When we met, I was 18 and Brian Chankin was at most 25. At the time, he looked like a vampire. I remember he was living in the video store behind a 19th-century decoupage screen and smoking Gauloise cigarettes that he kept in cartons in the freezer. There were animals, too, mostly birds. He always had parrots and conures, and after the video store moved next to a skate shop on Milwaukee Avenue and he moved into an apartment upstairs, he started breeding zebra finches in the second bedroom. By then Brian had quit smoking cigarettes, and his freezer was always full of dead finches.

Eventually, I moved above the video store too, along with some other members of the gang, all of us paying rent to a wizened old lady who had owned the building since who knows when. For a time, this way of life seemed to me to be the center of the universe. We subsisted on fried plantains and Cuban sandwiches. I was reading a lot, watching three or more movies a day, and dressing like I lived in another era. We were weirdos with something akin to communal values, but probably not all that different from most people in that we were all a lot younger than we thought we were.

Brian named the video store Odd Obsession, after a Kon Ichikawa movie that no one ever rented. Most of the people who ever worked there were volunteers who shelved DVDs a few times a week for free rentals, but we were all fluent in a certain dialect, a movie-ese of Putney Swope and mondo. This language was magic, because anyone who spoke it was your friend. You knew the canon, the muddy rear-projection classics, the art freakouts, and the stoner specials: Japanese children’s television, weird docs, various psychoactive copyright infringements from Turkey. There were the crazes for all things Japanese and Korean, the Charles Bronson years, and all manner of fractious debate about the store’s category system and what exactly distinguished Mavericks from American Classics and Italy from Italian Genre.

Probably it was no way to run a business, and things only got more confusing after Brian got a partner in the store who was also named Brian. The floor was rarely swept by anything more than the dragging belly of the store cat, and the unheated back room stank of vinegar from the old 35mm film prints that were stored there alongside accumulating boxes of unsorted VHS rarities that came to resemble the final shot of Raiders Of The Lost Ark. This was all some time ago, more than a decade. But it’s no bold assertion on my part to say that much of what we feel nostalgia for is the kind of inconvenience that creates a more eclectic and interesting reality.

I worked there on and off for about six years, but it existed for 16, all the way up until this April. It was never a utopia, but I think more than a few of us saw the store even at its most farcical as playing some part in a struggle against dystopian forces. If you were going with your friends to see Miami Vice in the dingiest theater in Chicago, hooking up a video projector to show obscure films on the side of a garage, or just talking strangers into watching old B-movies, it was easy to imagine that your most abstract social and artistic values could be manifested in the physical world. You could pluck something you loved off a shelf, and in that sense it was a dream.

If you didn’t grow up sometime between pan-and-scan and the director’s commentary it might seem unfathomable that a seriously good video store could be a revelatory mecca of cine-mania and something like a democratic institution. Certainly it was the only place where high and low and new and old ever really mixed. Video stores were essential to a movie freak’s self-education, and the best were even more alluring than movie theaters, a sensory overload of covers, posters, standees, and rows in clashing colors. If you were a kid, it was the place where you were most likely to glimpse forbidden objects. The best video store clerks were saints with Gen-X halos—exactly as opinionated and knowledgeable as record store clerks, but far less likely to roll their eyes.

Odd Obsession was in this sense always an anachronism. Among the Last Great American Video Stores, it was unusual for having been founded well into the era of DVDs; most of the others had been in business since the golden period of the 1980s. By the time it opened in 2004, in a small basement unit that was across from the Steppenwolf Theatre and not far from the site of Cabrini-Green, the video rental industry was already being threatened by rent-by-mail, which was dominated by Netflix. Streaming was still some years away.

At that time the store was just Brian, who had decided to turn his personal DVD and VHS collection into something that looked like a business. I’m not sure there was ever a long-term plan. Memberships were free, rentals were cheap, and if you were renting several titles, you were usually given a discount. From the beginning, the strangest people would hang around the store. It was a place where you met magicians, communists, struggling novelists, amateur pornographers, eccentric pack rats in their 70s and 80s, indie-circuit wrestlers, unhinged homicide detectives, and former Black Panthers who knew everything about kung fu. Some of these regulars were living fables.

I remember one, a creepy accountant with bad breath and a comb-over, who would meticulously describe the movie he was looking for. It was always the same description, and the movie he was always describing was Damage, the Louis Malle film. To which he would invariably say, “No, I’ve already seen Damage.” And there were also teenagers and film students who would spend hours and hours picking through shelves of Rainer Werner Fassbinder movies or Japanese horror films in that tightly packed basement, which was decorated with pictures of Laura Gemser, Italian lobby cards, and fake sticks of red dynamite and yellow nitramite likes the ones Jean-Paul Belmondo wrapped around his head at the end of Pierrot Le Fou.

