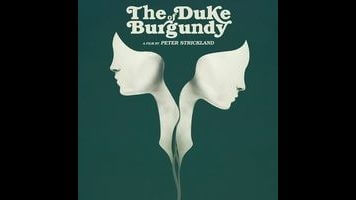

With a title that makes it sound like an 18th-century costume drama—perhaps a cousin to Jacques Rivette’s recent Balzac adaptation, The Duchess Of Langeais—and a marketing campaign that sells it as kinky erotica, Peter Strickland’s The Duke Of Burgundy risks attracting exactly the wrong crowd. For one thing, there’s no duke in the movie. Indeed, there are no men at all, as Strickland has created a mysterious alternate universe in which only one gender apparently exists, and reproduction is irrelevant. For another, while the film’s central relationship involves sadomasochism, and its overripe imagery mimics softcore ’70s pictures by the likes of Jess Franco and Radley Metzger, viewers hoping for cheap thrills will come away sorely disappointed. Nobody even gets naked—which is clearly by design. The Duke Of Burgundy employs outré subject matter for a magnificently mundane purpose. At its core, this is one of the most incisive, penetrating, and empathetic films ever made about what it truly means to love another person, audaciously disguised as salacious midnight-movie fare. No better picture is likely to surface all year.

Strickland opens with a dynamic between his two main characters that’s as misleading as it is provocative. Dressed in a way that suggests the past without specifying any particular period, a young woman named Evelyn (Chiara D’Anna, who also appeared in Strickland’s previous film, Berberian Sound Studio) arrives at the lavish home of an older woman, Cynthia (Sidse Babett Knudsen, star of the Danish TV series Borgen). Cynthia immediately chastises Evelyn for being late, then sets her to work on a series of demeaning, Cinderella-style tasks, eventually leading to equally demeaning sexual favors. (The most graphic acts, which include water sports, take place offscreen, implied by the soundtrack.) When the same sequence of events, featuring identical dialogue, recur on a subsequent day, it becomes clear that this is a consensual ritual that the two women share—a commonplace master/servant fantasy scenario. What also gradually, hilariously becomes clear is that Evelyn, the bottom, is quietly engineering everything that happens, while taskmaster Cynthia is a fairly inept top who’s only involved with BDSM in order to please her partner.

Strickland is clearly a heavy-duty cinephile—Berberian Sound Studio paid tribute to Italian giallo, and there’s a dream sequence here that includes an homage to Stan Brakhage’s avant-garde short “Mothlight”—and he has a lot of fun early on establishing the parameters of his Eurotrash softcore aesthetic. The movies he’s ostensibly aping, however, took place in an erotically exaggerated version of the real world, whereas The Duke Of Burgundy dispenses with literally anything that doesn’t meet the needs of its story. Other women are seen from time to time, but nobody does anything resembling “normal” work; the entire population appears to consist of amateur lepidopterists, who gather regularly to take turns giving lectures on various species of butterflies and moths. (Those who stay for the closing credits, which features a list of all the insects heard in the film, will learn that Duke Of Burgundy is the name of a butterfly, Hamearis lucina.) In a wonderfully sly gag, Strickland even places a few mannequins among the women attending these lectures, in order to underline the artificiality. Cynthia looks rapt as she listens to mating calls, while Evelyn struggles hard to appear knowledgeable, making observations that are snidely dismissed by the assembly.

Underneath all the kinky weirdness, in other words, is a simple, deeply moving portrait of two people who love each other despite having some very different interests, and who actively work—not without a great deal of frustration and some occasional rancor—to make each other happy. Anyone who’s ever sat through an entire season of some dumb reality show for their boyfriend’s or girlfriend’s sake, or agreed to go hiking for a weekend despite hating the outdoors and physical exertion, or indulged a lover’s harmless but unappealing fetish, or really just been in a long-term relationship at all, should have no difficulty relating. In one intensely funny yet heartbreaking scene, Cynthia tries to tell Evelyn how much she loves her, only to have Evelyn request degrading dirty talk instead; the result is so halting and hesitant that Evelyn, after her orgasm, thanks Cynthia and then asks if she could maybe have a little more conviction in her voice next time? It’s not an obnoxious or petulant demand, but something that Evelyn genuinely needs, which Cynthia just may not be able to provide. Is love alone enough? Strickland strips away everything that would distract from that question, then places it in a context bizarre enough to slip past calcified assumptions. Against all odds, he’s made a romantic masterpiece that includes sober discussion of a “human toilet.”

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.