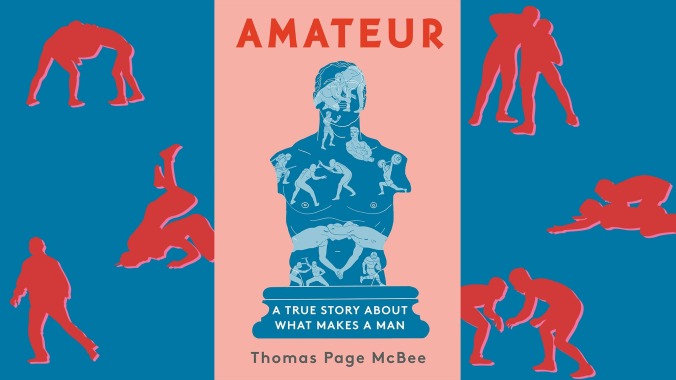

The first trans man to box in Madison Square Garden spars with masculinity

A boy isn’t supposed to hit a girl, even when she throws the first punch. It’s the first thing many of us learn about masculinity, on the playground or the school bus. So it feels familiar when Amateur author Thomas Page McBee panics when asked to spar with fellow boxer Larissa. It doesn’t matter that she’s been outperforming him in drills. She’s still a girl. Meanwhile, Larissa hollers gleefully to just throw a punch already.

Normally an office-dwelling journalist and author (previously of 2014’s Lambda Award-winning memoir Man Alive), McBee has decided to box with Haymakers For Hope, a cancer nonprofit that invites amateur boxers to gather pledges and fight in professional boxing venues. His fellow boxers—many of them white finance bros—are sirened by this blend of charity and the opportunity to punch another man in the face. But McBee has other designs: He wants to better understand masculine aggression and conditioning, and thinks this might be the way to do it.

At the time of this decision, McBee has just five months until the match. He’s messy and tentative in the ring, quiet and non-confrontational in the locker room. (This is partially for safety’s sake; he’s a trans man in largely cisgender spaces, around men he doesn’t know and so can’t immediately trust.) It’s even unclear whether the fight organizers will be able to find someone in his weight class—at 132 pounds, he’s lighter than most participants.

McBee isn’t just a beginner at boxing; he’s also a beginner at interrogating his place in the world as a man, having transitioned at the age of 30. (He’s 34 by the time he’s in the ring.) It’s this “beginner” status that allows him to offer up this inquisitive, sincere examination of contemporary American manhood. In high school a hook-up pronounced him “like a guy, but better,” but now that the world relates to him as a man, he’s pressed to figure out what else “better” means.

In order to do so, McBee spends time with a wide array of experts—from sociologists to race historians—but moments with those closest to him yield the most crucial revelations. As he’s proudly practicing his jabs in the bathroom mirror, finally getting the hang of things, his partner, Jess, asks him to stop, relating a particularly frightening instance of street harassment:

“A man on the street followed me for blocks today, saying ‘I want to fuck you and to kill you.’”

It’s understandable, McBee concedes, that she’s not terribly interested in watching him shadowbox: She doesn’t need to be reminded that the man she loves can also “be a man worthy of fear.”

McBee pays attention here and elsewhere to his own white male privilege, to class, to race, and to trans (in)visibility. There is something truly exciting about a book about masculinity that understands that these concerns are integral to its focus. And Jess’ voice, along with those of McBee’s siblings, are as clear and enriching and occasionally devastating as any source could be. It’s an extension of McBee’s willingness to do research in his own life, to find the answers he’s looking for as he learns the ways in which his “body [has] transitioned from threatened to threat.”

With less success, the book pushes past the personal into the sociological, inspecting workplace gender bias, different kinds of “passing,” why men might veer from platonic touch, the false link between testosterone and aggression, and, in one truly arresting biographical montage, the shifting self-narrative of boxing’s tragic bad boy, Mike Tyson. To accommodate the book’s countless topics and intellectual alleyways, McBee uses his genius for association and nimble structural moves. Still, it’s a lot to pack into such a thin volume, which weighs in at just over 200 pages. As a result, its discussions can sometimes feel fleeting, moving more like a feature article than a book. Perhaps this is by design—it’s understandable that the last thing McBee might want is a doorstop of a book suggesting that men talk less and listen more.

Amateur works well as a kind of syllabus. (To this end, McBee offers a “Further Reading” list at the end of the book, which offers texts by the likes of bell hooks and Rebecca Solnit.) Attentive readers might add McBee’s own potent first book to that list, the braided book-length essay about childhood abuse, a nearly fatal mugging, and the beginning of his transition. A kind of companion piece, Man Alive poses some of the questions that Amateur is trying to answer.

For all its occupations and interrogations, the book only glances at the full spectrum of gender, including people who are nonbinary or otherwise genderqueer. It’s a missed opportunity, but ultimately, McBee is working from inside the binary. He’s interested in gender conditioning and how it influences the way men—and, collaterally, women—live and interact. The hot center of this book, the new work that it does, is McBee’s search to identify and adopt ways to be a “better” man. He wants to know, as a man, how to fight gender inequity. “People sometimes think that being trans means I live ‘between’ worlds,” he writes, “but that’s not exactly true. If anything, it has just created within me a potential for empathy that I must work every day, like a muscle, to grow.” At a time when equity of all kinds is being suppressed, Amateur is a reminder that the individual can still come forward and fight.