I was one of them. The truth is, I always thought working in a video store was cool. At the time, I was selling DVDs at a Barnes & Noble. I had graduated from high school just a few months prior and moved to Chicago. I guess I inserted myself into the life of the store, but I was hardly the first or the only one. There was Antoine, who stuck with the store longer than any of us, and Sarah, who had Klaus Nomi eyebrows. Joe started around then. He was a kid with translucent skin, red hair, and an encyclopedic knowledge of all things X-rated. I guess he looked even more like a vampire than Brian then, but it was the 2000s, and a lot of people were trying to look like vampires.

Joe was almost as much the face of the store as Brian for many customers. He pretended to hate a lot of things, but was protective of his adult-movie auteurs, guys like Chuck Vincent and Shaun Costello, who might have had unrealized ambitions beyond making skin flicks and hardcore one-day wonders. Our heroes tended to be marginalized or misfit, and there was probably some amount of projection going on. When Brian called me to talk about the end of the store, neither of us could figure out how many people had worked or volunteered at Odd Obsession over the years. It could’ve been as many as a hundred.

Early on, there were attempts to run the store as something like an art gallery, which every business that smelled like incense was trying to do in those days. When the store moved to Milwaukee Avenue after a couple of years, it became one of those places that guidebooks told hip tourists to visit. It outlived the guidebooks, just as it outlived most of the video rental industry in America and any illusions that Brian or anyone else ever had about running a profitable enterprise. It would be a lie to say that the store’s early years didn’t benefit to some extent from various closings, going-out-of-business sales, and corporate agonies. But it always felt like it might be the last video store on Earth.

It always felt like it might be the last video store on Earth.

It’s probably a common experience that the past begins to seem more and more like an alternate dimension as you get older. We worked part-time jobs to pay the rent or went to school full-time. A few had sidelines that were not yet legal for recreational use in the state of Illinois. I got really good at getting fired from regular jobs but managed to work in a laundromat for a year. Brian was constantly getting into new things, a succession of monomanias. He became a DJ, started listening to a lot of reggae, hosted a late-night radio show. Eventually, he fell in love with hand-painted art from Ghana, especially the wild, gruesome, one-of-a-kind movie posters.

We fancied ourselves to be all kinds of things: trash apologists, amateur historians, sommeliers of movies in which Italian women were strangled to spectacular music. If you were willing to run the register or pull discs from behind the counter according to a confounding letter-number system (G for genre, C for country, N for nothing) managed by antique software, it was because those little white labels with directors’ names on them and those shelves that sagged and leaned under the weight of hundreds of empty DVD and Blu-ray cases represented something that mattered.

You were stumping for campy action movies or hicksploitation films, trying to spread the gospel of underappreciated directors like Allan Dwan, Jerzy Skolimowski, and Alan Rudolph or self-aware underground filmmakers like the Kuchar brothers or Jon Moritsugu. You had a handmade Oscar Micheaux T-shirt or a personal stash of rare bootlegs that looked like they were recorded in mud. You wanted to share strange wonders like A Thief In The Night or Confessions Of An Opium Eater or hard-to-see classics that had not yet been Criterion-ized. You threw in a more adventurous pick for free if a customer was having second thoughts. Chances were you thought of yourself as struggling against a media monoculture. It was probably pretentious, but in my experience pretension is a very effective motivator for young people.

Yet as much as it was a haven for movie freaks, Odd Obsession was still mostly a video store for everyone else—regular people who wanted to find the grossest horror movie or a decent rom-com based on some human algorithm. To this day, when I get recognized by strangers, it’s almost always because of the video store. Sometimes they wait to hear my voice. Then they ask, “Didn’t you work at Odd Obsession?” I used to get embarrassed by this because I’d been on TV. I don’t anymore. Strangely, people always remember what movies you recommended to them.

Katie Rife, who’s a senior writer at

The A.V. Club, was part of Odd Obsession for about three years, starting right after I left, though she’d been a customer since the mid-2000s. At the time, she was also working at Facets, which was another video rental store with an enviable library of rare and foreign titles. You have to believe me that there is a fraternity that exists among people who have worked at video stores. When we congregate at film festivals, we swap stories about our video store clerk days, eccentric customers, or the rental habits of celebrities.

Though Katie and I have worked together for some time, we’ve never actually talked about Odd Obsession, which I think meant a lot to both of us. I called her up, and we reminisced about our similar experiences in different eras of the video store: the Zen of sorting and shelving the DVD case; the store cat, who was loved unconditionally; the mollifying presence of Brian; the bittersweet feeling of returning to the video store’s third and final location, which was just a few doors down from the second and still on Milwaukee Avenue, seeing volunteers you didn’t recognize, and wanting to tell them that this used to be your life.

Lindsay Denniberg was there after both of us, at that third location. She first came in as a VHS collector and was eventually one of the select few to have been employed full-time at the store. I called her to talk about those years, after Brian had stepped back from managing the store to focus on collecting and selling Ghanaian movie posters. The store became famous for his posters, which covered entire walls that were visible from the street. In fact, if you look up pictures of Ghanaian movie posters online, a lot of the results will be pieces that were commissioned for the video store. You can tell because instead of the name of a video club in Teshie or Madina, it will say, in white curly script, “Odd Obsession Movies, Chicago.”

