The Doctor is all alone in a perfect episode

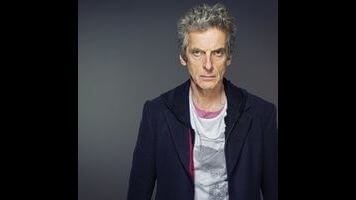

Let’s start with the blindingly obvious first: There has never been a Doctor Who episode like “Heaven Sent.” It’s a tour de force for writer Steven Moffat, director Rachel Talalay, and star Peter Capaldi, who is by himself for a good 95 percent of the episode’s running time. The episode is built around one of the greatest twists Moffat has yet devised, and not even necessarily because it’s so surprising—all the clues are there to work out what is going on, which is only a good thing—but rather because what it ends up saying about the Doctor. And while it’s easy to say this episode is all about the Doctor, given that he is pretty much the only character in the whole thing, the episode also deals at some length with Clara’s death in “Face The Raven” and what his lost companion means to him. The episode presents the Doctor at his most brilliant, most broken, and most resilient, and all that is directly informed by the grief he feels for Clara, and how he intends to honor her memory.

That closing montage is likely to dominate audience’s memories of “Heaven Sent,” and quite right too. But before we consider all that that scene means, it’s worth looking at what comes before. The opening sequence, in which the Doctor first wanders around the castle and demands his unseen antagonists show themselves, very much presents a man in search of an audience. This is a story without a companion, yet the Doctor always needs someone to talk to, so he still has little bits of self-banter about his hatred of gardening and his warning to his tormentors that he will soon enough be able to work out precisely where he is and what’s going on. And, of course, he uses the TARDIS inside his mind as a way to keep the spirit of Clara alive, talking out all his crises and concerns with her, even if she only truly appears beside him that one time. The conceit of having the Doctor step into the TARDIS every time he is in mortal peril could be little more than a bit of stylish cleverness—not that that would be the worst thing in the world—but what makes this storytelling device work is how much it ends up revealing about his character.

The deconstruction of how the Doctor’s blind leap out the window is anything but that is a marvelous bit of fun, with the Doctor even winking at the audience as he admits it probably spoils the magic a bit for him to reveal that every stray action was a way of testing the local conditions before deciding he could indeed survive his jump. The episode doesn’t even hint at this connection, but it’s interesting to look at how the Doctor’s decision-making process works in the light of what happened to Clara in “Face The Raven.” Even those of us who have been traveling with the Doctor for years—companion and audience alike—could so easily miss the insane amount of strategic thinking that goes into the Doctor’s every move, and so it would be tempting to think that it would be possible to replicate that for oneself. That was part of Clara’s mistake last week, after all. But the Doctor doesn’t just lead a charmed life, as really he’s two different kinds of genius. He’s a brilliant enough lateral thinker to always find the hidden alternative, and his brain is a powerful enough processor to work through all the variables to know whether his plan will work before he puts it into action. To borrow and twist Arthur C. Clarke’s old line, any sufficiently prepared plan is indistinguishable from magic.

As the episode goes on and the Doctor works out just why he has been brought to this castle, the tone of the story changes, with the Doctor’s initial irascible fury giving way to a full understanding of what’s actually going on. There’s very little Peter Capaldi does here that’s not worthy of praise, but I especially love his pained delivery of the line when the Doctor recognizes this place doesn’t just require truth, but confession. The show has flirted with the idea of the Doctor safeguarding certain truths that must never be revealed, most notably in “The Name Of The Doctor,” but that previous episode struggled because the 11th Doctor never did much but stand around looking mournful. “Heaven Sent” improves on this simply by placing the Doctor in a more direct life-or-death situation, with the Veil providing an immediate, ever-present specter of implacable, imminent demise. It also helps that the Doctor’s very first confession is to reveal that he genuinely is afraid of dying, and that he feels that way because the Veil is closing in on him, which instantly makes all that follows feel more visceral than it might otherwise. Besides, the Doctor does divulge some information, even if what we learn at first merely reiterates what the Doctor revealed to Davros in “The Witch’s Familiar.” It’s only with the true nature of the hybrid that the Doctor draws an absolute line, one that he never crosses—even when given a hundred billion chances to do so.

Let’s really think about that for a second. The Doctor at last reaches Room 12, and the word “bird” written in the sand makes him realize at last what has been going on. The look of horror on the Doctor’s face at that moment is palpable, as he tells the Clara in his head that he can remember every single time he has reached this room and died slowly, horribly at the hands of the Veil. He can see that wall, at least 20 feet thick, and he knows there’s not a chance that he will succeed this time or any time in the remotely nearly future. To keep on his present course is to consign himself to the worst possible death, lived out in near-infinite repetition. And yet … that’s the only solution. That’s the only way out, because the alternative would be to reveal the truth of the hybrid to his mysterious captors. He can neither trust these unseen antagonists with that information nor assume they will do anything but kill him should he reveal that final confession. So that way is to lose. The other option, as the illusory Clara puts it, is to win, yet winning means enduring unimaginable agony nearly a trillion times over, each time just to be reborn with his grief over Clara as fresh as ever. If that isn’t hell—and not just heaven for bad people—I really don’t known what is.

