The Dog Days of summer are here to waste everyone’s time

The sort of romantic sort of comedy Dog Days contains roughly one dozen dog reaction shots. This may sound like a lot, but consider that the movie runs for 112 minutes (averaging one dog reaction shot every nine minutes and 20 seconds), features heavy screen time for five dogs (averaging approximately two and a half reactions per dog, though some are more reactive than others), and includes zero shots of a dog placing its paws over its eyes in mock consternation. By these metrics, Dog Days is a model of restraint, featuring many shots where dogs simply stare blankly, looking cute.

That’s what many of the actors wind up doing, too. Some contemporary comedies allow improv runs to take over scenes and bulk up the running time; Dog Days has multiple scenes that feel just as endless, only to curtail abruptly with what often sounds like a single alt-take where maybe the designated joke got enough of a titter on set to send everyone home in time for dinner.

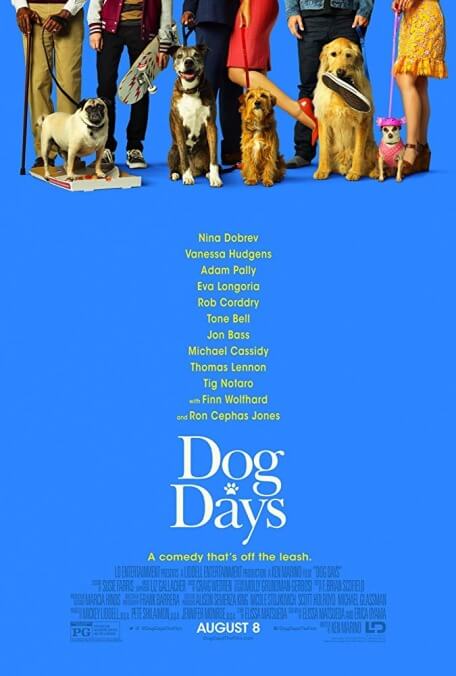

There are a lot of those scenes because there are a lot of those characters, loosely interconnected. Elizabeth (Nina Dobrev from The Vampire Diaries) hosts a Los Angeles morning show and mourns an unexpected break-up with her lousy ex (Ryan Hansen from Veronica Mars) before sparking with her talk show guest Jimmy (Tone Bell), a fellow dog owner. A couple (Eva Longoria from Desperate Housewives and Rob Corddry from Childrens Hospital) forge a connection to their newly adopted daughter when they find a lost dog, who actually belongs to a widower (Ron Cephas Jones from Luke Cage) in the midst of the world’s lowest-key feud with a pizza delivery boy (Finn Wolfhard from Stranger Things). Dax (Adam Pally from Happy Endings) cares for his sister’s unruly dog after she’s waylaid by the birth of twins, while his neighbor Tara (Vanessa Hudgens) volunteers at a dog shelter run by Garrett (Jon Bass).

It’s like watching a number of TV shows running simultaneously. Some of these stories seem to take place over the course of a few weeks, while others require closer to several months to unfold with any sense. Unless one or more of the dogs have been incepted, time in the Los Angeles of Dog Days is an elastic construction. Sometimes it even stretches and snaps back within a single scene: When Dax visits his sister (Jessica St. Clair from Playing House) and her new sons, infants who are supposed to be a few weeks old, the movie cuts between shots of St. Clair holding a real baby who is at least three months old and Pally holding what is clearly a newborn-sized prop doll mostly out of frame—and then awkwardly switches, giving St. Clair some shots with a prop baby and Pally some shots with a real non-newborn.

Pushed a little further, this could have become an actual goof on sloppy filmmaking, and comedy fans could be forgiven the assumption that this is the case, given that the director is Ken Marino from The State. Marino has written good studio comedies (Wanderlust; Role Models) and an impressive small-scale indie drama (Diggers), but here performs some kind of abhorrent black magic seemingly designed to raise Garry Marshall from the grave. Dog Days really falters when it tries to add in little asides and riffs, jokes that are nominally better than the barely there material in Mother’s Day but still wear out fast, because most of them depend on an actor saying something awkward and another actor either smiling politely (in scenes that are supposed to be romantic) or saying something like “that’s not a thing” (in scenes that are supposed to be funny). The movie deals in half-liners rather than one-liners.

If Dog Days were a little weirder, it would just be a smug anti-comedy takedown of a late-period Garry Marshall picture, like They Came Together with its biggest laughs edited out. As is, the film preserves an eerie façade of fakeness. Sets look dressed, but never lived in; characters have jobs, then don’t spend much time doing them; shots that depend heavily on green screen are nearly interchangeable with bits filmed on location. The only storyline that works reasonably well is the one with the adopted kid; its sweetness borders on saccharine, but it provides valuable resting time in between the other subplots straining for laughs. Like a series of moderate dog reaction shots, the sappiness of these scenes is unavoidable, unfunny, and a little cheap, but could be a lot worse. Dog Days, too, could technically be a lot worse. But without Marshall himself around to insist on softer punchlines and more dubbing, it’s hard to immediately picture how. Don’t say a cover of “Who Let The Dogs Out,” because the movie has that one taken care of already.