The Cult Of We expertly charts the disastrous arc of Adam Neumann’s WeWork

Wall Street Journal reporters Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell explain, better than anyone else, how the real estate company ballooned to a $47 billion behemoth

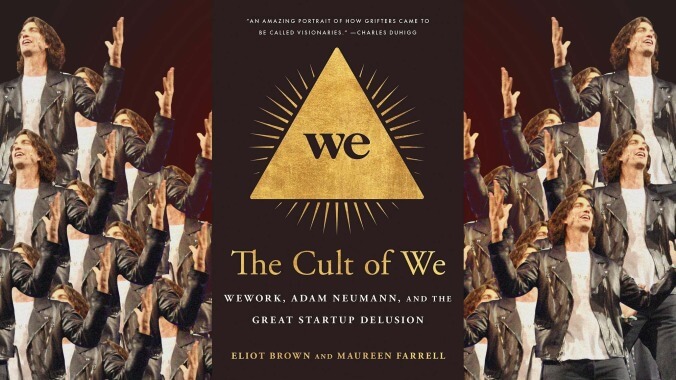

Not even two years after WeWork’s spectacular collapse, its story has been told numerous times. In January of last year—only three months after the company’s disgraced founder and former CEO, Adam Neumann, was ousted—there was a podcast series on the debacle hosted by former Marketplace host David Brown. In October 2020, New York Magazine reporter Reeves Wiedeman published his book, Billion Dollar Loser, an engaging profile of Neumann and the company. And this March, Hulu released a dreadful documentary, WeWork: Or The Making And Breaking Of A $47 Billion Unicorn. Into this saturated market, Wall Street Journal reporters Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell, who cover start-ups and IPOs respectively, are publishing The Cult Of We: WeWork, Adam Neumann, And The Great Startup Delusion. Thankfully, being first isn’t always better.

The coverage of many Silicon Valley companies, even (and especially) in their demise, tends to center on the personalities of their founders. This makes a certain amount of sense and coincides with such leaders often being given too much power despite not being very good at their jobs. In this regard, Neumann is as desirable a figure as they come. He turned a successful office rental business into a massive, directionless corporation. He is married to Gwyneth Paltrow’s cousin. He got a sizable investment from Ashton Kutcher, who he met through The Kabbalah Centre. He really loves smoking weed. Even in the context of the young Silicon Valley elite, he sticks out as a uniquely entitled, uniquely childish, uniquely stupid man. Most importantly, maybe, he’s tall. (All books about start-ups, including this one, love mentioning how tall people are.)

There’s plenty of information about Neumann’s exploits in The Cult Of We, but what’s included is not merely titillating trivia. It’s not immaterial, for example, that Neumann once told the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed bin Salman, that the two of them, along with Jared Kushner, were going to remake the Middle East, or that he said a Middle East peace treaty would be signed in a WeWork office space. Brown and Farrell also detail reports from those who managed Neumann’s private flights, which included one trip where passengers spit tequila on each other and another where “there was so much Marijuana smoke in the cabin that the crew was forced to pull out the jet’s oxygen masks and put them on.” A fine-in-theory ban on meat at WeWork was a hard sell, as Neumann barely talked to anyone who would be tasked with managing the initiative before he made the announcement; what’s more, his constant use of private jets and multiple cars undermined the environmental commitment that originally allegedly motivated the ban.