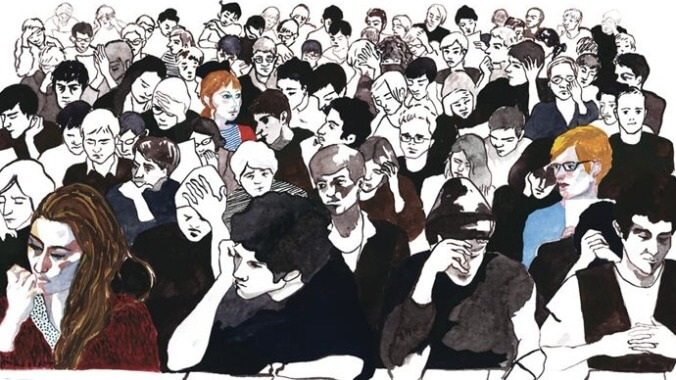

La Fémis itself was created in the 1980s, under the presidency of François Mitterrand, as a replacement for the storied national film school IDHEC, with the goal of cultivating new generations of French filmmakers and preserving France’s cultural capital in the world of film. Unlike most of the top-tier film schools (London, Łódź, NYU, UCLA, VGIK, and so on), it has a strict age limit; generally, applicants have to be no more than 27, and are given only three chances to get in. The Competition, which was shot during the 2014 admission cycle, opens with hundreds of these would-be film students filing into an auditorium for their first round—a written exam that asks them to analyze a 10-minute clip from the Japanese director Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s miniseries Penance. Even at this early stage, the quirky process has hints of cruelty; as the time limit runs out, the lights in the hall are shut off, forcing the remaining applicants to scratch their essays to completion in total darkness.

The small fraction who survive this first round move on to individual examinations. In one, applicants are given 45 minutes to write a story based on random, sometimes ridiculously cryptic prompts (examples offered here include “The car drives slowly along the Quai de Montebello” and “She said to me, ‘I am a horse’”); this test seems to exist mostly to measure an aspiring filmmaker’s ability to pull ideas out of their ass while evading the well-tuned bullshit detectors of a three-person jury. Applicants to the directing program get a studio tryout with a script, a crew, and actors, and are judged both on their performance on set and the resulting footage. A seven-hour written test for screenwriters is mentioned, but never seen.

The Competition doesn’t clarify that these rounds actually occur over the span of something like four months. Nor does Simon’s observational method provide context, history, a sense of location, or, in most cases, even names—apart, that is, from the names of the filmmakers, distributors, movie theater owners, and industry professionals who judge applications and introduce themselves at the start of every session. The approach is sometimes reminiscent of the great documentarian Frederick Wiseman’s portraits of institutions in action—a little bit of administrative deliberations of At Berkeley here, a little bit of the cringe of early classics like High School there. Though Wiseman, a deeply critical observer of social machines, would never allow himself to be so complicit.

But though The Competition lacks critical distance, what it offers, in spades, is the engrossing experience of watching other people endure pressure and humiliation—a thrill not unlike that of addictive reality TV, though one presumes that everyone involved would retch at the comparison. One applicant completely blanks after being asked to name a favorite movie—or just any film off the top of her head. Another makes it to a directing tryout, only to be colorfully dismissed (behind his back, thankfully) as the kind of arthouse poseur who “masturbates to his own footage with Robert Bresson’s Notes On The Cinematograph in the other hand.” A third presents such a striking combination of off-putting personality and obvious talent that it leads into a heated debate over whether they can deny someone admission just because they all hate his guts. When a talkative applicant to the producing program is praised by one admissions juror for his long, energetic answers, another snidely counters, “I felt like he was on coke.”

Is this student too pretentious? Was his exam essay excessively personal? Trying too hard? Not hard enough? Should they be looking for students who are good communicators? Aren’t a lot of great filmmakers just difficult weirdos? Behind closed doors or on the balcony during regular smoke breaks, the conversations captured in The Competition return to the same questions about personality and potential, without explicitly interrogating the project of La Fémis—that is, without broaching the possibility that a school that was designed to replace a supposedly outmoded way of teaching film could have its own ossified values. (The closest it comes to criticism might be by accident, as flippant cracks about student diversity leave the lingering impression that the people at the top of an elite European academy might, quelle surprise, be a bunch of casually racist and classist snobs.) But mostly, one is left thinking: Could I write the essay that impresses Alain Bergala and his roomful of miserable film programmers and magazine editors? Do I have the personality that will charm the director of The Adventures Of Felix? Could I hack it at La Fémis? In that sense, The Competition is as much a brochure as an investigation.