The Faculty is the bleakest and most subversive film of the ’90s studio teen-horror cycle

On its surface, The Faculty is a conceptually clever if fairly unsurprising tweak on the Invasion Of The Body Snatchers formula: What if your high-school teachers had been taken over by aliens intent on taking over the world? That’s a sound premise for a horror movie. What makes The Faculty stand out is just how slyly it executes.

Released 20 years ago on Christmas day, the film was a modestly successful slice of counter-programming, something for the kids who had no interest in seeing You’ve Got Mail or Shakespeare In Love with their families. Directed by Robert Rodriguez, it’s endured as an entertainingly glossy B-movie, with a script by Scream’s Kevin Williamson, who had initially planned to make it his directorial debut. It’s a clever teen-oriented fusion of Body Snatchers and The Thing—with a hint of Stepford Wives camp in the way the aliens turn everyone they possess into a well-mannered, conservative, overachieving versions of themselves. But the truly inspired and subversive elements of the film come in the way the story plays out: Not just in the choice to embrace drug use as a means of combatting the extraterrestrial invaders for the most productive use of narcotics arguably ever shown onscreen, but in how Rodriguez and Williamson slyly undercut the overt message of the narrative by implying that these people are not our heroes, and that even an alien invasion can’t wake people up from their boorish, nihilistic behavior. That’s a dark Christmas delivery, indeed.

At first glance, The Faculty actually looks like one of the more lightheartedly absurd entries in the studio boom of teen-centric horror during the back half of the 1990s. And that’s by design: Rodriguez was still in his early years of playing around with the genre tropes, coming off his first two big-budget films Desperado and From Dusk Till Dawn, the latter allowing him to undercut horror conventions as well as action beats. His fusion of postmodern stylistic tics and aim-for-the-cheap-seats populism had made a group of embattled humans being picked off one by one by bloodthirsty vampires into a daffily entertaining live-action cartoon, and producers presumably thought he would bring the same light touch to a horror movie about an alien invasion.

They were right. The director immediately got to work giving the story a splashy and animated rollercoaster vibe, from the freeze-frame character introductions (a charmingly retro rarity at the time, rather than a hoary rehash) to the camera’s restless roaming of the halls of Herrington High School, the fictional Ohio setting for the story.

There’s an unexpected (and wholly unjustified) jump-zoom on the face of Piper Laurie’s alien-possessed teacher that still crackles with goofball energy. The pairing of an over-the-top industrial cover of “Another Brick In The Wall (Part 2)” (performed by Alice In Chain’s Layne Staley and Rage Against The Machine’s Tom Morello, among others) with half-speed tackles and fireworks explosions during the small-town football game sequence makes for a stupid-smart bit of commentary on the absurdly overinflated importance of America’s second-favorite pastime.

Williamson’s script could easily have been played with a straight face—despite some scenes that openly reference classic sci-fi invasion literature, á la the meta self-awareness that characterized his breakout hit Scream—the movie is a more straightforward narrative that doesn’t muck about with deconstruction. Thankfully, Rodriguez knows the kind of pulpy material he’s working with, and leans into it, resulting in a messy but entertaining film. (For a different sort of entertainment, check out the now cringe-inducing Tommy Hilfiger ad campaign featuring the cast that aired during its release:)

