The expanded history lesson in Saints & Strangers is still mostly one-sided

The story of Thanksgiving has grown inversely proportional to its accompanying feast—where the contemporary Thanksgiving dinner could likely feed all of the Pilgrims, the tale of the Plymouth colony has been pared down to bite-sized portions. It’s usually told in three acts, beginning with the religious persecution and a jaunt across the Atlantic, followed by the hungry and ill colonists meeting the indigenous peoples of Massachusetts, and ending with a happy meal and future holiday.

Obviously, the story of the colonization of the Americas is far more expansive and complicated than your average grade-school Thanksgiving pageant would have you recall. And to its credit, National Geographic sought to provide more of the history and conflict in its original docudrama, Saints & Strangers, which premieres Sunday. All of the characters featured were pulled from historical records of the colony, and the network employed indigenous actors and consultants to ensure authenticity in the native characters’ dialects and customs. Saints & Strangers is still ultimately a sanitized account of those days, but it’s not for lack of trying.

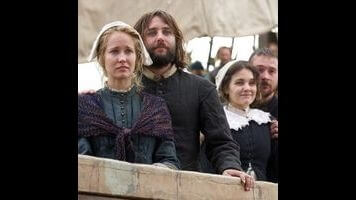

Mad Men’s Vincent Kartheiser leads the two-part miniseries as William Bradford (based on the real-life Plymouth governor), an English Separatist who spent some time in the Netherlands to enjoy religious freedom and get married and have a son. Bradford and his wife Dorothy (Anna Camp) have joined the Mayflower journey to lead a flock of Separatists in the “new world,” even if that means eradicating the locals. Somehow they’re the saints in this scenario, probably because they won’t be getting their hands dirty. That’s what the titular strangers are for, including Captain Myles Standish (Michael Jibson) and Stephen Hopkins (Ray Stevenson, in swashbuckling mode).

Those two monikers, saints and strangers, are mostly applied to the Mayflower passengers, because a third word exists for the peoples of the Americas, and that’s “savages.” Pious or not, the English colonists all invoke this term to justify their actions, as well as distance themselves from them (which doesn’t prove difficult). After a harrowing three months at sea, the colonists introduce themselves to the locals by raiding sepulchers and corn stocks. The desecration and theft are dismissed by the soldiers and rationalized by the pilgrims because after all, these actions haven’t been wrought upon actual human beings.

The portrayal of the colonists is honest and informed, yet never harsh. They’re sympathetic enough while on the ship that claimed multiple lives, including Dorothy’s (though it’s possible she committed suicide). And their motives certainly aren’t represented as wholly pure, even among the pilgrims. Kartheiser isn’t especially beatific as Bradford, and when push comes to shove (i.e., fortify the colony or build a church in which to worship) he makes the pragmatic decisions. Bradford never explicitly states that he’s doubting his faith, but even someone like Hopkins—who, among other things, is a murderer and mutineer—notes that Bradford has lost his way when he begins to attribute their fortunes, good and otherwise, to an entity other than God.

Multiple indigenous tribes are introduced throughout the four-hour event, but the focus is mostly on the Wampanoag (who are referred to here by the name of their village, Pokanoket). The tribe is led by Massasoit (Raoul Trujillo), a thoughtful man who speaks deliberately and advises vigilance when other local leaders are anxious to fight off the English threat. He’s just the kind of man you would expect to take in the last of the Patuxet, a man named Tisquantum (Kalani Queypo). Tisquantum, who is more commonly known as Squanto, acts as an emissary between the colonists and the natives, having made more trips across the Atlantic than anyone, English or Indian. Massasoit may be the leader, but Squanto is more of a visionary, a man who would see peace instead of more war. Despite the fact that his people were killed off by the European diseases brought by a previous group of colonists, he doesn’t appear to be bitter.

Squanto’s amenability sits especially well with Bradford, and even before the latter’s Plymouth governorship is made official, the two men find themselves at the center of all the diplomatic (and less so) activity. Squanto’s knowledge of the English language and culture, as well as his willingness to establish an agreement between their two peoples, ingratiates him to Bradford. The Plymouth colony governor (he soon replaces John Carver, played by Ron Livingston) eventually comes to trust Squanto even more than his countrymen.

Now, the scope of these events is inherently difficult to cover, even in a two-part miniseries. So the decision to focus on Bradford and Squanto is understandable, especially as they can make their plans in English and viewers the trouble of reading subtitles. Where people like Standish and Massasoit appear to be content with a detente, Bradford and Squanto are ostensibly pushing for something more permanent. But rather than allow both men to act as peacemakers, Saints & Strangers lets Bradford occupy that role for the most part on his own. The miniseries obfuscates Squanto’s motives and even represents him as a schemer. The English are mostly skeptical of the stranger, even if a cold New England winter without food should push them right into his arms, in a sense. And his own people doubt him, because he isn’t really one of them.

This shift halfway through the series creates an imbalance, one that the writers try to set right in the final hour with another meaningful interaction between Bradford and Squanto. But it’s too little, too late—once again, we have an account in which the natives’ motives are ambiguous, one that’s been mostly scrubbed clean of wrongdoing by the English. Saints & Strangers’ questionable return to established narratives (in which the pious Pilgrims were just innocent and incidental adventurers) offsets the other important work done to make this a more authentic representation of early colonial life.