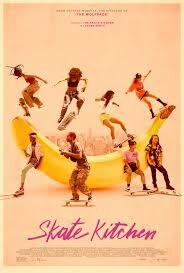

The director of The Wolfpack hangs out with the coolest girls in NYC in Skate Kitchen

If the kids are anything like Skate Kitchen, the real-life all-female New York City skate crew that inspired, shaped the direction of, and stars in The Wolfpack director Crystal Moselle’s narrative feature film debut of the same name, then they really are all right. Though concerned with stereotypical teenage-girl matters like crushes and exes, this multi-racial, pansexual group of young women’s ultimate loyalty is to each other—and to their boards. And as kids who are born and raised in New York often are, they’re also impossibly, even intimidatingly cool.

Rachelle Vinberg, a non-professional actress and member of Skate Kitchen, stars as Camille, a repressed 18-year-old living in Long Island with her unnamed, overprotective single mother (Elizabeth Rodriguez). The film opens with an in-your-face blending of skate tricks and female anatomy, as Camille sustains a rather horrifying injury colloquially known as “credit carding” where she lands vertically on her upright board, crotch first. She has to get stitches as a result, after which her mom forbids her to skateboard because “you might not be able to have kids next time.” Camille, being 18, immediately defies this rule, and as soon as her mom leaves for work she’s off to Manhattan to find out more about the Skate Kitchen crew she’s been following on Instagram. (As befits a film about teenagers in 2018, Instagram factors heavily into this story.) Soon, she’s accepted into the group, which helps her through a rough patch with her mom—that is, until a budding romance with a skater (Jaden Smith) from a rival crew threatens Camille’s bond with her friends.

Moselle—who introduced the members of Skate Kitchen to each other when she cast them in a short film for the fashion brand Miu Miu, and wrote a feature script around them after they started hanging out in real life—shoots the film’s teenage protagonists in intimate, handheld closeup, the camera lingering admiringly on their septum piercings and dyed eyebrows. She also frequently pauses for dreamy, impressionistic scenes of the girls doing tricks at the skate park, rolling down the streets of Manhattan en masse, partying, or just hanging out in one of their bedrooms, the pink wallpaper plastered with pages ripped from Thrasher magazine. Some of these take on the character of music videos, as Moselle cleverly incorporates the skritches and pops of skateboards grinding across the concrete into pop and hip-hop hits.

Moselle’s freewheeling shooting style and approach to narrative earn Skate Kitchen comparisons to Andrea Arnold’s American Honey, a less structured and conventional film about a ragged but tight-knit subculture of young people. It even has its own Shia LaBeouf in the form of Jaden Smith, one of only two professional actors in the film. (Smith isn’t nearly as creepy as LaBeouf was in that film, however, even if he is a typically self-centered teenage boy.) The makeup of Skate Kitchen itself gives the film a stronger feminist viewpoint, however, with invigorating digressions into feminist consciousness-raising, like the scene where members of the group share their experiences with harassment and sexual assault while riding the subway.

Despite all this, and perhaps because of the heavy influence its young protagonists had on guiding the story, this is not as thematically weighty of a film as Arnold’s. And it feels slighter in comparison, particularly in the romantic subplot. In fact, all the weed smoking and street-smart sidewalk banter aside, Skate Kitchen’s perspective is, in many ways, downright innocent; as such, it may be a better fit for adolescent viewers than adult ones. But its perspective, which brings some much-needed diversity to the traditionally white-male face of skateboarding, is valuable and refreshing, as is its message about female friendship. If you have a teenage girl in your life who’s into skate culture, it just might be her new favorite movie.