The Dan Rather/60 Minutes scandal gets ploddingly dramatized in Truth

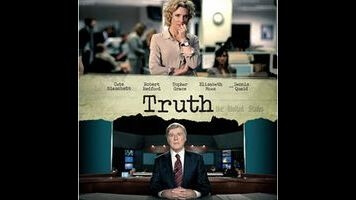

Early in the docudrama Truth, writer-director James Vanderbilt does a newsroom spin on the classic caper picture’s “assembling the team” scene. He’s already introduced Mary Mapes (Cate Blanchett), a veteran broadcast news producer dedicated to chasing tough stories. One by one, the movie adds Mapes’ trusty trio of sidekicks: resourceful researcher and political radical Mike Smith (Topher Grace), retired colonel and military liaison Roger Charles (Dennis Quaid), and associate producer Lucy Scott (Elisabeth Moss), whose main job is to ask questions like “What do you mean?” and “Why is that?” so that the other three can deliver exposition and opinion. That’s the nature of Truth: a promising build-up, dead-ending into prosaic pontification.

The story this group breaks—on the prestigious, award-winning CBS news magazine 60 Minutes, no less—involves President George W. Bush’s service in the National Guard during the Vietnam War, asking whether he first pulled strings to avoid the draft and then failed even to meet the basic requirements of his posting. Truth is mostly set in 2004, in the months leading up to Bush’s re-election, and if nothing else, it’s a reminder of how high the stakes were back then, and how uncertain the outcome. With public sentiment starting to turn against the Iraq War, and Democratic challenger John Kerry up in the polls, the group “Swift Boat Veterans For Truth” attacked Kerry’s war record—previously considered a political asset—which to Mapes and 60 Minutes made the president’s own military past fair game. On September 8, 2004, the program’s Wednesday edition aired a report on memos appearing to show that Bush had shirked his sworn duty as a Guardsman. But by the next day, the internet was abuzz with right-wing bloggers and amateur sleuths offering evidence that the documents were fakes.

Truth’s contention—drawn in part from Mapes’ own memoir Truth And Duty: The Press, The President, And The Privilege Of Power—is that no one has ever convincingly disproved the memos’ authenticity. But the movie’s larger point is that even if Mapes’ team was duped by their source, the substance of the documents had already been corroborated. Moreover, Truth notes that CBS’ broadcast and cable news rivals devoted an uncommon amount of airtime and resources to reporting on 60 Minutes’ downfall, rather than following up on Bush’s time in the Guard. The film is fundamentally about the dangerous downfall of old media institutions, and how calculated political attacks and the prioritizing of profits by media conglomerates can lead to a world where the powerful no longer feel obliged to answer questions from a journalist as accomplished and well-known as CBS anchor Dan Rather.

But while that theme’s strong, its presentation isn’t—with a few exceptions. Robert Redford does make a terrific Rather. He’s doing an interpretation, not an impression, which means he incorporates some of Rather’s clipped Texas twang but is mostly just “Robert Redford,” an American icon who himself has aged out of relevance to large portions of the population. Vanderbilt uses Redford cleverly in Truth, drawing on his lingering star power to demonstrate how Mapes herself used Rather for as long as she could: as her trump card for any uncooperative sources. (“It’d mean a lot to Dan,” she says in the movie whenever people are on the fence about going on the record.)

Truth also brings some critical perspective to what went wrong within CBS, not letting 60 Minutes off the hook entirely for squirrelly sourcing. In the movie, Mapes keeps having to make compromises: forced to run the story earlier than she’d like because the network was trying to avoid accusations that they were springing an “October surprise” on Bush, and then pushed to trim a key contextual interview because it was too long and too “boring.” When Truth really gets cooking, it has some of the insider snap of Broadcast News, showing the mad rush as a piece comes together, and how tight deadlines can lead to major mistakes.

But there’s an indication of what’s going to go awry with Truth in its very first scene, which has Mapes in a post-scandal debriefing, delivering her resumé to her inquisitor in one fast-talking line—not for his benefit, but for ours. Blanchett is commanding as ever as Mapes, but a lot of what she’s asked to do in the movie is lecture, hector, and explain. And Truth’s repeated attempts to tie the producer’s anger to growing up with an abusive father comes across as too pat and blunt. It’s not enough to hear that Mapes was beaten by her dad as a girl for being too precocious; the movie also later has her explode at the right-wing media because they “smack us” for “asking questions.” (The outburst is followed by an awkward silence from her colleagues, lest we all missed the connection.)

It’s not just Blanchett who carries the burden of underlining Truth’s message. Grace can be effective in the right role, but Vanderbilt does him no favors by having Smith be the guy who stands up to the CBS brass to tell them what they’re doing wrong—complete with detailed statistics, which Grace is meant to produce as though he were delivering a spontaneous rant. Again, what the character and the movie has to say is important, and as a behind-the-scenes look at one of the major newsroom crises of the past 15 years, Truth is fascinating and often exciting. But the film lacks the qualities of great drama that make it feel like it’s unfolding right in front of the audience. Instead it has well-known actors in costumes, reciting talking points. No one can complain that Truth buries the lede. It’s all lede.