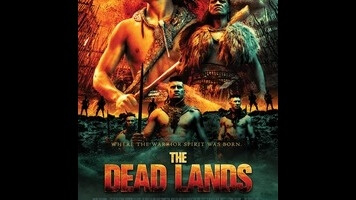

The Dead Lands views a rarely explored culture through a dusty narrative lens

Faced with a choice between the unique poetry of landscape and myth and the recognition factor of monomyth, the Māori action flick The Dead Lands mostly opts for the latter. Abstract, synth-scored finale notwithstanding, it’s another plodding take on the hero’s journey, with New Zealand’s rugged terrain cut into an indistinguishable mass of karst rock and dry grass. But when a movie is set in pre-colonial New Zealand and it’s about a teenage chieftain taking on a tribe of warmongers with the help of a man-eating ogre, can it really be considered generic?

The Dead Lands follows 16-year-old Hongi (James Rolleston) as he leaves tribal grounds in search of the dastardly Wirepa (Te Kohe Tuhaka). Along the way, Hongi meets up with a fearsome cannibal (Lawrence Makoare, best known for playing orcs) with no name and no tribe, who dispenses survival tips and general life advice in between butchering corpses for meat. Padding out this “leave home, grow wise” structure are skirmishes with Wirepa’s band, whose identical dress anachronistically suggests military uniforms. Even in this pre-modern tribal setting, the old costume design cliché of equating evil with mass production holds true, with Wirepa presented as a proto-fascist.

Though it’s framed in universal (i.e., hackneyed) terms, The Dead Lands deals in cultural values—ranging from ancestor worship to cannibalism—that are anything but. At its worst, this disconnect registers as exotica; at its best, it gives the movie’s choppy action an edge. Director Toa Fraser’s disorganized, zoom-heavy handling of gruesome melee combat gets repetitive, but the eye-bulging and tongue-flicking that precedes every exchange of blows doesn’t. Maybe it’s just the novelty, or maybe it’s the fact that these dances of intimidation, as stylized as butoh, resist being taken on any terms except their own.

With its Māori-language dialogue and its symbolic emphasis on the mere—the teardrop-shaped blade of Māori warfare—The Dead Lands stresses authenticity, which has the unintended effect of highlighting its one-size-fits-all storytelling. The good king (Hongi’s father) dies; a semi-supernatural guide (the cannibal, who is believed to be immortal) joins the hero; a temptress appears out of nowhere. Perhaps it’s the landscape that’s put so many Kiwi filmmakers, from Vincent Ward to Jane Campion to Peter Jackson, into the mindset of myth. Fraser and writer Glenn Standring aren’t working on that deep a level, though. For the most part, they mine a vein that’s been tapped out ever since screenwriting gurus got crazy about Joseph Campbell.

The problem with this kind of universal narrative is that, like the cult of the golden ratio, it emphasizes formulas at the expense of those expressive qualities that actually make art and entertainment. Even Jackson’s Lord Of The Rings movies—which are about as monomythic as movies get this side of Star Wars—understand that templates aren’t the reason why stories have potency. It’s difference that matters; a movie this outwardly unusual—set in a tribal past, spoken in a language that’s rarely heard on screen—should have more of it.