Three years ago, something rather extraordinary happened: A Holocaust drama won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. That in itself is nothing unusual, of course—when in doubt, while filling out your Oscar pool, always pick the movie involving Nazis (assuming there’s only one, that is), and you’ll rarely be wrong. What made Hungary’s Son Of Saul so remarkable is that people were more bowled over by its form than by its content, even though it takes place entirely within the Auschwitz concentration camp and closely follows a protagonist whose job, as a Sonderkommando, is to dispose of gassed corpses. Director László Nemes employed the boxy Academy ratio and severely shallow focus, combined with sophisticated sound design, to keep the horror peripheral and yet omnipresent; there was still some debate about whether it’s ever ethical or appropriate to depict such events, but even those who found Son Of Saul obscene generally conceded the visual and aural mastery of Nemes’ singular approach. He was clearly an immensely gifted filmmaker, and it was hard to imagine what he might do for an encore.

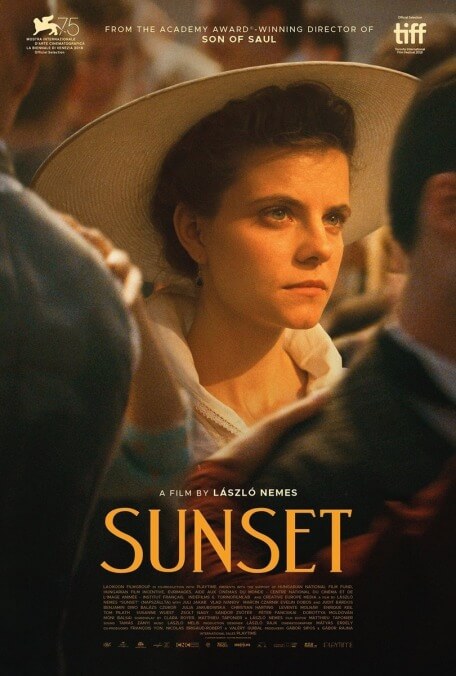

Sunset, Nemes’ second feature, not only confirms his talent but demonstrates that his style works beautifully even when transferred to perhaps the least horrifying milieu imaginable. Set in 1913 Budapest—opening text reminds us of the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s majesty at the time—this is an almost surreally tense, hypnotic movie about a young woman (Juli Jakab) applying for a job at a very fashionable hat store. There’s intrigue, naturally, and plenty of it. For one thing, the woman, asked her name, replies “Irisz Leiter,” which raises her interviewer’s eyebrows, since the shop is called Leiter’s. Turns out it had been established by her parents, who died in a fire when Irisz was 2; she’s spent most of her life cared for by strangers in a distant town, training to be a milliner, and now wants nothing more than to work for what was once her family’s business. Gently dissuaded by its current manager, Mr. Brill (Romanian star Vlad Ivanov), Irisz sticks around just long enough to hear rumors of a brother she’d never been told existed, and sets out on a quest to find him—one that grows stranger and more disturbing as it goes along.

Maybe that’s not quite right, actually. Sunset is a long picture (142 minutes), and its structure is somewhat odd; intensity steadily builds for about an hour and a half, reaching what seems like a frenzied climax… and then the film sort of starts over, making its final hour feel like a mini-sequel. There’s a solid reason for this—it corresponds to a shift in perspective, bringing the Empire’s royal family into the mix—but that rationale can’t entirely overrule a mild feeling of stagnation. Also, the film’s arresting final shot makes explicit a sociopolitical reading that was more potent when it was left implied (as in, say, the movie’s title). But these flaws become evident only after an entire normal movie’s worth of riveting magnificence. Sunset takes place over several days, and employs conventional editing, yet its feature-length initial movement (up to and including a key character’s death, or at least apparent death) somehow creates the impression of unfolding in a single real-time shot. That’s how skillfully Nemes orchestrates each individual moment, as well as the film’s overall relentless flow. Even a handful of shots that appear at first to be disconnected turn out to be, for example, Irisz’s view through a motorcar’s window, revealed as the camera pulls back.

Nemes’ choice to shoot Son Of Saul in Academy ratio seemed crucial, keeping the atrocities just out of frame. Sunset, however, employs widescreen compositions to surprisingly similar effect, sticking tight to Irisz throughout while suggesting the teeming, vaguely malevolent world through which she moves. Jakab (who also briefly appeared in Saul) has the sort of face that looks severe even in repose, and doesn’t crack a smile for nearly two-and-a-half hours; the quiet ferocity of her performance provides a necessary anchor for what becomes an enthralling exercise in free-floating anxiety. Sunset features occasional bursts of violence, and eventually alludes to a grotesque understanding between Leiter’s management and Hungary’s royals, but the film is most effective when its waking-nightmare aspect seems least explicable. The sense of something ominous lurking beneath every genteel encounter derives not from what the characters say and do (though there are some heavy silences), but from the camera’s immersive, impassive gaze. Anyone can make a Nazi death camp terrifying. A real tour de force is doing the same for a hat store.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.