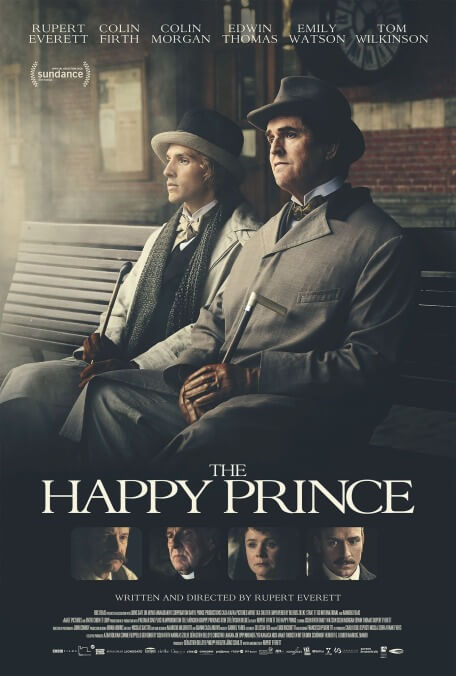

The fountain of wit dries up in The Happy Prince, an Oscar Wilde biopic about his sad last days

As a general rule, biopics fare better when they focus on a relatively thin sliver of the subject’s life, rather than chronicling everything from cradle to grave. And there’s nothing wrong with avoiding a celebrated figure’s glory years in order to explore less familiar biographical terrain. The Happy Prince, however, takes this theoretically admirable notion much too far. Apart from a few quick flashbacks, the film skips past not only Oscar Wilde’s literary triumphs, but even his conviction on charges of “gross indecency” and the two years he spent in prison. Instead, Rupert Everett—who directed, wrote the screenplay, and plays Wilde himself—exclusively depicts the author’s deeply depressing final years, which were spent as an impoverished pariah in perpetually ill health. This approach maximizes the empathy one feels for Wilde, who was a victim of Victorian animus against homosexuality, but at the expense of devoting nearly two hours to a period during which he did nothing of any interest except suffer and die.

Indeed, it’s difficult to describe The Happy Prince (titled, with sad irony, after one of Wilde’s short stories written for children; he spent these last years separated from his own two sons) without just compiling a list of the people who were still willing to associate with the disgraced man. First and foremost, there was Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas (Colin Morgan), the young aristocrat whose father, the Marquess Of Queensberry, Wilde had sued for libel, leading to his own subsequent arrest. (Again, none of this intrigue is in the movie, except as occasionally referenced in dialogue; Everett assumes audiences know the background.) Bosie remains loyal to Wilde for a short time, financing what amounts to a rather bleak, low-rent holiday, but ends the relationship when his family threatens to cut him off financially. More steadfast are Robert Ross (Edwin Thomas), Wilde’s literary executor, and Reggie Turner (Colin Firth), a close friend who was at Wilde’s bedside when he passed away from meningitis in late 1900. Their devotion is touching, but not especially dramatic; neither one ever quite coalesces as a distinct character.

Mostly, The Happy Prince serves as an opportunity for Everett—who starred in screen adaptations of Wilde’s An Ideal Husband and The Importance Of Being Earnest (opposite Firth again in the latter), and previously played Wilde onstage in a revival of David Hare’s The Judas Kiss—to inhabit the melancholy side of a renowned wit. At 59, the actor is now 13 years older than Wilde lived to be, yet still appears to have been artificially aged (and fattened) into the role; his performance attempts a tricky amalgam of sardonic and lugubrious, which too often crosses the line into maudlin martyrdom. His screenplay, meanwhile, tries to compensate for a lack of incident or psychological acuity, plus the absence of Wilde’s best-known accomplishments, by repurposing some of his plays’ most quotable lines (e.g., the definition of a cynic as someone who “knows the price of everything and the value of nothing,” from Lady Windermere’s Fan), allowing knowledgable viewers to nod at the allusion. Despite its undercurrent of anger at Wilde’s mistreatment by fashionable English society, the film feels like a vanity production—and Everett clearly fears that it may be perceived that way, as he opts to bill himself fifth (non-alphabetically) in the cast, despite appearing in almost every shot. Such false modesty ill suits a flamboyant legend like Oscar Wilde, even in a perverse account of his slow fade to black.