The first Harry Potter movie preserved everything in the book… except its magic

Image: Graphic: Rebecca Fassola

There was always going to be a Harry Potter movie franchise. As soon as the first J.K. Rowling novel ascended the New York Times bestseller list, it was inevitable. The gods had handed Hollywood a rare gift: a literary phenomenon, huge among children, that was written nearly as visually as a movie script and that already had its sequels built in. Studios get a lot of criticism these days for leaning too heavily on recognizable intellectual property, but they’ve been building big-budget films out of popular novels since the silent era. The first Ben-Hur movie, after all, came out in 1925. When a book sells a few million copies, it almost invariably becomes a movie. Harry Potter was a no-brainer.

Before Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone first went into production, the big question in Hollywood was who was going to direct that first movie. The obvious first choice was Steven Spielberg, but he turned the job down, later explaining that the task would’ve been too easy. But it might not have been that simple. According to some reports, Spielberg wanted to cast Haley Joel Osment, who’d just been Oscar-nominated for The Sixth Sense, as Harry Potter, but Rowling, who had an unusual level of control over the adaptation, insisted on an all-British cast. In any case, Spielberg was out. That year, he made A.I. Artificial Intelligence with Osment instead.

An Entertainment Weekly story from 2000 about the search for the Potter director makes for a fascinating read. The movie reportedly could’ve gone to Jonathan Demme or Steven Soderbergh or M. Night Shyamalan. Sam Mendes, Rob Reiner, and Wolfgang Petersen all reportedly withdrew themselves from contention. Rowling supposedly really wanted Terry Gilliam, the former Monty Python member and notorious weirdo who was coming off of 12 Monkeys and Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas and who was probably at his peak as a pop filmmaker. Gilliam was furious that he didn’t get the job; he later described the first two Potter movies as “shite.” Instead of making Potter, Gilliam lost years to his famously cursed Don Quixote adaptation. He didn’t get anything into theaters until the 2005 flop The Brothers Grimm.

Instead, the man picked to direct Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone was Chris Columbus. Of course it was. It’s amazing that there was ever any question. In 1990, Columbus, a Spielberg protégé who’d written Gremlins and The Goonies and who’d only directed a couple of movies, came out with Home Alone, a historic monster hit that sent kids into frenzies. Home Alone isn’t a fantasy movie in the Harry Potter sense, but it’s a fantasy in that it shows a kid successfully mauling adults, an actual childhood wish-fulfillment scenario.

Columbus cranked out family films all throughout the ’90s, and most of them, like Home Alone 2: Lost In New York and Mrs. Doubtfire, were big hits. Columbus’ last effort before the first Potter was Bicentennial Man, a weird 1999 failure where Robin Williams plays a robot butler. But it gave Columbus some experience with special effects. He was a creature of the studio system with a proven track record and a gift for working with child actors. The choice was clangingly obvious. In choosing Columbus to make that first Potter, Warner Bros. ensured that the movie would be a half-decent crowd-pleaser, while eliminating any chance that it might be great. From a sheer business perspective, this was definitely the right choice.

You can see the thinking here. Harry Potter was a potential goldmine. Terry Gilliam was a vivid, inventive visual director who might make something astonishing with Potter but who might also turn it into an incoherent disaster. The same is true of any ambitious director who could’ve been selected. Warner couldn’t afford to play around with that. The Potter books had fans, and those fans wanted to see the movies depicted as literally as possible. The studio needed a steward, and Columbus was it.

