The fiction must match the reality in The Little Drummer Girl premiere

“I pray you, do not fall in love with me / For I am falser than vows made in wine”

—-As You Like It, Act III, Scene V

On some level, all spy stories function as metaphors for performance. After all, professional deception (and/or self-deception) requires advanced dramatic skill and an innate ability to pathologically lie. It may be a cliché to say that “life is a performance,” but how much of that daily acting is glorified social lubrication and how much is flat-out dishonesty? A white lie to a spouse and a top-to-bottom fabrication in order to take down a violent terrorist cell feel leagues apart in the abstract, and yet espionage means accepting the discomfiting truth that they’re much closer than they appear.

During a routine audition, Charmian “Charlie” Ross (Florence Pugh) molds a story about an uninteresting bar confrontation—one where she ultimately comes across as misguided in her defense of a drunk gay friend following a brush with casual homophobia—into a raucous, romantic tale of a violent bar fight turned meet cute. Her direction was to take the essence of the scene to make it her own, and in turn, she created a larger-than-life fiction into which she could invest her entire emotional being. A pub actress she may be, but she’s had an inveterate career as a liar.

Israeli spymaster Martin Kurtz (Michael Shannon) feels all too comfortable assuming the most advantageous persona depending on which room he enters. When he’s talking to Dr. Paul Alexis (Alexander Beyer), Department Six operative, he’s Shulman, friendly government official who wants what’s best for West Germany. When he’s talking to Mr. Fineberg (Vitali Friedland), victim of a bombing that killed his Talmudic scholar uncle and eight-year-old son, he’s another red-blooded Israeli man who understands why he allowed a beautiful Western au pair to leave a mysterious suitcase in his home. When he’s talking to Shimon Litvak (Michael Moshonov), he’s a fellow Israeli operative who understands the sacrifices and anger it takes to undertake such a cold-blooded profession. Like all spies, Kurtz is many men at once, able to assess situations and people with disturbing ease. To state the obvious, he and Charlie aren’t much different.

The first episode of The Little Drummer Girl, adapted from the 1983 novel by John le Carré (also an executive producer on the series), primarily focuses on Charlie and Kurtz as they’re slowly brought together by a retired Mossad agent (Alexander Skarsgård) to collaborate on a dangerous assignment. A Palestinian terrorist cell run by a mysterious Khalil has been bombing Jewish targets all over Europe using Westerners as assets. Khalil, whom Kurtz compares to Mozart and might as well be his White Whale, uses his little brother Salim (known to the world as Michel) to fold wayward women into the cause. To fight fire with fire, Kurtz decides to train a gentile civilian to infiltrate Khalil’s network and bring down the cell from the inside.

“Episode 1” functionally requires a lot of table-setting, as does most le Carré adaptations, but writer Michael Lesslie succeeds at shrouding most of the plot in a veil of mystery, purposefully leaving out clarifying details and refusing to spoon-feed character names and historical context for the audience. The confidence of the plotting disguises some of the rushed-for-time machinations to get the characters where they need to be, a necessity when bringing a 500+-page book to life.

Director Park Chan-wook (Oldboy, The Handmaiden, Stoker) helps communicate some of the subtler details from Lesslie’s script and craft an emotional atmosphere befitting his characters. Watch how he introduces Skarsgård, fractured and bathed in the shadows, with red stage lighting from Charlie’s theater troupe’s production of Saint Joan reflecting brightly off his wristwatch. Notice how he emphasizes environments in wide shots—the hallways of Mossad HQ, a Munich safe house, the Parthenon—blocking his characters off-center to illustrate how much their chosen worlds constrict their personhood. Or, even more simply, observe when he chooses to shoot someone in close-up, such as Kurtz explaining to his superior how they must use a “live goat” to catch a lion, and how restricting the use of that tool creates its own meaning.

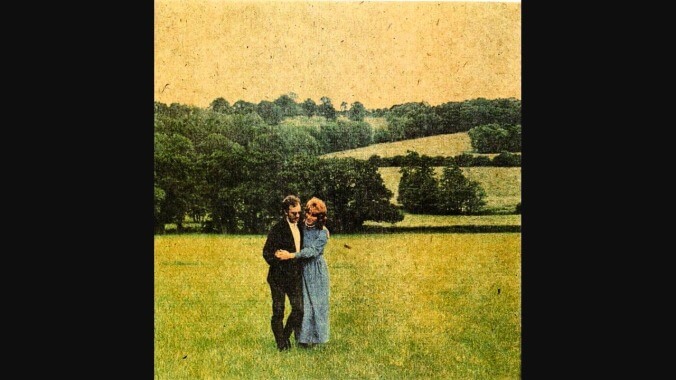

The episode’s main source of mystery is Skarsgård’s character, Peter (or Joseph/José, as Charlie calls him, because of his “coat of many colors”), the international man of mystery responsible for bringing Charlie and her troupe to Greece. Peter lingers in the background and doesn’t say much, but right on cue, Charlie becomes fascinated by him, at first out of annoyance then genuine curiosity. He uses delicate cues to garner her favor, such as a penchant for Boutaris wine and Chilean socialist politics, but it doesn’t take much convincing to whisk her away to Athens for a couple days under the guise of a romantic getaway. One can maybe quibble with the plausibility of such an adventure, especially given that Lesslie/le Carré has established Charlie as snarky and perceptive, but Park relies on Pugh and Skarsgård to sell their mutual attraction, which they do fairly well. (Plus, Park also takes care to capture Skarsgård’s beach-ready physique as a sufficient motivator as well.)

But their date goes sour after a sudden trip to the Greek ruins after hours. Peter, who, if you can believe it, is not who he says he is, hastily brings Charlie to a safe house harboring Kurtz, Shimon, and the rest of the team so they can start briefing her for her new job. Rachel (Simona Brown) has already captured Salim on the Greek-Turkic border with a car full of explosives. He’s on his way to the Munich safe house where Kurtz has just installed a soundproof isolation room exclusively for his pleasure. Things are already moving quicker than anticipated.

“I am the producer, writer, and director of our little show,” Kurtz informs Charlie with just enough air of mystery, and which only furthers the performance metaphor baked into Little Drummer Girl. Charlie, like Peter, is an actor, one whose job is to craft a fiction that matches the reality of their targets. Charlie, though anti-Zionist, mentions at a party that she believes peace between Israel and Palestine can be achieved without violence. For better or worse, Kurtz is looking to put those principles to the test.

Stray observations

- Welcome to The A.V. Club’s coverage of The Little Drummer Girl. Those living in the UK will have a head start on the first four episodes. To them, and those who’ve read the novel, no spoilers, please! AMC will air two episodes a night for three nights in a row leading up to Thanksgiving.

- The quotation at the top is spoken by Rosalind, Peter’s favorite of Shakespeare’s leading ladies, and one that resembles Charlie quite a bit.

- Some character details aren’t conveyed with as much care as others. The characterization of Shimon feels very sketchy and forced, pigeonholing him in a zealot’s role without much nuance. Ditto Salim, though he doesn’t have nearly as much screen time in this episode. With that said, Salim listens to Peaches & Herb’s “Shake Your Groove Thing” in his car, which actually suggests quite a bit about how he lures Western women into the cause.

- If you’re interested in the song that Charlie sings at the beach bonfire in Greece, it’s “The Murder of Maria Marten,” an old English folk ballad about the murder of a young woman by her lover before they were set to elope. Below is the version recorded by Shirley Collins and the Albion Country Band from their 1971 album No Roses, featuring Richard Thompson on electric guitar.