The Final Year is both a love letter and gut punch to the Obama presidency

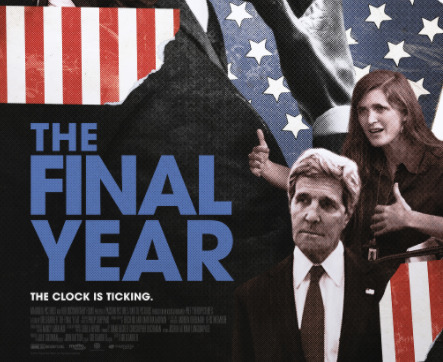

As it did to many things, the election of Donald Trump transformed The Final Year from what should have been a triumph into a tragedy. The documentary follows—and frequently lionizes—three Obama officials throughout 2016, and frequently feels like it was intended as a well-deserved victory lap. Secretary Of State John Kerry, Ambassador To The United Nations Samantha Power, and Deputy National Security Advisor Ben Rhodes are exactly the types of people you’d expect were energized by Obama’s election and vision. Kerry, obviously, had his own political background, but Power and Rhodes were swept from other careers into public service by the tantalizing idea that they might actually make the world a better place. For a while, they did. President Obama, the pragmatic idealist, had that effect on people—he made them want to do good.

Every big issue covered in the film can’t possibly be done justice in 90 minutes, but even getting the broad strokes here offers more solid information than could be found on the nightly news—especially during the circus-like election year. (“They’re talking about Trump’s Twitter feed,” says Rhodes at one point—which could have been any point in 2016 and since.) But The Final Year makes a solid case for the Obama years’ foreign-policy effectiveness, shining a light most specifically on the nuclear deal with Iran, normalization of U.S.-Cuba relations, and the ratification of the Paris Agreement on climate—all potentially huge steps toward a more just and peaceful world. The almost disarmingly reasonable Kerry feels like a hero here, as he repeatedly makes the case that diplomacy, though harder than military action, will almost always provide more lasting results. These people feel like they’re making the world a better place, and they probably are.

It’s not all sunshine, of course: There are practical reasons that the administration’s hands were tied on Syria, for example, and Power visits Nigeria, where Boko Haram kidnapped 276 girls in 2014. (Many are still unaccounted for.) And Obama visited Hiroshima and Laos in 2016, two places devastated by conflict with the United States, in a continuing attempt to salve old wounds. It was all very presidential, and seemingly motivated by altruism rather than politics. But the specter of a Trump presidency invades the later parts of the film, first as a distraction from real issues and then as a looming threat to destroy the very things that this group worked so hard to implement. Cameras followed Power and Rhodes on election night, and watching their reactions is like living that shitty moment over again, only with the hindsight that Trump would indeed attempt to torpedo everything they’d done. Rhodes, a speechwriter who’s always ready with something smart to say, can’t even find words immediately after. Later, he says one of the scariest things about the Trump presidency you’ll ever hear: “People assume there are some grownups somewhere that will make sure he doesn’t screw up too bad—there’s not.”

Director Greg Barker ends The Final Year on a semi-hopeful note: Obama himself granted the filmmaker some brief interviews for the movie and, ever the optimist, the soon-to-be-former president has some comforting words. Still, it’s hard not to watch The Final Year as a depressing reminder of the actual political consequences of the last election, and a portrait of important work undone seemingly on a whim—or out of spite. Obama would probably view it as a minor setback in the grand scheme, but at this moment in history, it feels like a twist of the knife.