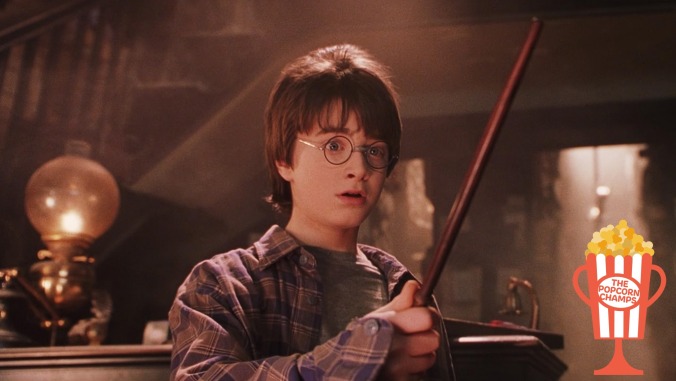

It’s weird to think about now, but most big literary adaptations of the pre-Potter era are significantly different from their source material. The Godfather and Jaws excised entire subplots from their novels. Jurassic Park changes around who lives and who dies. Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone, on the other hand, makes only the most minute and cosmetic alterations. The movie’s producers were so consumed with nailing the book as accurately as possible that Daniel Radcliffe, the young actor chosen to play the title role, initially had to wear contact lenses to change his eye color to more accurately reflect Rowling’s prose. (The lenses irritated his eyes, so Radcliffe was allowed to lose them… but only after Rowling gave the okay.) Even with its almost militant faithfulness, some people were still mad. I remember my little sister, a big Potter fan, being angry that Radcliffe’s hair wasn’t messy enough.

With a movie like Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone, the goal wasn’t really to make a great film. The goal was to avoid fucking it up—to clear the runway for future sequels and spinoffs and amusement-park rides. From that perspective, the movie was a roaring success. In casting the picture, Columbus somehow found a group of kids who could make it through a massively popular eight-film series without going nuts from all the attention or turning into weird-looking adults. He set a visual template that served the rest of the franchise well. He crammed in vast reams of expository dialogue without losing all narrative momentum. He did his job.

But god, it’s boring. Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone is a strange contradiction: a work of magic and imagination, rendered with no magic or imagination whatsoever. Columbus’ visual style is a clumsy simulacrum of Spielberg’s grace and wonder. His comic-relief characters mug and preen and gloat. His child-actor leads are forced to spend way too long laying out twisty mystery-plot mechanics. The whimsy is forced. The jokes mostly land with thuds.

Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone isn’t a long book, but it’s jammed with plot. Since the film has to set up all the sequels, it has to get a lot of plot in there, which turns it into a terribly long two-and-a-half-hour trudge. Columbus covers all the necessary real estate, but it makes for rough going. Every time my kids have wanted to watch The Sorcerer’s Stone—and they’ve wanted to watch it a lot—it’s been a chore to sit through. The movie plays a bit like a TV-series pilot. If a phenomenon like Harry Potter came along today, I have to imagine that it would become a big-budget TV show for some streaming service rather than a series of films. It would probably work better that way.

Columbus does have a few inspired moments in The Sorcerer’s Stone. His best decision was probably bringing in John Williams to compose a tingly, playful music-box score that, in retrospect, is pretty similar to the one he had done for Home Alone. (There’s plenty of Home Alone DNA in that first Harry Potter; Harry’s cousin Dudley, for instance, acts more like Kevin McAllister’s brother, Buzz, than like the Roald Dahl-esque caricature that Rowling put on the page.) I like some of the individual shots: The boats floating across the lake toward Hogwarts, the cloak looming above Harry in the Forbidden Forest. The special effects in the big quidditch match work surprisingly well, and the film takes a rare pause to let Harry feel some triumph.

Most importantly, the acting is better than anyone really had any right to expect. Columbus was smart to cram the film with absurdly overqualified Shakespearean character actors who had the gravity to sell all the ancient rituals: Richard Harris, Robbie Coltrane, Julie Walters. Maggie Smith had two Oscars when she took the Professor McGonagall part. Alan Rickman absolutely savors every bit of snarling assholism that the Professor Snape role grants him. John Hurt is in there for all of one scene, but it’s a crucial scene, and he finds just the right note of twinkly mysticism.

Those adults do most of the heavy lifting for the child actors, who definitely come off as child actors. But Daniel Radcliffe, who’d already played David Copperfield on the BBC, has enough charm and sensitivity to work in what couldn’t have been an easy role. As Ron Weasley, Rupert Grint has to do way too much gawping, but he sells his jokes pretty well. Weirdly, the only real weak spot is Emma Watson, the one of the three who became both a great actor and a movie star. In that first film, she hits her one priggish note way too hard, again and again. (She did better in the sequels.)

Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone came out into a world that was absolutely ready for it. The 2001 box office was utterly dominated by fantasy films. The year’s two biggest hits were both CGI-heavy, franchise-starting spectacles about tiny people who are whisked away from quotidian provincial lives to go on magical adventures with their friends, turning invisible and fighting trolls and being menaced by black-cloaked figures. Both movies have evils returning from generations past and kindly, mysterious wizards with giant white beards. Harry Potter only barely outgrossed The Lord Of The Rings: The Fellowship Of The Ring, a much better film, but the two sagas clearly scratched some of the same societal itches.

It’s tempting to imagine that the Harry Potter and Lord Of The Rings movies both gave a sense of escapism to an American population that needed it; The Sorcerer’s Stone and Fellowship Of The Ring both arrived in theaters a couple of months after 9/11. But the year’s other hits are mostly pretty similar in both tone and subject. By some amazing coincidence, the troll in Sorcerer’s Stone looks eerily similar to the title character of Shrek, the year’s No. 4 movie. (I have to say: The Potter kids take out that troll way too easily. The Fellowship Of The Rings troll must be embarrassed for that guy.)

Monsters, Inc. and The Mummy Returns played to the same audiences, too. Some of these were based on established properties, and some had big stars, but all of them found some balance of broad comedy and daffy adventure. I don’t think these movies succeeded because of anything to do with 9/11. I think it was just a generational thing. In 2001, the oldest millennials were 20, and the youngest were 5. There were a lot more kids out there in the world, and kids like stories about castles and monsters.

After The Sorcerer’s Stone, the Harry Potter movies remained a money machine for Warner Bros. For the next decade, they came out regularly. Columbus returned for the first sequel, 2002’s Harry Potter And The Chamber Of Secrets, but that was the man’s last big hit. Alfonso Cuarón took over on 2004’s The Prisoner Of Azkaban, easily the best entry in the series, and Columbus went on to make a series of flops: The Rent movie, I Love You, Beth Cooper, Pixels. Columbus tried to recapture the Potter magic with 2010’s Percy Jackson And The Olympians: The Lightning Thief, an adaptation of a kid-lit novel that blew up in the wake of the Potter books, but he whiffed that one big time.

He had more post-Potter success as a producer, helping shepherd things like the Night At The Museum series and The Help. (Columbus was also an executive producer on Robert Eggers’ The Witch, and it’s intense to realize that the man who might be history’s most successful kiddie-fantasy director was also involved in a film where a baby gets mashed into paste in the first 10 minutes.) But Columbus is still finding work as a director. In fact, he just came out with The Christmas Chronicles 2, the Netflix sequel where Kurt Russell once again plays a hot Santa. I just watched that one with my kids. It fucking sucks.

The contender: The big family-fantasy hits of 2001 didn’t really rely on movie stars. Within the year’s top 10, the one real outlier is a pure throwback, a movie that is basically nothing but movie stars having fun and being charming. In its own way, Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Eleven is a fantasy, too, since you can’t watch it without desperately wishing you could hang out with its characters. It’s also technically an intellectual-property movie, a remake of an old Brat Pack heist romp. But Soderbergh’s film transcends its source material. It’s a near-perfect entertainment that doesn’t lose any luster after a dozen rewatches.

That first Ocean’s was the peak of Soderbergh’s brief run as a populist champion; he’d made both Erin Brockovich and Traffic the year before. Soderbergh remains a restless, fascinating filmmaker who’s done a lot of great stuff since then. But Ocean’s Eleven is a rare piece of work: a movie that forces you to fall in love with everyone onscreen. Soderbergh makes it look easy, but if it was easy, more people would do it.

Next time: Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man swings in, inaugurating the ’00s superhero-movie boom in a big way.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.