The Day After is a rare misstep from South Korea’s prolific master of the mundane

Americans of a certain age, for whom The Day After conjures terrifying images of nuclear apocalypse (thanks to a 1983 TV-movie of that title), can rest easy. Nothing remotely momentous ever happens in the films of Korean director Hong Sang-soo, and The Day After—one of three features he premiered last year, arriving in U.S. arthouses after On The Beach At Night Alone and Claire’s Camera—is even more inconsequential than usual. That needn’t necessarily be a bad thing, since Hong’s obsession with small-scale, mundane human behavior contributes to his best work’s considerable charm. But he’s taken this approach too far in The Day After, a lazy shoulder shrug of a movie that never bothers to work out who its characters are, what they want, or why their ostensible problems should be of interest to anyone else.

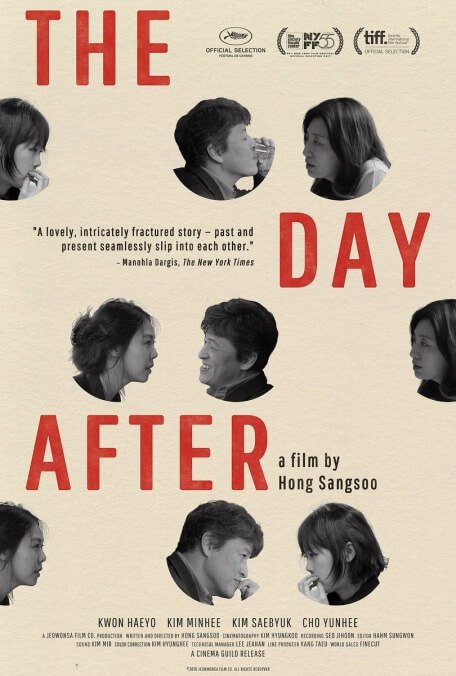

Even the film’s structure—usually Hong’s forte—seems atypically imprecise, as if he started out with one idea and then abruptly changed course. (Reliable reports indicate that he now more or less writes his screenplays as he goes along; though the actors aren’t improvising, they only see their dialogue an hour or two before the scene in question is shot.) Initially, there are repeated time jumps, cutting back and forth between an adulterous affair and its aftermath. Soon, though, we’re firmly in the present, as the cheating husband, Bongwan (Kwon Hae-hyo), who runs a small publishing house, hires a new employee named Areum (Kim Min-hee) to replace Changsook (Kim Sae-byeok), his ex-lover. Changsook took a powder one or two months earlier, but Bongwan’s wife (Cho Yun-hee) has only just now learned about the affair, via a poorly hidden love letter, and doesn’t know Changsook either by name or by sight. She only knows that Bongwan has been fucking his secretary, and promptly storms to the publishing house to give Areum a truly uncomfortable first day on the job. And that’s before Changsook unexpectedly comes back.

Summarized like that, The Day After sounds as if it might make a terrific screwball comedy, especially since Hong can be very funny indeed (albeit generally in a less antic, more depressive way). Instead, he’s made a strangely desultory melodrama that eventually pivots on the not exactly riveting question of whether it’s rude to fire someone who’d quit earlier the same day and then been talked into staying. Shot in black-and-white, the film looks magnificent in stills, but Hong’s use of the camera has strayed into autopilot territory, randomly panning from one actor to the other over the course of long, repetitive, faintly dull conversations (including one earnest undergrad-style bull session about the nature of reality and whether it can be captured in words). Kim Min-hee, who’s done consistently excellent work in Hong’s last several films (particularly the superb Right Now, Wrong Then), looks utterly adrift here, above and beyond Areum’s natural confusion about the messy personal drama into which she’s inadvertently wandered. And the film’s epilogue, set some indeterminate time later, in which Bongwan fails to recognize Areum and they repeat their first bland getting-to-know-you conversation almost word for word, feels like deliberate trolling.

That last bit, too, might potentially have been fun, had Hong worked to craft repetition that’s still engaging on the surface level, rather than soporific once and then soporific again. It’s perhaps not a coincidence that many of his best films are diptychs, with the second half recapitulating the first half in some way; even if he’s extemporizing the movie, there’s essentially a rough draft (part one) that’s later refined (part two). The Day After, which is mostly linear, plays more like recent Woody Allen, conceived in haste and deemed “good enough” after the first pass. If you make three movies a year, inventing them all on the fly, at least one is apt to be a whiff.