Robert Zemeckis, the Hollywood fabulist who made Forrest Gump and Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, remains a wizard of state-of-the-start spectacle—a filmmaker still perched, after three decades in the blockbuster trenches, on the cutting edge of motion-picture technology. At times, though, it’s hard to watch his movies and not wonder if he’s also not a bit like the hubristic scientists of Jurassic Park, that cautionary tale from our other maestro of CGI enchantment. To paraphrase Ian Malcolm himself: Is Zemeckis too preoccupied with whether he can do something to stop and think about whether he should? The question looms, certainly, over his detours into motion-capture animation, featuring dead-eyed digital pod people with the voices of movie stars. And it’s worth asking, again, in the face of his frankly disastrous new film, Welcome To Marwen, in which the director takes a fascinating true story of recovery through creative expression and drags it across a sticky-saccharine stretch of the uncanny valley. It’s the weirdest film of his career. One of the worst, too.

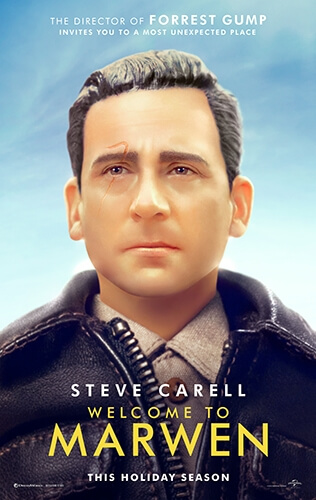

Zemeckis’ last picture, the throwback espionage thriller Allied, transported audiences to a lovingly, meticulously crafted recreation of Europe circa the second world war. That’s true, in a sense, of Welcome To Marwen, too. The eponymous setting is an imaginary 1940s Belgian town, constructed to 1/6th scale in the Kingston backyard of Mark Hogancamp (Steve Carell). Mark, as the script by Zemeckis and Caroline Thompson reveals through clumsy exposition, is grappling with some serious demons. Emotionally and physically, he hasn’t recovered from the savage beating he received outside of a bar, which left him with huge chunks of his memory missing and enough nerve damage to make drawing—his passion and livelihood—impossible. To cope with the trauma of the attack, Mark has built Marwen, a literal safe space, populated by tiny plastic avatars of the women in his life, Nazi villains modeled on his assailants, and a roguish fighter-pilot version of himself, confident and hard-boiled.

It’s not impossible to imagine a compelling movie on this subject, because one already exists: Marwencol, Jeff Malmberg’s documentary on the real Hogancamp, who’s since become a celebrated artist with exhibitions and a published collection of his photos. This isn’t, of course, the first time that Zemeckis has extravagantly remade a nonfiction film—The Walk, about Philippe Petit’s famous tightrope act between the Twin Towers, covered the same events as Man On Wire. That story, though, lent itself naturally to a high-tech dramatization. There’s no sensible rationale for the effects-heavy approach the director takes with Welcome To Marwen, nearly half of which actually takes place within the titular town, as Hogancamp’s inanimate surrogate springs to life, Toy Story-style, to act out the pulpy WWII melodrama that the actual Mark told through simple, strikingly composed still images. Zemeckis envisions the characters—buxom stand-ins for his female friends and acquaintances, including his rehab therapist (Janelle Monáe) and the local hobby-shop owner (Merritt Wever)—as Barbie dolls with expressive features. They’re every bit as creepy as the waxy Tom Hanks ensemble of The Polar Express.

Tacky and interminable though these flights of fancy may be (one scene, of Mark’s babe militia gunning down some Nazi torturers, is set to “Addicted To Love”), they’re arguably preferable to the mawkish recovery drama Welcome To Marwen otherwise offers. Carell can be an understated and sympathetic dramatic actor, but here he’s stuck playing a cloying, childlike caricature of damaged genius—the kind of role Robin Williams, rest his soul, might have mugged his way through in the late ’90s. It doesn’t help that the film saddles the former Office star with a few unintentionally hilarious screaming jags (accidental shades of Michael Scott’s over-the-top tantrums), nor that his potential romance with a neighbor (Leslie Mann) mostly just asks the love interest to marvel—with polite curiosity and endless patience—at her new admirer’s eccentricities. As in this year’s similarly maudlin (and misjudged) 22 July, the climax hinges on whether our hero can gather the strength to face his attackers in the courtroom. He faces them regularly in Marwen, of course, though the fantasy world’s real villain is a fickle, metaphorically significant witch (Diane Kruger) who can blip characters from existence with the flick of her wrist.

The men who beat Hogancamp within an inch of his life did so after he confessed to them that he liked wearing women’s shoes. To its credit, Welcome To Marwen treats that aspect of the man’s personal life respectfully and matter-of-factly (plenty of Hollywood versions of this story might have omitted it entirely), though Zemeckis does seem a little squeamish about Mark’s sexual kinks, to say nothing of his unwillingness to really interrogate the artist’s habit of turning every woman he knows into a literal plaything within his elaborate backyard installation. Still, all of that is less reductively handled than Hogancamp’s struggle with PTSD, which Welcome To Marwen depicts, basically, as psychotic episodes—actual fissures in reality, as Mark’s toy soldiers invade his real life. Marwencol asked tough questions about using art as therapy, pondering whether grappling with trauma in a controlled environment, like Marwen, might eventually become an excuse to not truly confront it. But in turning Hogancamp into a gently disturbed misfit who lapses involuntarily into fantasy, Zemeckis actively cheapens and simplifies his process. Certainly, the filmmaker shows little interest in his subject’s actual talents, including his eye for composition and his almost cinematic storytelling.

Long before the arrival of a blatant Back To The Future reference, it’s clear that all of this could be quite personal for Zemeckis, who’s spent a career disappearing into his own fantasy worlds. Is there a meta dimension, an interesting auto-critique, in the CGI passages, which acknowledge—intentionally or not—how peculiar and off-putting it can be to turn real people into lifelike automatons? Undeniably an auteur work, Welcome To Marwen is bonkers and confessional enough to earn it a fanbase; the film maudit defenses are all but inevitable. But however close he feels to the material, Zemeckis has flattened a complex journey of self-discovery into a technical exercise at once egregiously sentimental and emotionally hollow—a plastic facsimile of human struggle. Only this director, perhaps, would even think to make a special effects movie out of Hogancamp’s story. Everyone else would have the good sense not to.