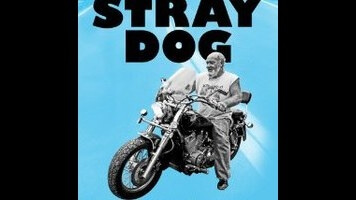

The director of Winter’s Bone goes back to the Ozarks in Stray Dog

Returning to the bottom of the Ozarks, filmmaker Debra Granik profiles Ronnie “Stray Dog” Hall, a Vietnam veteran, biker, and trailer park operator who played a rural crime boss in her last film, Winter’s Bone. With stencil-typeface credits that can’t help but bring to mind the scrappy regional genre movies of the 1970s, and an opening sequence that finds Hall sampling moonshine with his buddies, Stray Dog announces itself as something homegrown—a verité look at a quintessentially American oddball, made with an eye for life in rural Southern Missouri. This is a place of old men with beards and young men with goatees, camo and ratty baseball caps, where near everything exists in a state of perpetual DIY repair.

Barrel-chested and neighborly, Hall holds to the biker ideal of the freedom of the open road, but spends almost the entire movie trying his best to help those around him. He travels to military funerals and Vietnam memorial rallies; attempts to talk his pregnant teenage granddaughter into going to college; helps a friend pull his teeth to save money on dental bills; tries to ease his 19-year-old stepsons, twins Felipe Angel and Felipe De Jesus, into their new life in the U.S.; and tends to the residents of his trailer park, pointedly called At Ease, many of them veterans.

His voice is deep and folksy. “It ain’t like I ain’t been poor, man,” he tells a tenant who won’t be able to make rent once his unemployment checks run out. “I gotta make a living, but I ain’t gotta make it all off of one person.” In some ways, Hall is an ideal documentary subject: Eminently likable on-camera, he’s got enough life behind him that Stray Dog can sustain viewer interest just by revealing unexpected details, one scene at a time. (One throwaway moment at a cookout, for instance, reveals that he is conversational in Korean.) Hall lives in the kind of environment that produces its own disquieting poignancy, like the children’s birthday clown who knowingly nods along while listening to Hall talk to a young man who wants to join the Air Force. It produces its own heavy-handed ironies, too. A viewer can’t help but read the sinking feeling on the faces of Hall’s stepsons—young men in slim-fit shirts who’ve spent their whole lives in Mexico City—as their new neighbors, many of whom live on disability and unemployment, ask them how happy they are to finally arrive in a land of opportunity.

Hall’s struggle with PTSD, the result of two tours in Vietnam, is mentioned often, but remains largely offscreen, because Stray Dog isn’t so much a movie about trauma as it is about people trying to make meaningful lives out of whatever pieces they’ve been given. Everything seems assembled from different parts: a new floor installed by Hall and a team of fellow biker-vets in the home of a woman whose daughter died in Iraq; the way Hall and his wife, Alicia, speak a mixture of English and Spanish; Alicia’s bedroom prayer stand, with its collection of Catholic saints and yogis. The lack of tension seems to be Granik’s whole point, which isn’t always dramatically compelling—with a few stretches of the movie coming across as slow and aimless—but makes for a generous portrayal of people making do.