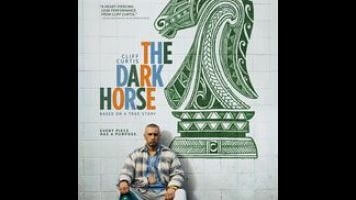

The real-life chess champion with mental health problems is such potent bait for actors, and the inspirational teacher narrative so enduring to movie producers everywhere, that a combination of the two was probably inevitable. (Searching For Bobby Fischer’s dueling mentors: Not inspirational enough!) It was less inevitable, though, that the movie fusing that particular character with that particular narrative would be set in New Zealand, feature a gang of burly, menacing Maori criminals as villains, and focus on an inspirational mentor who spends much of the movie homeless. The Dark Horse may not entirely work as a film, but it has an unexpected amount of gritty idiosyncrasy on its side.

The sorta-homeless guy at its center is Genesis Potini (Cliff Curtis), a New Zealand speed-chess prodigy who, as the movie begins, is wandering into a curiosity shop, drawn in by the chess sets in the window, before he’s escorted off to a mental hospital. Once released, he briefly takes up residence with his brother Ariki (Wayne Hapi), an aging gang member. Ariki is grooming his son Mana (James Rolleston) to join up with his gang—their matching leather jackets and husky physiques suggest an American biker gang, but none of them appear to ride motorcycles—while Gen, as his family calls him, quietly suspects the boy might benefit from a different environment.

Gen also reaches out to the Eastern Knights, a local chess club for kids, and becomes a coach, fixated on getting them to a chess tournament just six weeks away. Aided by more traditional advisors, and living on the streets after Ariki kicks him out, Gen throws himself into chess training, which focuses his sharp mind, sometimes beleaguered by bipolar disorder. Curtis, a longtime character actor (at least in movies; he’s a lead on Fear The Walking Dead), commits to the role without resorting to show-offy tics, making the most of his chance to distinguish himself from Clifton Collins Jr. once and for all.

Much of the movie eschews the hamminess its material might otherwise encourage. Most crucially, the chess-club kids assembled by writer-director James Napier Robertson (an actor himself whose credits include a 2004 stint as a Power Ranger) have no trace of child-actor precociousness. Though the movie doesn’t provide the space for them to emerge as individual characters (or the context to even discern which of them are especially good at chess), as a group they sell the potentially moony-eyed concept of rowdy kids who are enraptured when a near-stranger shows them a carved wooden chess set. As easily as mentorship seems to come to Gen, and as easily as many of the kids take to guidance, The Dark Horse builds on a challenging idea about just what kind of a “crazy” leap is needed to mount an inspirational-teacher regimen in these circumstances—and how being an inspiring mentor doesn’t put a roof over Gen’s head.

Indeed, the movie is most interesting as a look at the struggles of the underprivileged in New Zealand. Robertson shoots the country in a way that brings bucolic magic-hour warmth to often rundown surroundings; even a chess tournament shot in drab interiors has a certain glow. It’s this slightly anthropological approach that brings Ariki’s gang into narrative prominence. While the relationship between Gen and Mana is affecting, the pervasive gang menace veers toward the ridiculous, if only because the movie supplies such a loathsome villain in the form of the gang member in charge of initiating Mana.

The intensity these scenes generate probably isn’t unrealistic, but it does throw the movie off balance, especially considering how well it handles some of its climactic chess business. The final match is just about as gracefully underplayed as this kind of movie can handle, and also doesn’t function as the end-all be-all of the story. Where it goes after that, though, is more indicative of the movie’s full plate of characters and concerns than a truly satisfying conclusion. But with more Kiwi gang initiation rituals than most chess dramas, and more chess than most hardscrabble stories of poverty, it certainly has novelty to fall back on.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.