The director of Pulse leads an invasion of the body snatchers in the goofy-creepy Before We Vanish

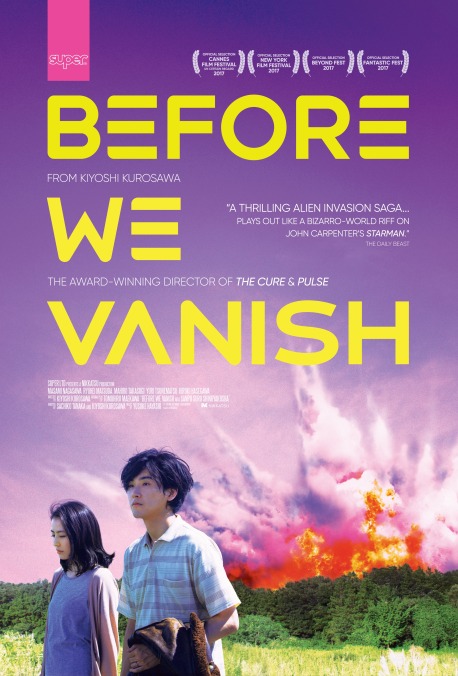

One of Japan’s premier gooseflesh provokers, Kiyoshi Kurosawa made an international name for himself in horror, specifically with 2001’s technophobic, ghost-in-the-machine creepfest Pulse. But he’s no genre monogamist; the director has applied his command of unnerving atmosphere—that ability to get skin crawling with nothing but the extended duration of a carefully framed shot—to everything from family dramas to crime procedurals to sci-fi mind-benders. With Before We Vanish, Kurosawa puts his unmistakable stamp on a paranoid pulp premise straight out of the 1950s: a post-millennial Invasion Of The Body Snatchers about alien interlopers on a reconnaissance mission. Though faithfully adapted from a stage play by Tomohiro Maekawa, the material recalls any number of space-invader classics (including the 1987 alien-buddy-cop potboiler The Hidden). Such B-movie familiarity turns out to be a liberation, not a liability; it unleashes Kurosawa’s more playful side—his comic instincts and a largely concealed flair for action-movie pyrotechnics, albeit of the budget variety.

Even at a less-than-economical two hours and change, Before We Vanish wastes little time on setup. It takes only a few minutes to realize that we’ve been dropped into an invasion already in progress, as three extraterrestrial scouts—all disguised as the humans whose bodies and memories they’ve hijacked—lay the groundwork for a full-scale planetary takeover. Two of the incognito aliens exhibit nothing but pitiless curiosity, one (Yuri Tsunematsu) trashing her first couple hosts like a teenager on a joyride, the other (Mahiro Takasugi) commandeering the van and expertise of a human “guide,” journalist Sakurai (Hiroki Hasegawa), who goes through a full range of responses to his predicament, moving from disbelief to alarm to an acquiescence bordering on Stockholm syndrome. The third imposter, meanwhile, develops a more complicated relationship with Narumi (Masami Nagasawa), the Earth architect whose unfaithful, estranged husband (Ryûhei Matsuda) he’s possessed. Their scenes together are a miniature Starman, melodramatically linking the survival of the species to an interplanetary, girl-meets-E.T. quasi-romance.

Some of Before We Vanish plays to Kurosawa’s existential-dread wheelhouse. The aliens are essentially on a fact-finding operation, and they collect information on the population they’ll soon be colonizing by tapping people on their foreheads to steal their “conceptions,” a.k.a. their grasp of key abstract notions, like “property” or “self.” One scene, simultaneously disquieting and funny, finds Narumi’s condescending creep of a boss losing the very idea of work—a mental heist that leaves him in a desperate infantile state, running around the office throwing paper airplanes and smashing his subordinate’s projects. But speaking of conceptions there for the plucking: Like most Body Snatchers glosses, official and unofficial, Before We Vanish locates deeper subtext in its identity-related anxieties. The film is set near an American military base in Japan (“U.S. Army get out” reads some briefly glimpsed graffiti), and it’s possible to interpret the narrative as an occupation parable. Who really are these alien invaders, treating a foreign land they don’t understand as their destructible playground, while threatening key cultural values like family and work ethic?

Kurosawa’s best films—the chilling policier Cure, the devastating domestic drama Tokyo Sonata—are slow burns, privileging the enveloping mood of a nightmare over traditional genre thrills. He’s the kind of master of suspense who uses stasis to instill unease, planting his camera for long takes that hold so long that they trigger an irrational shudder, a danger sense. Before We Vanish is a goofier but more dynamic affair: a fast-paced science-fiction pastiche, caught somewhere between Atomic Age camp and J-horror creepiness. It has gunfights, fistfights, explosions, multi-car pileups, a crosscutting race-against-the-clock story, a cornball soap climax, and a final action scene that riffs on the crop-dusting centerpiece of North By Northwest. It also boasts effects that alternate between resourcefully suggestive (blinking lights outside a window to imply the arrival of a UFO fleet) and downright cheesy (though even the bad CGI has a certain throwback appeal). But Kurosawa still directs with a master’s control and calculation, and the theatrical origins of the material keep the focus on the half-comic, half-unsettling interactions between the human characters and their befuddled, jovial imitators. It’s minor pleasures from a major talent: B-movie fun in the key of Kurosawa.