We all tell the same stories. How your time at the video store mapped across some significant part of your life, whether it was a mid- to late-20s quarter-life crisis or that idealized passage into adulthood when the skies were the color of denim, the nights were long and cool even in summer, and you went to parties that stank of all the bodies gathered there. How in the best years it was kept afloat by some sort of anarchy. How you never felt like you were just helping out but actually running the video store. There was drama that only appeared dramatic to those involved and those that knew them well enough to relish gossip. There were rivalries. People sometimes left on bad terms. The thing is, not one person remembers when they actually started working at Odd Obsession.

Talking about the end of the video store now feels about as appropriate as reading a coroner’s report at a memorial. It had moved to a new storefront in 2015 and been through a lot more bad times than good. There were fundraisers and attempts to run it more like a regular business. The future was incredibly bleak, as it had been even in the years I spent there. I had seen it on the brink of closure many times. But the store was always rescued at the last moment. The pandemic wasn’t the only nail in the coffin, but it was the final one. Odd Obsession wouldn’t come back.

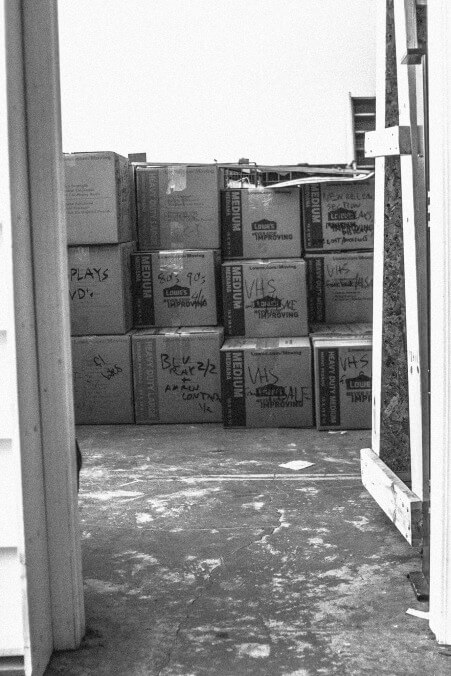

The night before the move, I came by to take a last look at the 25,000 movies that were waiting for a U-Haul to take them to indefinite storage, packed in cardboard boxes that said “Sex” or “Germany” or “H.K.” for Hong Kong. The fixtures and posters were all down, and the shelves were disassembled. You could finally see the dismal first-floor office space underneath, the dropped ceiling and blank white walls. Josh Brown, a Bronx transplant with dreadlocks who had run the store in those final years, was there. Danny P., who I hadn’t seen in a long time, dug up the old dynamite and nitramite sticks so we could take a picture.

I went inside and had a few Yorick moments that were probably too personal for a piece of writing that isn’t really about the writer. The truth is that I have two children with a woman I met in the store and that I left a lot of myself behind and that up until the store closed there were 16mm film reels on the walls and the sale bins that I didn’t realize were movies I had made when I was 19. At the risk of exceedingly obvious metaphor, I think more than a few people put themselves into the video store and maybe lived through it, too. Afterward, we dropped by Josh’s apartment. He had set aside a room for DVDs and a TV and some old Odd Obsession bric-a-brac so anyone could come and visit.

I think now of all the places that closed long before the video store, like the dive bar we all used to go to with the Polish jukebox that made me fall in love with Czesław Niemen’s “Dziwny Jest Ten Świat.” I’m thinking of city fixtures that seemed eternal but weren’t, like Jazz Record Mart, and of various stores, restaurants, and hangouts with dim lighting, distinct smells, and weird hours. A few were probably like the video store in that they were tenuous money-making ventures held together by social fabric. If they weren’t already shuttered, they would have definitely gone out of business under present circumstances.

A lot of these were also vestiges of what seemed like a weirder, fragile America or of some kind of teenage ambition that had survived into adulthood. They were places for old people, young people who didn’t have money, and lonely fanatics. They were places where you met people even stranger than yourself—places that you showed off to visiting family members or out-of-town guests. That these places disappear is a natural part of the life cycle of cities and communities, which are never what they used to be; that they won’t survive the current situation is just a fact. The point here is that when this is all over, we still have to consider what happens when we emerge into a world after an unprecedented evacuation of social space.

The big machinery will be fine, because it’s efficient and convenient and because we like it. I’d wager that a lot of middle-class-ish people are currently having the purest consumer experiences of their lives. I know I am. But those moments when reality doesn’t make you feel like you’re alone and crazy, those things we treasure in our surroundings, or those places that unexpectedly wind their way into our lives because they make our fascinations so tangible that we can touch them are all somewhere else. To be honest, I think everyone who was ever a part of the video store knew it was going to end, even from the beginning. I think that’s why many of us were there, at least subconsciously: to be the last video store clerks on Earth, renting the last copy of The Ebola Syndrome to the last person who will tell you that they thought it sucked.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.