Dresden, in the mid-1930s. A precocious little boy and his beautiful young aunt follow a tour through an exhibit of “degenerate” artworks, taking in the paintings of Otto Dix and Wassily Kandinsky while their tour guide blathers on about the common man, real art in the Reich, and the like. Nazism is the status quo, but the boy’s reality still seems nostalgically innocent, the museum outing capped off by one of those pseudo-magical movie moments in which the aunt talks a depot of bus drivers into honking their horns in unison, like a tuning orchestra, while the camera circles her for infinite degrees. But the grown-up world is slipping into madness, beginning with the aunt herself; pretty soon, she’s standing naked in the living room, banging a glass candy bowl against her head as she declares, “I’m playing a concert for the Führer!” Off she goes to the loony bin and eventual death, and the country follows, the war years unspooling in a montage: uncles killed on the Eastern Front, neighbors killed by the Allied firebombing of Dresden, a hand with a skull ring turning a gas nozzle.

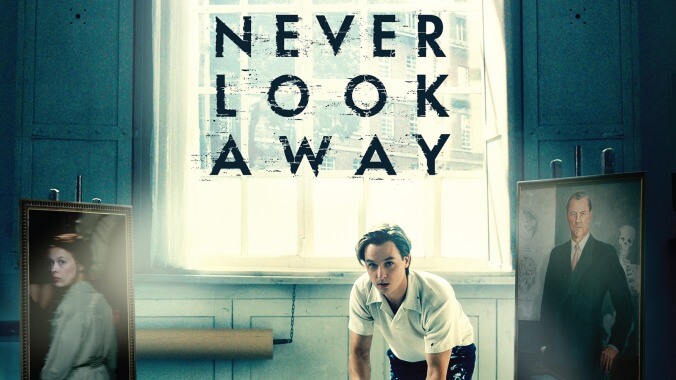

We follow the boy, Kurt Barnert, as he grows up into a young man (Tom Schilling) in East Germany. He becomes an art student and bucks against the conventions of Soviet-style ’50s socialist realism; falls in love with an aspiring fashion designer and marries her, despite the machinations of her father, the villainous Nazi gynecologist Professor Seeband (Sebastian Koch), who played no small role in the beloved aunt’s demise; escapes to West Germany and bucks against the conventions of ’60s conceptual art. The Germans invented this genre: the bildungsroman, the story of the inner development of a restless young protagonist, typically male. Running at a miniseries pace, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s Oscar-nominated Never Look Away stretches this template into 188 minutes of historical ironies, sex scenes, soap-operatic twists of fate, and rib-elbowing asides about art-school pretensions on both sides of the Cold War divide—enough to make one think that, man, if this thing had any style, it might seem really self-indulgent.

But whatever liberties Never Look Away extends to artists—to experiment, to challenge, to find one’s own cryptic meanings—it does not apply to itself. Henckel von Donnersmarck’s 2007 debut, The Lives Of Others, had an emotionally compelling conflict and high stakes, but his return to both the Cold War setting and German-language film is mostly kept together by his stolid, unsurprising direction. Kurt’s art and biography are loosely based on the early life of Gerhard Richter, and his mentor, Antonius van Verten (Oliver Masucci), an eccentric performance artist who is never seen without his fly-fishing vest and fedora, is Joseph Beuys in everything but name. Henckel von Donnersmarck even gives him Beuys’ extraordinary purported backstory—though, in keeping with the film’s sentimental streak, he presents it to us as fact, rather than an artist’s self-invented myth.

Never Look Away’s focus on trial-and-error creative frustration makes it a tad more sophisticated than the average drama about budding artists in search of higher truth, though it seems to be at a loss as to how to fit Kurt’s irredeemable, despotic ex-SS father-in-law and his attempts to evade prosecution for war crimes into the mix. One can see how, in theory, this anticlimactic subplot could represent the way Kurt’s nominally apolitical art subconsciously addresses the guilty conscience of the Nazi past, for which Seeband is a despotic stand-in. But mostly, it drags and falls back on the cheapest, least insightful explanations for art: That it is a form of autobiography. We watch as the film moves from year to year, the characters sometimes disappearing illogically, with Kurt forever at work on one unsatisfying project or another, until he finally finds a subject that speaks only to him. The movie’s German title—Werk Ohne Autor, which means Work Without Author—seems almost too apt.