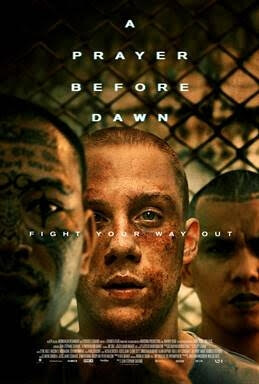

The facts aren’t gripping enough in A Prayer Before Dawn’s true story of prison-boxing glory

Most films adapted from memoirs come across as stranger than fiction. It’s not Billy Moore’s fault that his experiences—recounted in the 2014 best-seller A Prayer Before Dawn: My Nightmare In Thailand’s Prisons—call to mind a host of previous movies, albeit combining what are usually two separate genres. What begins as a standard-issue tale of horror in a foreign prison system (reminiscent of everything from Midnight Express to Brokedown Palace) eventually metamorphoses into an equally familiar boxing saga, complete with grueling training sequences and a climactic bout. Director Jean-Stéphane Sauvaire (Johnny Mad Dog) makes some audacious, impressionistic choices, focusing on the nexus of sensual and brutal, but this is the rare true story that really could have used some creative embellishment.

Right from the start, screenwriters Jonathan Hirschbein and Nick Saltrese choose to provide as little exposition as possible. We learn virtually nothing about Moore (Joe Cole), a young Englishman working as a boxer in Thailand, before he’s arrested on drug charges and tossed into the clink. No voice-over narration provides a window into his addled mindset; nor does he befriend another prisoner to whom he can confide his troubles (though he’s occasionally tended by a fellow inmate named Fame, with whom he develops a skeletal romance). Indeed, there’s little clearly audible dialogue in the film, and most of what’s said in Thai goes deliberately un-subtitled. For nearly an hour, A Prayer Before Dawn simply observes Moore—the sole white body in a sea of heavily tattooed Thai badasses—as he does his best to avoid getting beaten, gang-raped, or killed. He’s also still very much a drug addict, and somehow managing to score “yaba” (methamphetamine plus caffeine) from the guards, despite having no money.

A lot of details that are presumably explained in Moore’s book remain frustratingly vague here. While he eventually agrees to beat up some Muslim prisoners in exchange for drugs, that’s an exception to the rule; a guard hands him heroin as he’s initially being processed, and there’s no indication as to why. (Moore has no connections on the outside, not having told even his family about his incarceration.) Similarly, it’s unclear why Moore, who’d been trying to make it as a fighter before his arrest, takes as long as he does to join the prison’s Muay Thai boxing program. Half the film elapses before this obvious means of gaining respect and self-dignity apparently occurs to him, though it’s possible that he wasn’t given the option until that point. Sauvaire, it’s abundantly clear, isn’t much interested in Moore’s psyche, except insofar as it can be suggested via bodies in violent motion. He frequently allows Nicolas Becker’s low drone of a score to dominate the soundtrack, with random shouts and grunts dimly emanating from underneath; scenes shot in the boxing ring look almost peaceful compared to the constant threatening press of flesh elsewhere.

It’s an interesting approach, but one that required a different sort of actor in the lead role. As conceived here, Billy Moore has no past, no future, no personality, no friends, no dreams—nothing but the will to survive. He rarely speaks, can never be seen actively thinking, and demonstrates no interest in the sort of Machiavellian plots and schemes that usually dominate prison stories. Consequently, he needed to be played by someone with overwhelming physical presence, capable of drawing viewers in via raw charisma alone. Cole, who’s probably best known as John Shelby on Peaky Blinders, just doesn’t have that sort of compelling intensity. Give him an actual character to play, as Black Mirror’s “Hang The DJ” did, and he can deliver; A Prayer Before Dawn denies him any interiority, turning him into an inexpressive void. All that’s left is what happened to Moore, which echoes the harrowing road to redemption walked by numerous other movie protagonists. Sauvaire’s effort to make a prison-boxing equivalent of Beau Travail from these routine elements is admirable in theory, but it really needed Denis Lavant (and Claire Denis) in practice.