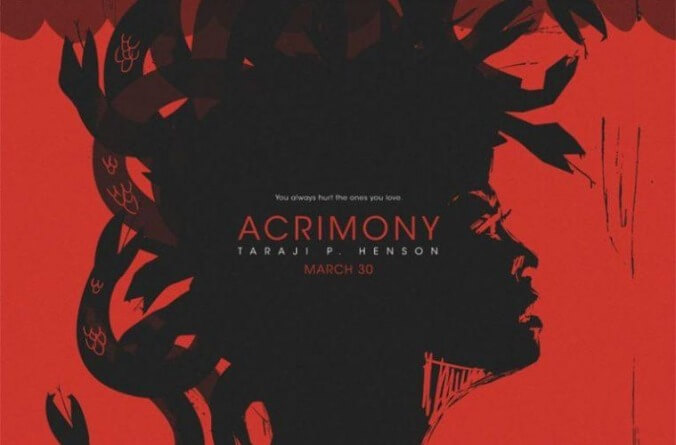

The First Wives Club meets Fatal Attraction in Tyler Perry's overwrought Acrimony

“Every time a black woman gets angry, she’s a stereotype.” This statement is spat out early on in Tyler Perry’s Acrimony by Taraji P. Henson, as she lights up a cigarette in her court-ordered anger management therapist’s office. (She doesn’t ask first. She just does it.) Henson, appearing in her third film with Acrimony’s eponymous writer, director, and producer, has an intensity about her that gets her cast in many variations on the “vengeful woman” theme, whether it be the righteous protector (Proud Mary) or sassy queen bee (Empire). Here, she goes from bunny-boiling psycho to martyred wife and back again as Melinda, a put-upon fortysomething who is pushed over the edge when her ex-husband Robert (Lyriq Bent) strikes it rich and gets engaged to another woman, the poised, successful Diana (Crystle Stewart)

Whether Perry is an inspiring example of a black filmmaker finding success outside the studio system or a damaging perpetrator of black stereotypes (or both) has long been a subject of debate, particularly within the African-American critical community. (For more on this particular subject, see writers like The A.V. Club’s Joshua Alston, who criticized white critics’ reluctance to engage with Perry in 2013; Rembert Browne, who discussed the controversy with Perry himself in a lengthy profile for Vulture in 2015; and Jacqueline Coley, who reflected on Perry’s career ahead of Acrimony’s release for IndieWire this week.) Most critics agree that his movies aren’t very good, making them predictable punching bags trashed by everyone from The New York Times to the Razzie Awards.

And it is true that there are certain formal aspects of filmmaking that Perry, who’s directed dozens of films and even more TV episodes, really should have mastered by now. The composition of Acrimony is awkwardly theatrical, the dialogue similarly ungainly, and the structure of the film is more unstable than the late stages of a Jenga game: How could Melinda remember conversations for which she wasn’t present, for example? Perry even uses that old crutch of the college freshman with an imminent deadline, splashing the movie’s themes along with their dictionary definitions—“Acrimony: bitterness, anger, rancor, resentment, ill feeling…”—up onto the screen as informal chapter markers. None of it makes sense for a director several decades into his career, unless you account for the possibility that Tyler Perry doesn’t care all that much about mise en scene and three-act story structure. So, then, what does he care about?

What he cares about in Acrimony is a morality tale, as muddled as it may be. Smushed somewhere in there between the righteous indignation of Henson’s opening monologue and the deliriously over-the-top ending lies a lesson on the virtues of patience, trust, and gratitude, none of which Melinda displays in her relationship with Robert, as much as she protests to the contrary. Robert is no saint, either; he freely spends Melinda’s middle-class inheritance, forcing her to work two jobs while he sits at home tinkering with a self-charging battery whose mechanics are never really explained. (Not that it matters.) As the plot unfolds, we start to wonder if Robert might not actually be such a bad guy. He’s certainly not the monster Melinda makes him out to be—which only confuses things further, given that the story is ostensibly told from her perspective. The only ones with any sort of consistent worldview are Melinda’s sisters June (Jazmyn Simon) and Brenda (Ptosha Storey), the Greek chorus of the story whose refrain of “men are trash” remains clear throughout.

It’s implied throughout—and once explicitly mentioned—that Melinda has some sort of personality disorder. She describes it as akin to Dexter’s “dark passenger,” a disembodied, blind fury that takes control of her when she gets angry and makes her do crazy things. Perry visualizes Melinda’s disturbed psyche in hilariously hackneyed ways, like having her repeatedly ram Robert’s RV with her car when she suspects he’s cheating on her or literally stick knives through photos of her hated ex. He also writes her fury into the script in deliciously campy dialogue like, “men don’t have a why, they just have a bunch of lies” and “you know I can be the motherfucking devil,” the latter of which Henson delivers with all the narrow-eyed vitriol you could ever ask for in a vengeful leading lady. You can practically hear the drag queens preparing their impressions in the background.

So what was Tyler Perry going for here? Based on the sanctimonious streak that runs throughout his work, one might posit that he was trying to wrap a gleefully outrageous thriller around a lesson on marriage, like a slice of bacon around a particularly bitter pill. Except, at some point, the bacon got hopelessly overcooked.