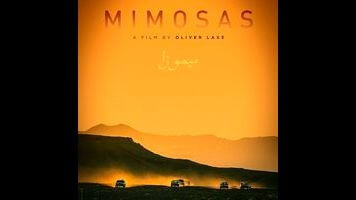

The experimental Mimosas traces an offbeat path through the mountains

One of the common threads in the last decade or so of experimental film has been the coincidence of folklore and film grain, as the filmmakers who have the clearest heads for anthropology and myth—whether they are established names like Ben Rivers (Two Years At Sea) and Ben Russell (Let Each One Go Where He May, the Rivers collaboration A Spell To Ward Off The Darkness) or newcomers like the duo of Samuel M. Delgado and Helena Girón—also share an interest in the properties of celluloid. Perhaps it’s part of a wider search for all things primeval: the rugged landscape, the oral tradition, the photochemical process, each promising to lead the artist back to something like the raw material of their origins. This is partly what the Morocco-based Franco-Spanish filmmaker Oliver Laxe is going for with Mimosas, his primitivist, shot-on-16mm fairy tale about a ragtag group of nomads tasked with carrying a body to a proper burial place on the other side of a mountain range. Laxe is a fellow traveler of Russell and Rivers (he starred as himself in Rivers’ The Sky Trembles And The Earth Is Afraid And The Two Eyes Are Not Brothers, which was shot partly on the set of Mimosas), but his work is less poetically arcane. He goes for unprepared authenticity.

To that end, Mimosas has two things going for it. The first is the geology of the Atlas Mountains of northern Africa, which is the sort of set design no money can buy. The expansive slopes and eroded limestone formations provide a canvas of timeless inhospitability onto which Laxe can paint his small, tattered travelers and their pack mules. The second is the diminutive Shakib Ben Omar, who first appeared in Laxe’s 2010 debut, You All Are Captains—a black-and-white meta-docu-fiction hybrid, much headier than Mimosas, and something of a personal statement on the geopolitics of filmmaking. Here he plays a character also named Shakib, a sort of holy fool who becomes the conscience of the makeshift caravan and, by extension, of the film project itself. With his scrunched voice and eccentric gesticulations (he uses his hands emphatically, but never raises them above his chest), Ben Omar’s character comes across like someone who has simply wandered on to the set and been given dialogue, especially when compared to the rest of the nonprofessional cast.

He is, in other words, utterly transfixing. Laxe latches onto the innate “stranger in a strange land” quality of his star. An anachronism, Shakib is introduced in a throng of job-seeking cab drivers, only to materialize later in a less historically specific era of mute maidens, bandits, and swords, where he joins the arduous trek to deliver the body of the old man, known only as the Sheikh. Laxe avoids directly articulating a relationship between the two different worlds of the film, except through the character of the pure-hearted Shakib, who seems to bridge them. Perhaps Mimosas is nothing more than a high-minded (but very affectionate) paean to naïveté, an incomplete adventure that eschews both sophistication and interpretation. But in the rocky foothills, glistening mountain ponds, and dusky desert vistas—and in those marriages of natural landscapes and natural light, scraggly terrain and 16mm grain, quest and Herzog-ian cinematic undertaking—it finds something close to the shared terms of myth.