The director of Jesus’ Son makes a pointless arthouse exercise with The Rehearsal

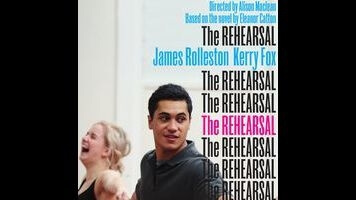

The Rehearsal, director Alison Maclean’s first feature since the 1999 Denis Johnson adaptation Jesus’ Son, is such a hodgepodge of arthouse references, arch distancing effects, and emotionally vacant wide-screen compositions that one could easily mistake it for an awkward debut film. James Rolleston stars as Stanley, a hunky first-year student at a prestigious New Zealand acting school who is encouraged by the combative, guru-like head instructor, Hannah (Kerry Fox), to develop a theater piece based on a local sex scandal that has engulfed the family of his underage girlfriend, Isolde (Ella Edward). Contrived as it may sound, this isn’t a bad premise. But every bit of inherent tension is dissipated by Maclean’s direction, which meanders from affectlessness to affectation, producing a blank mise en scène in which nothing behind or around the actors means anything, unless it literally says “Brecht” in big letters. The Rehearsal signifies and quotes conflicts and uncomfortable psychosexual pressures without ever actually delving into them, and in the process—for this is a film that’s loudly about “the process”—loses its grasp on the caustic equation of art and predatory behavior that one suspects is supposed to be its whole point.

What it has going for it are a few lengthy, impassively angular scenes of acting exercises and discussions led by Hannah at the drama school, ominously referred to only as “the Institute”; it’s in these sequences that the younger members of the cast are at their most believable, though it’s unclear whether this is an intentional ironic subtext or just unevenness. That’s true of a lot in The Rehearsal. Adapted by Maclean and Emily Perkins—the Kiwi novelist, not the star of Ginger Snaps—from a novel by Elizabeth Catton, the film moves in inelegant and aimless lurches, from rehearsal spaces and parties to stoned discussions of better movies and cutesy shots of actors goofing around in front of a pink wall. In other words, it puts itself in the unenviable spot of being too artificial for any of its meta-teen-soap plotting to seem real, while lacking the rigor that could give its artificiality context. Hannah is depicted as irresponsible and immature, while Stanley is an actor of very limited talent and emotional range, and while there’s something ballsy in centering a story about the supposedly empathetic art of Method characterization on two off-putting characters who come across as potential sociopaths, this turns out to be just one of the many suggestive ideas wasted by The Rehearsal.

The same goes for any similarities in the relationship between Stanley and George Saladin (Erroll Shand), the tennis coach caught having sex with Isolde’s 15-year-old sister, Victoria (Rachel Roberts). In Catton’s novel, the Saladin character was a music teacher, and while the change opens up all kinds of potential parallels between art and athletics and their shared obsessions with talent and training, no, it’s just an excuse for Maclean to show acting students whipping tennis rackets while making more oblique references to the mid-1960s films of Jean-Luc Godard. The Rehearsal’s dull blocking never matches its largely European influences (much of cinematographer Andrew Commis’ camerawork can be described as “attempted Haneke”), but while one might say that the movie is only asking for trouble by openly courting comparisons to acknowledged masters, The Rehearsal at least has the wisdom to include scenes of the project put together by Stanley and his fellow acting students, which is bad and artless enough to periodically remind the viewer that they could be watching something much worse.