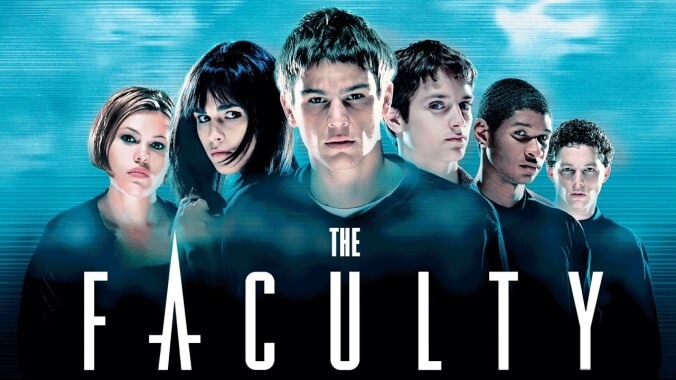

And that’s before any of the writer’s and director’s sneaky subversions of a teen sci-fi horror really sink in. The narrative follows a group of teens that, at first glance, come straight out of John Hughes’ stereotypes playbook: Casey (Elijah Wood), the bullied nerd; Delilah (Jordana Brewster), the popular queen-bee; Stan (Shawn Hatosy), the quarterback jock; Stokeley (Clea DuVall), the icy goth; Zeke (Josh Hartnett), the drug-dealing bad kid repeating his senior year; and Marybeth (Laura Harris), the sunny Southern new girl. After Casey finds a strange creature on the football field, the six band together when they realize alien parasites are taking over the bodies of the teachers and initiating a plan to infect all the kids, and soon the entire town.

Fleeing school, they realize any of them could already be infected—a fear that soon proves true when a test to demonstrate their humanity is failed by Delilah. After she flees, they follow her back to the high school, intent on killing the alien queen with a powder they’ve discovered kills the creatures and thereby (hopefully) frees everyone under the thrall of the parasite. They each fall victim, one at a time, to the creature (the queen is revealed to be new girl Marybeth, who eventually unveils her true form—think a giant cicada with tentacles), until Casey finally manages to stab the queen with the powder, reducing her to ash and destroying all of her parasites in the process. The movie ends with the kids embarking on changed lives, the news of the alien invasion now public record, albeit a disbelieving one.

But just as Williamson’s script is too smart to let its characters remain stock characters (we soon learn Stokeley’s a football fan, Stan wants to quit the team, Zeke’s a science prodigy, and so on), the movie is too sneaky to content itself with being a lazy assemblage of callbacks to other, better sci-fi and horror films. (Though there is copious borrowing—sorry, “homages”—to The Thing in particular, from the prove-you’re-human sequence to a repeat of that film’s disembodied head moseying around via tentacles.) Some of the commentary isn’t so much subtext as just plain text, as in the pre-credits scene, a mini-movie in itself (again, Williamson borrowing a page from the Scream strategy) wherein the principal (Bebe Neuwirth) is stalked and killed by the teachers already infected by the parasite. But before that, we get an entire scene of a teacher’s meeting in which she informs her staff that there’s no money for even the most basic school supplies, but that the football team will be not only getting new jerseys, but anything else they want. “This is a football town… my frustrated hands are tied,” she says, an aside that’s also a damning indictment of America’s school system, included simply to show that everyone in this movie is already a victim before the bodies start dropping.

But the best element of The Faculty, and one that gets almost no discussion, is the sly pro-drug-use message smuggled into the narrative. A key plot point of the story is the kids’ discovery that a certain substance kills off the aliens if they come into contact with it. This substance is “Scat,” an odd quasi-psychoactive drug Zeke makes himself and sells to kids at school. “Guaranteed to jack you up,” he assures his clients, with the slick patter of a teenage drug dealer as written by an older white guy in Hollywood. Along with its qualities as a stimulant, it functions like a hyper-speed diuretic, intensely and quickly dehydrating the user. (It’s made from “caffeine pills, some other household shit,” according to Zeke.) The aliens, we’re shown, require almost constant water to survive. Hitting them with the drug is akin to electrocution—they freak out, shudder, and die. A hit of the drug for a red-blooded American teenager, on the other hand? Incredibly awesome.

And that’s the hinge on which the entire movie pivots: The only real way to demonstrate your humanity in this world is to get high. Either you’re willing to snort drugs for god and country or you’re clearly an agent of evil. “He’s tweaking, let him fuckin’ tweak!” Zeke insists when another character dares to try and rain on the parade of good times had after Casey is the first to sniff up his dose of Scat to prove he’s still himself. This is how we know we’re human: We can handle our drugs. “There are not enough drugs in this world,” Nurse Harper (Salma Hayek) mutters to herself earlier in the film. The climactic showdown with the alien queen ends when Casey traps it behind the gymnasium bleachers, whips out a tube full of Scat, and reiterates Zeke’s feel-good promise: “Guaranteed to jack you up.”

