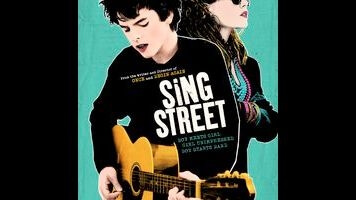

The director of Once returns to his ’80s-rock youth with the earnest Sing Street

John Carney’s peppy flashback musical Sing Street is to his earlier Once what a glossy major-label debut is to a scrappier first album: Both have their pleasures, but the former can’t help but look a little artificial when compared to the latter. To be fair, Carney already made his leap to the majors with Begin Again, a cloying NYC music drama that had the gall to sell drippy, generic Starbucks rock as some sort of “authentic” answer to the phoniness of Top 40. Sing Street, a much more winning crowd-pleaser, takes Carney back to Ireland, back to handheld camerawork, and back to his own past as a moony, pop-loving youth. If it doesn’t quite return him to the aching intimacy of Once, it at least finds a better way for him to begin again. In Sing Street, Carney harbors no delusions about the integrity or ambitions of his hero. The kid just wants to get girls.

Or one girl, anyway. To hear this autobiographical passion project tell it, there’s no better reason to pick up a microphone and start a band than to impress someone way out of your league. (Surely, plenty of world-famous musicians could link their own origin story to a similar goal.) Carney’s proxy is Conrad (Ferdia Walsh-Peelo), earnestly 14 in the Dublin of 1985. Conrad has it rough: His parents (Aidan Gillen and Maria Doyle Kennedy) are on the verge of separation, and the family’s money problems have necessitated a transfer from gentler prep school to the rough-and-tumble classrooms of Synge Street, where the kids bully, the teachers drink, and the principal (Don Wycherley) is an authoritarian Catholic prick—plus, as one scene rather casually implies, a possible pedophile.

All of that ceases to matter much, though, when Conrad catches his first glimpse of Raphina (Lucy Boynton), the teenage model who hangs out in the neighborhood, radiantly aloof in hoop earrings and hairspray. Carney shoots the big meet-cute on the steps of an apartment building, Raphina towering over Conrad, as she requests a few lines of “Take On Me.” In their next encounter, she’s seated at the bottom of the stairs and he’s the one looming large, pumped up by the confidence of the band he’s suddenly fronting. Sing Street makes Sing Street, the kids’ band, a ragtag ensemble of quick studies: Together with dorky, rabbit-loving multi-instrumentalist Eamon (Mark McKenna), pint-sized “manager” Darren (Ben Carolan), and a few other eager classmates, Conrad learns to mimic the sounds (and fashions) of the day. He gets his tips from his college-dropout brother Brendan (Jack Reynor), absorbing tastes and insights like a sponge. And he woos Raphina by putting her front and center in their amateur music videos, which get better at roughly the same rate as their songs.

The fun of Sing Street, set during a big boom period for U.K. rock, is that it allows Carney’s fond, romanticized memories of his glory days to double as a musical history lesson: Conrad, true to his rapidly evolving sensibilities, keeps passing from one phase to another, his band transforming from a Duran Duran clone to a Hall & Oates tribute to a wannabe The Cure. The music, by hitmaker and Danny Wilson frontman Gary Clark, manages the impressive feat of infectiously evoking those giants of the MTV age without sounding too accomplished. As it eventually becomes clear, we’re seeing a very familiar creative genesis, as Conrad skillfully apes his influences, like most young artists do, until a distinct style begins to emerge. (Never mind that the less plagiaristic songs, unveiled during the inevitable big-show climax, sound like they belong more in the Songs Of Innocence era than the heyday of Boy.)

Unfortunately, Sing Street proves much more appealing as a making-the-band story than a coming-of-age one. Whenever Carney’s shooting all-instrument performances or closed-door songwriting sessions, his film comes alive; there’s maybe no filmmaker working today better at capturing the joy of a rehearsal space, to say nothing of the wish-fulfillment swell he brings to a late, Back To The Future-inspired fantasy sequence. The romance isn’t so distinctive, however. Raphina, the troubled model with the older boyfriend (“See you in the future, lad,” he tells Conrad, making the boy feel very much like a boy), never stops looking like a crush object, even as she lets down some of her cool-kid defenses. That could be a byproduct of the film’s real-life roots: Carney views this dream girl through the smoky lens of a mostly one-sided infatuation—the same way, perhaps, that he looked at her living-and-breathing inspiration. Raphina is idolized even in her “flaws,” and that makes the film’s fairy-tale courtship seem a little canned, however it aligns with Carney’s own experiences.

If anything in Sing Street feels truly personal, it’s the sibling relationship: Ending with a dedication to all big brothers, the film turns Brendan into the stealth heart of the story—a deadbeat rock sage, doling out life advice and tastemaker guidance, like Lester Bangs as played by a young Seth Rogen. (Seriously, the on-the-rise Reynor bears an uncanny resemblance to the Knocked Up star.) At the same time, the character copes with a disappointment—the sting of unfulfilled potential, of bigger dreams not chased—that a breezy confection like this doesn’t quite know what to do with. To torture another musical analogy, Sing Street is like an agreeably sweet radio anthem, the song of the summer a few weeks ahead of schedule. It just doesn’t feel as built to last as Once, whose simple resonance could provoke a lifetime of “play your old stuff” requests.