Rodney Ascher is a scholar of obsession, and sometimes a conduit for crackpots. Each of his documentaries is a peek into overactive imaginations, allowing subjects to hold court on whatever haunts their dreams, literally or otherwise. To enjoy these plunges down the rabbit hole of the racing human mind requires a fascination

fascination. Ascher’s first feature, the absorbing cult-of-Kubrick essay film

, seemed to tick off plenty of folks who mistook its presentation of variably persuasive interpretations of

as some sort of concurrence with each of them. Or maybe the detractors just felt that even airing those wild takes was a waste of time. Certainly, there will be those who feel the same, and probably more strongly still, about Ascher’s new movie,

, which focuses on a conspiracy theory that’s grown steadily in popularity over the last couple decades: the belief that we’re all living not in a physical world but in a computer simulation of the same.

Early into the film, Ascher cuts to footage from 1977, when Philip K. Dick, the almost premonitory sci-fi guru whose stories inspired Blade Runner and Total Recall, stepped to a podium at a convention to reveal his conviction that reality as we perceive may not be reality at all. That’s a notion much older than Dick’s influential mindbenders, and older than computers, too; as one talking head points out, it goes back to at least Plato. But Dick’s paranoid remarks, which form a kind of rhetorical backbone (Ascher returns to his speech throughout the film), floated much of the fundamentals of what we now call simulation theory—an idea that gained lots of new followers with the release of The Matrix in 1999, the publishing of Nick Bostrom’s seminal essay “Are We Living In A Computer Simulation?” in 2003, and the propagation of it as a legitimate possibility by the likes of Elon Musk and Neil deGrasse Tyson.

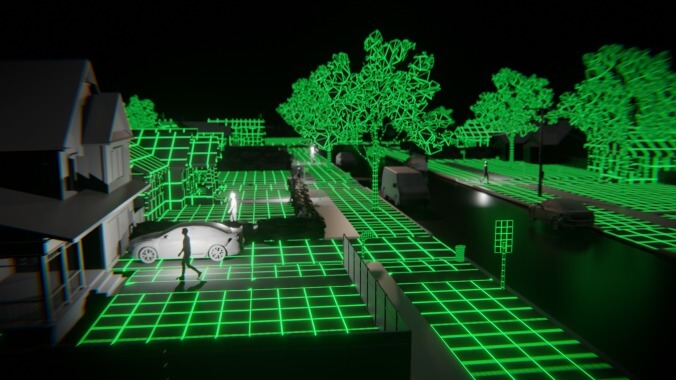

A Glitch In The Matrix unfolds as a flood of exposition and conjecture, accompanied by a gaudy infotainment montage of video-game footage, movie excerpts, and computer-animated recreations. On its chosen subject, the film is not comprehensive: That there’s no mention of, for example, the supposed “glitches” (like Trump’s unlikely victory) that have fueled proponents of the theory of late, nor the news that billionaires have funded scientific campaigns to free us all of our artificial construct, betrays more psychological than journalistic interest. As usual, Ascher assembles a brain trust of true believers to discuss what might charitably be described as their mutual preoccupation, less charitably their shared delusion. These four “eyewitnesses,” as the film labels them, speak from behind elaborate digital avatars, possibly to disguise their identities (one confesses that he’s a teacher, a job one assumes might be jeopardized by the revelation that he holds this particular belief) or perhaps just for visual-conceptual consistency. That each ends up looking a little silly, expounding straight-faced theories in cartoon video-game form, is one of those little details that helps underscore that—in social-media parlance—Ascher’s retweets are not necessarily endorsements.

Ideas are infectious. Ascher conveyed as much in his last documentary, The Nightmare, which explored the phenomenon of sleep paralysis as a prime example of the war our brains wage against us. (At the film’s Sundance midnight premiere a few years ago, you could feel the whole auditorium shift uncomfortably in their seats when one interviewee disclosed that the frightening condition could be “contracted” through suggestion—that people have actually experienced sleep paralysis after learning about it!) For as slyly amusing as A Glitch In The Matrix can be as a portrait of collective hair-brained hypothesizing, the film acknowledges the potential danger of buying into such a philosophy. If nothing’s real, what’s to ethically stop you from mowing down your neighbors? To that end, the film’s most disquieting sequence throws audio of convicted murderer Joshua Cooke, who pleaded the so-called Matrix Defense in court, recounting the killing of his parents over a kind of first-person shooter tour of his house, digitally recreated. It seems intended as a cautionary tale, but offering Cooke this platform at all isn’t in the best of taste.

If none of this is as gripping as Ascher’s past investigations into the labyrinth of the mind, it’s largely because the filmmaker is this time doing more summarizing than probing. Room 237 and The Nightmare opened portals into the personal headspace of their subjects, into their torments and interpretative gymnastics, the horror movies created by or imprinted upon their brains. The ideas tossed around in Glitch have been widely disseminated: A quick Google search reveals dozens of articles, all with essentially the same headline, that go into this outlandish postulation in greater detail. Exhaustive or not, the film sometimes plays like little more than a fast-paced primer on the basics of simulation theory. Even when Ascher hits The Matrix itself, the readings are all textual and surface level; one misses the way he turned The Overlook inside out, using the big reaches of his armchair analysts as a blueprint.

Simulation theory sounds like a nightmare, but it’s more of a daydream—a fantasy that every moment in life that seems unfair or inscrutable is just a flaw in the algorithm, not proof that the universe abides by no algorithm. That’s the USB chord that connects A Glitch In The Matrix to Ascher’s past work: Just as Room 237 was less about The Shining than the meaning we seek in every crevice of the pop-culture we love, this film uses simulation theory as a window into the desperately human search for order and logic, with technology as just another variant on some grand designer outside the membrane of our consciousness. Here and there, Ascher’s committee of talking heads reveals a flicker of self-awareness, and you wonder if this is what the filmmaker was after all along. One of them, for example, briefly muses about how it makes sense that he struggles to connect with other people, given that the world everyone occupies is just a big, phony cluster of code. Is it any wonder that he doesn’t follow that cursor of thought to a scarier, more logical conclusion?

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)