It’s a wonder Williamson’s tactic didn’t get called out by executives at Dimension worried about pissing off anti-drug forces, a coalition always strong in Hollywood, especially when it comes to kids. But somehow a film explicitly marketed to teens which insisted that doing drugs was not only cool, but just might be your patriotic duty as a young citizen of the world, was released into the world on Christmas Day to spread a message of joy and pro-drug celebration. Hunter S. Thompson would be proud.

But the equally potent, and arguably just as subversive, subtext to the ending of the movie turns it into a much darker and more lacerating piece of satire. After defeating the alien, the film’s coda jumps to a month later, when we see where our heroes have ended up. Burnout drug dealer Zeke is now a full-fledged member of the football team (and it’s implied he’s dating a teacher, Miss Burke, played by Famke Janssen), albeit still enough of a rebel to enjoy a smoke on the field in between plays. Former goth Stokeley is now devoid of her all-black aesthetic, prettied up à la Ally Sheedy in The Breakfast Club and dating former-athlete-turned-academic Stan. And Casey is now dating the most popular girl in school, Delilah, the two of them fielding offers from local and national news outlets to give exclusives on how he vanquished the alien menace.

A straightforward reading of the conclusion would imply these former outcasts have now bought into the very system they were previously rebelling against, the movie’s happy ending a conservative endorsement of the idea that goth girls just need to find a cute dress and a boyfriend, that rebels need some discipline as members of a sports team, that meatheads just need to study harder. For a movie that seemed to be a screed against conformity, this would appear to be a betrayal of all that had come before. “What a disappointment,” it was recently argued on the Faculty Of Horror podcast. “Our favourite misfit students really just want to be like everyone else after all,” criticized Den Of Geek. And this seems to be the dominant interpretation, even from fans of the movie: A fun ride that botches the landing.

But there’s a far darker reading of the film, one supported by the visual story Rodriguez is telling, a thread that cuts against the grain of the actual dialogue, undercutting and mocking the very words uttered by the characters. The conservative assessment misunderstands what the film is trying to do: It’s not showing how trials and tribulations can help misguided kids come to their senses and join the system. It’s saying there is no outside the system to begin with. The entire structure of school and the kids within it, according to this interpretation, is destined to repeat, over and over, the same cliques, prejudices, cruelties, and impersonal forces of pain that mistreated our protagonists so badly in the first place. These characters can’t see beyond themselves far enough to realize that the world hasn’t improved, they’re just occupying different places in it.

This is best exemplified by the role of the bullied in the film. During the character introductions, we watch as poor Casey gets lifted up and rammed repeatedly in the flagpole, crotch-first, collapsing on the ground in pain. Silently bearing his torment, Casey’s misery is meant to show us Herrington High is not a good place. But at the end of the film, when his new beau Delilah goes arm in arm with him off to meet the latest wave of reporters, Casey marvels at how the alien invasion has turned things around at his school. “Things sure have changed, haven’t they?” he says, and as he does so, the exact same bullies from earlier in the film enter the frame, and run a new kid, crotch-first, into the flagpole. Contrary to the dialogue, the film suggests Casey is wrong, that things haven’t changed at all. Appearances may shift, but the underlying structure remains untouched. There is no success here; things aren’t better for having saved the world from alien invasion.

It’s a borderline nihilistic message, and a much more interesting one than a straightforward interpretation of events would offer. The Faculty works so well because it zigs where a zag is anticipated, because it belies the surface of its story with a far bleaker one underneath. And most of all, it just wants everyone to do some drugs. Robert Rodriguez and Kevin Williamson tweaked their noses at acceptable teen-movie messaging; let them fuckin’ tweak.