After 47 years of making documentaries, Frederick Wiseman has his methodology down pretty darn pat, for better or worse (usually better). Odds are the most challenging aspect of his professional life is simply deciding what milieu or institution merits his detached yet penetrating gaze next. Lately, Wiseman’s been on an artistic kick, making films about Parisian ballet (La Danse) and burlesque (Crazy Horse) alongside his more trenchant efforts (last year’s epic At Berkeley). National Gallery, filmed at the titular London museum, is another entry in that vein, providing a cinematic tour of numerous masterpieces along with fascinating glimpses of what goes on behind the scenes. At nearly three hours, it can be a trifle exhausting, but then, so can an actual visit to a museum. And while the National Gallery has many superb guides (several of whom appear in this film), none can offer the free-ranging access that Wiseman does here.

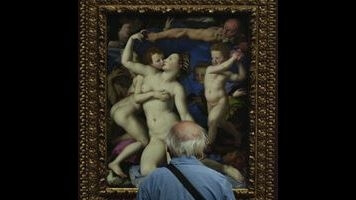

As always, there are no direct-to-camera interviews, no expository title cards, no efforts of any kind at contextualization. Anyone who doesn’t already know the National Gallery ranks fourth among the most visited museums worldwide (trailing only the Louvre, the British Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum Of Art), won’t be fed that information by Wiseman. Instead, he plonks his stationary camera down in various rooms and galleries and just observes what unfolds. The least interesting sections tend to be those that focus on the artwork itself—which is to say, on what you could see just by showing up at the museum on your own. Several times, the film watches for minutes as a docent tells a group of students, tourists, or kids all about a particular painting, explicating its history and pointing out notable aesthetic details. These are knowledgeable, engaging speakers, but similar videos can be found on the museum’s website.

Far more compelling are Wiseman’s peeks into the areas ordinary visitors to the National Gallery never see. One early highlight is a candid conversation among staff members regarding the delicate balancing act involved in marketing the museum and its collections, with some wanting to aggressively court people who don’t necessarily think of themselves as art lovers while others worry about tarnishing a sophisticated public image. Better still, and arguably worthy of a documentary all to itself, is time spent with director of conservation Larry Keith, who reveals the painstaking work involved in restoring centuries-old paintings to a state closer to their original glory. Rembrandt’s Portrait Of Frederick Rihel On Horseback, for example, was discovered upon X-ray inspection to have been painted on top of another composition entirely—one that was horizontal rather than vertical. Aspects of the original painting were beginning to “bleed” through the final work, requiring delicate intervention.

Unlike Wiseman’s greatest films, National Gallery never quite finds an overarching theme. There’s a fair amount of material regarding the art/commerce divide, but many scenes have no bearing whatsoever on that subject, and the film generally lacks urgency. Wiseman is at his best when he’s capturing the ugly collision of regular folks and the system, having beaten The Wire to that approach by several decades. His cultural-institution pictures, by contrast, feel like his means of relaxing a bit, of working without having to experience the sort of constant tension inspired by a hospital (Hospital) or a welfare office (Welfare). When it comes to a towering master like Wiseman, however, even the minor efforts are pretty major.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.