Yet the Doctor goes through with it. Every. Single. Time. He has that same breakdown, every single time, in which he wallows in entirely understandable self-pity before finding the solace and the strength he needs to face the next death on the way to his eventual victory. And that solace comes from Clara, from his companion, just as it always should. Last season made a big deal out of the notion that Clara functioned as this Doctor’s conscience. It was a decent idea, but it now feels like another way in which season eight was overly schematic, telling us things that this more effortless season nine has simply shown us. The Doctor has internalized Clara, letting her be the voice of all the best parts of him. She keeps him asking questions, and she keeps him fighting when he would be willing to surrender. That’s just about as beautiful and perfect a tribute as companion could ever hope to receive, and it feels so right that the Doctor, for all his dire pronouncements of what he might be capable of now that Clara’s gone, ends up being just about exactly who Clara always believed he could be.

As is often the case with the best Steven Moffat scripts, it takes at least a second watch for the full brilliance of “Heaven Sent” to become apparent. There are little mysteries, like the Doctor’s replacement outfit after he clambers up out of the water, that are easier to solve once you know entirely what’s going on, and the final montage has so much going on in it that it’s easy to not make the connection there. The Doctor’s opening monologue sounds like another grand Moffat statement on life, the universe, and everything, but it functions more precisely as a description of the Doctor’s situation, perhaps even as a warning from one Doctor to the next. The Doctor’s breakdown after he sees the word “bird” is plenty powerful on first viewing, but without the full understanding of the Doctor’s situation—which is only explained later, as the dying Doctor drags himself back to the teleport chamber—the natural interpretation is to think that the Doctor remembers all his previous heartbreaks, all his previous tragedies, and that he’s talking generally about his life instead of specifically about the latest round of hell he’s about to endure.

This is a meticulously constructed episode, one that works on every level. For those who revel in the narrative pyrotechnics that so often defined Moffat’s work with the 11th Doctor, “Heaven Sent” delivers that in a way the show hasn’t pulled off since “The Wedding Of River Song,” or maybe even “A Christmas Carol.” That closing montage is a sustained blast of exhilaration, laying plain just how impossible a hero the Doctor here, how truly committed he is to his infinitely repeated opening warning that he will never, ever stop. The accumulation of years and the gradual punching away of the wall, all as the Doctor gets another word or two into the Brothers Grimm story about a bird sharpening its beak on a diamond mountain, is nothing short of extraordinary, again the perfect nexus of Steven Moffat’s writing, Rachel Talalay’s direction, and Peter Capaldi’s performance. Yet this is also an episode that is willing to give the Doctor space to be emotional and vulnerable in a way that he needed to be after “Face The Raven.” The Doctor is given space to mourn, to grieve, and to suffer without the episode ever quite becoming maudlin, in part because Clara shows up and slaps some sense into him at the very moment when the Doctor threatens to do just that.

This season has been a remarkable achievement for the show, and, pending next week’s finale, it’s got a real chance to go down as the best season of the revival, topping even Matt Smith’s debut in season five. And hey, maybe “Hell Bent” will be the perfect capper to this season, or maybe it won’t. But the genius of the construction of this season’s endgame is that “Hell Bent” could be an unmitigated disaster and it still wouldn’t really undo the genius of “Heaven Sent” or “Face The Raven” before it. Those two do form part of a larger three-parter, but each has had its own particular story to tell. The first was all about the end of Clara. The second was the all about the survival of the Doctor. And the third? Why, nothing less than the return of Gallifrey. The Doctor wasn’t kidding when he said he came the long way round.

Stray observations

- I do wonder a little bit if the Doctor’s experience was any different the first time through, when presumably not all of the clues were in place yet. I also wonder if the Doctor’s final breakdown played out any differently toward the end of those billion years, as he realized he was so, so close to breaking through and might just have a chance of doing it this time. Not something I need to see, necessarily, but it again speaks to how fascinating this scenario is.

- There are so, so many nominees for Peter Capaldi’s finest moment here, but I think I have to go with something I only mentioned briefly in the review: his dragging his dying body back to the teleportation chamber, with his mind also more slowly dying in his mental TARDIS. His pain is palpable as he explains how slowly Time Lords die, and he wonders how much longer he can keep burning himself to create a new Doctor. Beyond functioning as the perfect metaphor for regeneration, the line points us to the horrible, wondrous truth: The Doctor can keep doing it forever if he has to. As a great Brigadier said, splendid fellows … all of him.