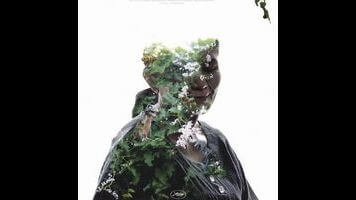

The director of Uncle Boonmee returns with a double dose of magical realism

Milky white clouds billow against a blanket of blue, the perfect canopy for a lazy afternoon. And then, from the space beyond the frame, an enormous amoeba floats into view, swimming across the sky as though it were a body of water. This bizarre non sequitur is tucked halfway into Cemetery Of Splendor, one of the two new movies by Apichatpong “Joe” Weerasethakul coming to theaters this weekend. The scene functions as a pretty handy illustration of how Joe, Thailand’s most celebrated filmmaker, gently collides the natural with the supernatural, making ghost stories look like slices of life (and vice versa). In a Weerasethakul film, characters respond to a whole season’s worth of X-Files episode fodder—shape-shifting spirits; reincarnation; corporeal possession; catfish performing cunnilingus—as matter-of-factly as they do to any other part of their laid-back rural lives. If the term “magical realism” didn’t already exist, someone would have to coin it just to accurately describe the guy’s work.

Like Joe’s decade-old Syndromes And A Century, Cemetery Of Splendor takes place predominately at a country hospital—this one formerly a school, built on the grounds of an ancient, war-torn palace. Dozing soldiers, afflicted with a strange virus that prevents them from waking up, undergo experimental light treatments; tubes of glowing primary color illuminate their sleep ward. Jenjira (Jenjira Pongpas Widner), a middle-aged housewife with a bum leg, volunteers at the hospital, mostly to inject a little excitement into her small-town life. Responding to her massage therapy, one of the soldiers, Itt (Banlop Lomnoi, from the director’s earlier Tropical Malady), stirs from his deep slumber, and the two embark on a very hesitant, chaste romance. Or at least that’s what appears to be happening; situated on the Thai equivalent of one of those cursed Indian burial grounds, the hospital has a way of blurring the lines separating conscious from unconscious thinking, reality from dreams.

Cemetery Of Splendor is notable in Joe’s oeuvre for the way it implies a distinction between the usual intrusions of otherworldly activity—the spectral guests everyone on screen seems to take in stride, like a visit from the mailman—and the hallucinatory visions that can’t necessarily be trusted. For example, there’s little doubt that the hospital’s resident medium, Keng (Jarinpattra Rueangram), really can speak to the comatose and recall her past lives. But does an encounter with two princesses, taking a flesh-and-blood break from their normal gig as the inanimate subjects of a river shrine, really happen? Joe codes almost nothing here as truly unordinary, staging the most outlandish of material with the same quiet, casual grace that he applies to the scene-setting. The deadpan comic appeal of this approach—which clashes neither with the writer-director’s melancholy character work nor his taste for more lowbrow humor, like nurses playing with a sleeping patient’s erection—is not always acknowledged, even by Weerasethakul fans.

But as much as Joe excels at this peculiar blend of the mundane and the surreal, his best movies introduce an element of danger or at least urgency. Tropical Malady, still the filmmaker’s finest hour, radically splits its narrative in two, chasing one of his signature low-key romances with its metaphoric continuation—a wild hunt through the jungle of erotic pursuit. And for as plainly as it presents the existence of a spirit world, the Cannes-winning Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives has flares of dark mystery, embodied by the red-eyed primate specters that stalk its woodland backdrop. Cemetery Of Splendor, by contrast, is almost too relaxed, breezing over its most winningly strange passages. (More of the princesses couldn’t have hurt.) All the same, the film succeeds in attuning its audience to a quieter way of life; while a construction crew tears into the land nearby, both unearthing the past and hastening the future, Joe’s characters luxuriate in tranquility. “Hunger for heaven leads to hell,” reads a sign in their backyard—and Joe, who sees as much wonder in wildlife as the afterlife, makes a case for living in the now.

Anyway, the film is more dynamic than Mekong Hotel, the slimmer and even weirder Joe project opening Friday; more of a long short than a short feature, it plays like something that should be included on the bonus disc of the Cemetery Of Splendor Blu-ray. (Both films are being distributed by Strand and start tomorrow at the IFC Center in New York.) Here’s another of Joe’s tender courtships, this one occurring at a hotel on the Mekong River, which runs between Thailand and Laos. And here, again, an element of the supernatural intrudes on the naturalism, as a young woman discovers that her mother is actually a flesh-eating ghost; that scenes of her snacking on entrails scarcely disrupt the vacation vibe is a testament to how carefully Joe modulates mood. Mekong Hotel does include a documentary component: It interrupts its fictional material with scenes of Weerasethakul himself chatting with a constantly strumming singer-songwriter type, in the same way that Cannibal Ghost Mom totally stumbles her way into the love story. For the most part, though, this hour-long curiosity feels like a fans-only doodle, riffing on motifs Joe has done better elsewhere. Even for a filmmaker who takes pride in scaling the fantastic down to everyday proportions, there’s such a thing as going too slight.