The director of The Lobster trades humor for horror in the nightmarish Killing Of A Sacred Deer

The first thing we see and can never unsee in The Killing Of A Sacred Deer is a gaping chest cavity: flesh and bone parted to expose the organ inside, pumping frantically away in extreme close-up. To open with open-heart surgery sends an awfully clear message: Abandon all hope/concern that Yorgos Lanthimos, the now two-time Oscar nominee (!) behind such deranged provocations as Dogtooth and The Lobster, might start softening his blows. Of course, there’s more to glean from that undulating mass of veins and tissue than a warning for the squeamish. Maybe it’s a microcosm for the whole movie, which pounds and throbs with constant dread. And remember what hideous beating signified for Edgar Allan Poe? Nothing primes the ventricles of a telltale heart like suffocating guilt.

The man tinkering with the ticker is Dr. Steven Murphy, renowned cardiologist. He’s played by Colin Farrell, burying his movie-star swagger even deeper under a deadpan glaze—and, in this case, a bushy beard—than he did in The Lobster. Steven has it all: a great job; a nice house in a nice part of town; and a loving wife, Anna (Farrell’s Beguiled costar Nicole Kidman), and two bright kids, teenage Kim (Raffey Cassidy) and preteen Bob (Sunny Suljic). If there’s one tiny wrinkle in his perfect suburban life, it’s the secret appointment he keeps—a regular rendezvous with a high school kid, Martin (Barry Keoghan), at a local diner, where the two meet for purposes unclear.

It takes a while for Lanthimos to clarify the nature of this relationship, but the encounters feel vaguely… off from the start. Maybe it’s the eerie, persistent whine of violin, teasing a darker subtext to the pleasantries. It could also be that there’s something not quite right about Martin himself. Keoghan, who had a small but significant role in this summer’s Dunkirk, shifts low-key politeness a few notches left of normal; he has the kind of creepy thousand-yard calm that you see in mug shots after a mass murder, neighbors prattling on about what a “nice boy” the culprit always seemed. Martin will persistently insinuate himself into Steven’s life. But like a vampire, he has to be invited first. What could the boy have on the man that would convince him to open his doors? Everyone admires Steven’s hands, but they’re not as clean as they look.

Unfolding with the inevitability of a bad dream, The Killing Of A Sacred Deer is Lanthimos’ darkly intense, almost biblical spin on one of those thrillers about a yuppie family terrorized by a vengeful stalker. It’s like Cape Fear by way of The Shining, just in the same absurdist register as all of the Greek director’s trips to the Twilight Zone. To say where the plot goes would be unfair, but it involves a mysterious malady, an impossible choice, and a terrible reckoning. Those up on their Greek tragedy may recognize the outline of Iphigenia’s tussle with Artemis—a dispute that began, hint hint, with a slain deer. But you needn’t know for mythology to recognize a false deity, courting comeuppance by deciding who lives and who dies. Can it be an accident that when the good doctor sits down to watch Groundhog Day with Martin and his mother (Alicia Silverstone), in some sort of twisted matchmaking scheme, all we hear is Andie MacDowell telling Bill Murray that he’s no god? Steven relishes his power, inside and outside the operating theater; when Anna wants to initiate sex, she undresses and lies motionless on her back, like a patient awaiting surgery.

One does have to wonder if Lanthimos should have played this scenario a touch straighter. As always, his characters deliver dialogue with an almost lobotomized formality—the stilted speech pattern that’s become the filmmaker’s signature, here suggesting aliens doing an unconvincing imitation of upper-middle-class American manners. This is, on a whole, one of the director’s least comic creations—it’s much closer to horror than humor—but there are still traces of droll lunacy, like the daughter warbling out a robotic rendition of Ellie Goulding’s “Burn.” Were the film set in the real world, as opposed to Lanthimos Land, the contrast between the family’s sheltered privilege and the surreal ordeal it’s plunged into would be more extreme. Of the actors, only Kidman seems to have her feet firmly planted in both stylized affectation and real feeling. She fits perfectly within the film’s gallery of Lanthimosian pod people, while still evincing genuine rage, fear, and frustration as her cozy life unravels.

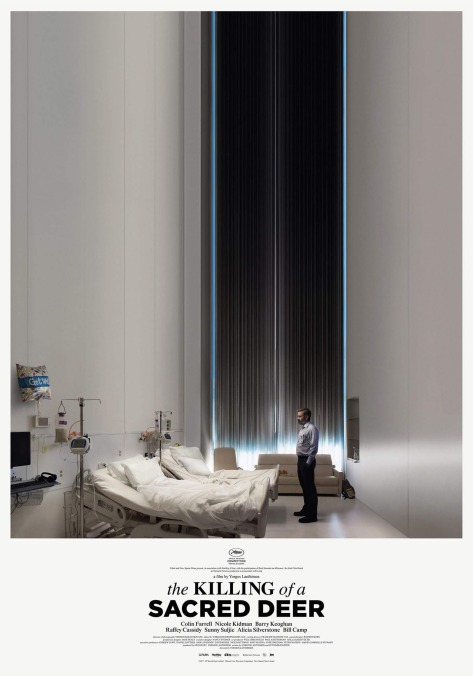

None of Lanthimos’ movies can be taken strictly at face value; they’re all about more than just their crooked internal logic. The Killing Of A Sacred Deer doesn’t have as sharp an allegorical edge as his best work—it’s no Dogtooth in that respect—but it does find the director honing his command of unnerving atmosphere to a razor point, enhanced by a camera that glides menacingly down hospital corridors and gazes from above with the severity of a merciless god. By the film’s apocalyptically over-the-top finale, when the chickens really come home to roost, submitting to the madness becomes more appealing than searching for method in it. “Do you understand? It’s a metaphor,” someone says at one point, in a wink to the audience. Notably, the character is explaining biting a bloody chunk out of their own arm. You don’t really have to get the metaphor. Some things, like an exposed beating heart or teeth sinking into flesh, are ghoulishly fascinating enough on the surface.