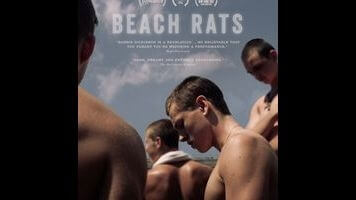

The Coney Island mood piece Beach Rats tells the double life of a closeted teen

Call it Bro Travail. Beach Rats, Eliza Hittman’s eroticized study of young male bodies and repressed sexuality along the arcades of Coney Island, owes a sizable debt to the films of Claire Denis (particularly a certain desert-set Herman Melville adaption), going so far as to copy the extraordinary French director’s cryptic fragmentation of close-ups and eye lines. On a conceptual level, it’s immaculate: the druggy summertime exploits of a closeted, often shirtless 19-year-old (Harris Dickinson, a really impressive unknown) and his gaggle of no-good macho buddies rendered as a grainy mixture of skin, smoke, and gazes. But Hittman (It Felt Like Love) turns out to be a conventional storyteller; despite her evocative styling and Dickinson’s surprisingly assured lead performance, her sophomore feature remains confined in monotonous, psychologically shallow coming-of-age-drama indiedom. It’s a shame, as Beach Rats has one of the year’s best parting shots. In a more fleshed-out film, it might have been transcendent.

But at least it has a look nailed down: skillfully filmed on Super 16mm by the French cinematographer Hélène Louvart, with a mise-en-scène of underlit, disorientingly snap-shotted body parts—fingers, abs, cheekbones, asses—that immediately establishes something of a microcosm of touch, curiosity, and objectification. The opening sequence strikes a promising note, as Dickinson’s character, Frankie, takes shirtless selfies in a mirror, his phone’s flash streaking across the dirty glass. Unemployed and still living at home on the far edge of Brooklyn, he spends his afternoons and evenings with his friends—smoking weed, picking up girls, and picking pockets on the crowded boardwalk—and his nights on hookup, chat, and webcam sites, generally going for older guys. His dad is dying of cancer and his mom (Kate Hodge) seems too drained to deal with either Frankie or his younger sister.

Whether it’s at home, in the semi-anonymity of a hookup, within the confines of his delinquent entourage, or in his relationship with Simone (Madeline Weinstein), a girl he meets on the boardwalk early in the film and begins quasi-dating, there seems to be no space where Frankie doesn’t feel the need to withhold, and one of the most intriguing qualities of Dickinson’s performance is how he intuits his way through the character’s unwillingness to articulate himself. But within the context of such a deterministic, unpoetic script, these subtleties end up being a surface effect—and the same goes for the movie’s air of non-judgment and all those suggestive close-ups and artsy, lingering shots of young douchebags in motion. Suffice it to say that Frankie’s cautious first attempt at merging the sides of his double life does not end well.

Denis, from whom Beach Rats borrows so much (along with a few moves from Ratcatcher and Morvern Callar-era Lynne Ramsay), is a fairly radical filmmaker; whatever meaning her films have is inseparable from the way they handle bodies and abstractions. But with its boilerplate subplots and interchangeable supporting characters, Beach Rats could really look like anything and still arrive at the same conclusions. Thankfully it looks like this.