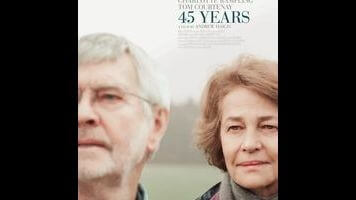

The devastating 45 Years is as much a ghost story as a marriage drama

Looked at one way, the most significant character in 45 Years hasn’t a single line of dialogue, appears only in still photographs, and died a half-century before the events of the film. Her name is Katya, and she was young and beautiful when she plummeted to her demise in the Swiss Alps. Geoff (Tom Courtenay), the man she was with when she fell, hasn’t mentioned her since he married Kate (Charlotte Rampling), his wife of four-and-a-half decades, not long after the tragedy. But mere minutes into the film, a letter arrives, like an intruder from the past: a body has been discovered, perfectly preserved in the ice. And for the 90 minutes that follow, Geoff and Kate will do little else but talk about or around Katya. She is the elephant in every room of their cozy Norfolk home.

This is not the average domestic drama. Movies about marriage can be bitter and/or perceptive, but it’s rare to stumble upon one that presents a situation as complicated as Geoff and Kate’s, where what appears to have been a long, fulfilling relationship is reframed by uncomfortable new information. A small film of big insights, heavy on dialogue but light on speeches, 45 Years often seems closer in spirit to a ghost story: Nothing goes “boo” or rearranges the furniture, but there’s a unmissable sense that we’re watching two people haunted by a specter from another lifetime.

As the film begins, Geoff and Kate are planning a big party for their wedding anniversary. From a distance, and perhaps to their friends, they seem to fit the profile of the archetypal old married couple, comfortable with each other’s flaws and tangled in each other’s habits. 45 Years immediately and skillfully establishes the pair’s peaceful, august-years lifestyle—walks to town and through nature, doting on the dog—while also immediately destroying that illusion of total contentment with the arrival of the letter. Building to the impending celebration, 45 Years counts off days of the week, not unlike a more literal ghost story, The Shining. Over this brief time frame, Geoff will become more and more withdrawn, disappearing into his memories. Kate, meanwhile, does what the heroine of any actual spectral mystery does: She begins poking around in the past, discovering not just the traits she shares with the woman she effectively “replaced,” but also the numerous hints of said woman’s presence throughout their home.

Writer-director Andrew Haigh, whose Weekend was a sharp portrait of young love, exhibits a wise-beyond-his-years understanding of the way relationships are constantly in flux, even late into their lifespans. He also reminds that marriages, including those rock-solid enough to last for almost a half-century, are between two separate people, each with their own interior worlds. How well can anyone really know anyone else? There’s a scene of Kate slipping into the attic, where Geoff has been retreating in the late hours, and discovering something shocking in the old photos of Katya: Not just a secret, but an alternate course of history, staring back at her.

Hiring veteran performers to play a couple is always a pretty good way to create a sense of a shared past for the audience. (See also: Amour.) But Courtenay and Rampling do a lot more than simply lean on viewers’ potential familiarity with their screen presences; with only a scant few details about their long lives together, the two sketch a whole history of cohabitation—a rapport forged over the decades—through a relatively slim number of scenes. Courtenay, of applicable Billy Liar fame, offers a phantom impression of the decent husband Geoff surely was, even as he’s already begun to drift away from Kate and into his past from the first moment he appears on screen. And Rampling, in what may be the greatest performance of a great career, takes us through every step of a slow-motion rude awakening, a journey from domestic contentment to full, awful understanding. Just watch what she does with her eyes and hands in this film. She can be shattering with the smallest of gestures.

45 Years is based on “In Another Country,” a short story by David Constantine, and it borrows not just a premise and passages of sharp dialogue from its source material, but also the barbed efficiency of the short-fiction format: At a spare 95 minutes, this is a film of no wasted scenes or unnecessary subplots, stripped down to something tough and focused and vivid. Yet the anniversary-party angle is all Haigh’s invention, and he uses it to devise a phenomenal new ending, one that—like the jaw-dropping finale of this year’s Phoenix—draws its power from close attention to behavior and minute shifts in body language. At the center of it is Rampling, all eyes on her, showing us everything that’s going through this woman’s mind. But even when it’s just her in the frame, when the camera has come in for a close up, there’s someone else there just out of view—the invisible third party of her marriage, the ghost over her shoulder. She’s still there. She always has been.