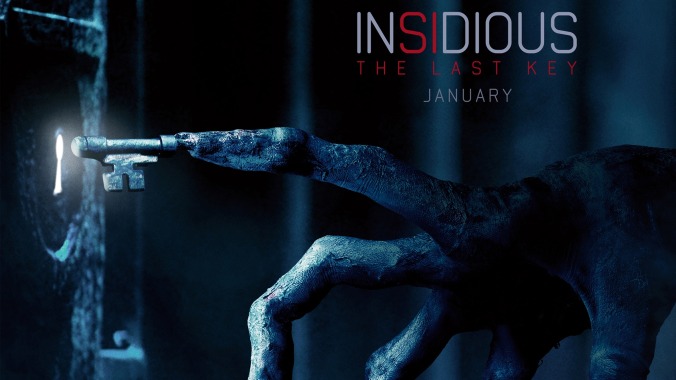

The dark and creepy gets dull and creaky in Insidious: The Last Key

The success of Insidious, the low-budget horror flick about a family trying to rid itself of ghosts and demons with the help of a trio of kooky paranormal investigators, and its more classical and polished follow-up, The Conjuring, turned director James Wan into the modern multiplex’s leading producer of formulaic but effective haunted-house scares, cranking out more sequels and spin-offs (à la Wan and screenwriter Leigh Whannell’s earlier torture-porn soap opera Saw) than he could ever helm himself. But underneath the technical expertise that Wan and protégé directors like David F. Sandberg have brought to many of these projects are premises as moldy and interchangeable as the rambling American Colonial and Craftsman-style homes where most of these movies are set—dusty collections of creepy dolls, jump scares, dark cellars, and other public-domain genre tropes. Without the snazz of Wan’s maturing style, they end up looking like Adam Robitel’s Insidious: The Last Key, a clumsy and internally confused sequel to Insidious: Chapter 3 (which was, uh, a prequel to the first film) that offers strictly mechanical jolts.

Ironically, the most unusual-by-Hollywood-standards feature of this series is also one of its indestructible constants; as the psychic and demon expert Elise Rainier, Lin Shaye makes for an unconventional star, not only because she’s a woman in her seventies, but because her character bit the bullet three films ago. Set mostly in 2010, The Last Key finds Elise and her grating, Best Buy-Geek Squad-looking comic-relief sidekicks Specs (Whannell) and Tucker (Angus Sampson) traveling to fictional Five Keys, New Mexico (“We’ll unlock your heart”) to investigate paranormal happenings at her own childhood home on behalf of its new owner, Ted Garza (Kirk Acevedo), a spooked trucker-hat hick who always looks like he just crawled out from under an old GMC Sierra. The house itself is like any other cursed property in the Wan-iverse: stained wallpaper, inadequate interior lighting, a huge and sinister basement.

Character motivations in haunted-house films rarely make sense, but Ted claims a surprisingly believable reason for not just getting the hell out at the first sign of the supernatural: He’s sunk his savings into the house thinking he could flip it. (It follows that the characters most likely to fall prey to evil lurking in long-vacant properties would be working-class; the idea is loaded with fresh potential and commentary, though, with the exception of Brad Anderson’s Session 9, it remains unexplored.) But this turns out be something of a red herring, as does the 1950s-era fallout shelter below the house and the abandoned penitentiary that looms nearby (Elise’s dad, we learn, was a tyrannical assistant warden), a looming symbol of the movie’s wasted potential. For the most part, The Last Key opts for the very familiar—more scurrying ghouls with personal-space issues, more yawning doors, and another trip into the Further, the black-light-and-fog-machine limbo dimension that exactly resembles a Halloween haunted house. The original film somehow managed to make the Further scary; here, one can practically taste the vaporized glycol.

There’s a certain amount of magician’s craft and showmanship that goes into a film like this: The tricks are simple and repetitive, and once the audience figures out how they work, they’re bound to get bored. Robitel, who previously directed the found-footage The Taking Of Deborah Logan, tries his darnedest to synthesize Wan’s surface effects: the period decors (there’s an extended prologue set in 1953); the wide-angle shots of murky hallways; the curtain-black shadows; the Spielbergian touches, including a promising (but pointless) opening shot that pulls back from the keyhole of an iron gate into a matte-painting-esque view of the house and prison. But he is as lost in Whannell’s script as the characters, who traipse around, trapped in their own stupefacient Further of bad acting, puzzling plot twists, and wince-inducing comedic banter, never thinking to look over their shoulders. Horror is the domain of fascinating subtexts, but there’s not much going on below the surface of The Last Key’s garbled screenplay, which adds subplots about child abuse, serial killers, and psychological trauma into the familiar mix of “don’t open that door”s and “it’s right behind you”s. The end result seems misguided at first glance, but, upon closer examination, doesn’t make a lick of sense. Perhaps that’s for the best.