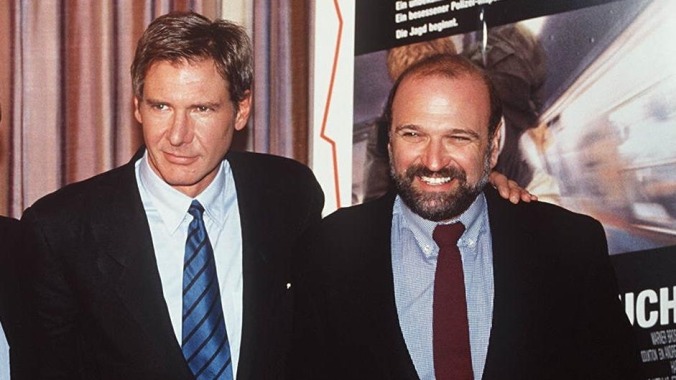

The Fugitive at 30: Director Andrew Davis on "Harrison Ford's best performance"

Davis also talks about how Ford continued filming despite injuries, and why he wasn't involved in that U.S. Marshals sequel

Director Andrew Davis has plenty of films to his credit, including the massive family hit Holes and the highly regarded Michael Douglas thriller A Perfect Murder, but he’s more than happy to mostly be known as “the guy who directed The Fugitive.” And no wonder. The action-thriller starring Harrison Ford and Tommy Lee Jones grossed $369 million at the worldwide box office and notched seven Oscar nominations, including Best Picture (Jones took home the film’s only statuette, in the Best Supporting Actor category.)

The Fugitive, which was released on August 6, 1993, holds up remarkably well three decades later. Ford plays Dr. Richard Kimble, a man wrongly accused of murdering his wife, who tries to prove his innocence before he can be captured by the ferocious and unsympathetic Deputy U.S. Marshal Sam Gerard (Jones) and his team. Davis’ film benefits from a smart story, terrific pacing, top-notch performances from Ford, Jones, Joe Pantoliano, Sela Ward, Andreas Katsulas, and Jeroen Krabbe, visceral practical stunts, and a riveting James Newton Howard score.

Davis agreed to spend a half-hour chatting with The A.V. Club via Zoom from his home in Santa Barbara, California, as The Fugitive marks its 30th anniversary. During that extensive conversation, he reflected on his experience making the film, its legacy, and an upcoming release of a restoration print, as well as several new projects he has in the works.

The A.V. Club: Roy Huggins, creator of The Fugitive television series, gave you what you consider the movie’s best review. What did he say?

Andrew Davis: He said he thought the film was fantastic and that I’d done a great job. It was in the trades, and it was really wonderful.

AVC: How surreal is it to you that we’re talking about this film 30 years later?

AD: How surreal is it? Well, you know, it became such a part of who I am. “Who is he?” “Oh, he directed The Fugitive.” I’m always referred to as “the guy who directed The Fugitive.” Now, to the next generation, I’m “the guy who directed Holes.” But, it was a great experience, the kind you’d like to recreate in terms of the creativity and the people I was working with. I don’t know. It just changed my life. Put it that way.

AVC: You’ve been watching the film a lot lately as you prepare for a restoration print. How well do you think it’s aged?

AD: It’s more timely than ever. It’s about pharmaceutical companies and greed and injustice. What else can be more timely than that today?

AVC: Preparing to shoot The Fugitive, you chose not to binge episodes of the old series. Why?

AD: There had been many other writers who had been working on this thing. I was handed a script that made no sense at all. I figured, “Well, OK, the guy is accused of killing his wife. He didn’t do it. He’s on the run. There’s a train crash. Let’s figure out how to make an interesting thriller out of this. Just start from scratch and try to figure out how to make it make sense.” There were certain elements that David Twohy put in there, with the jumping off the dam and things like that. But the dialogue made no sense and the characters made no sense. Once we got into this pharmaceutical conspiracy—and I was from Chicago, Harrison’s from Chicago—we could easily craft a world of a doctor who had been in this environment. We just went on our instincts about what was logical and what was emotionally involving, and went from there. There were certain ingredients we were handed, but then they all had to be woven together and then we had to create a whole spine for the motivation of why they were after him.

AVC: So, the show itself would have been of no value to you …

AD: It may have been a value, but I was so busy. I’d just finished Under Siege, and I literally went from the premiere of Under Siege into pre-production on The Fugitive. I wasn’t sitting down and watching … I think it was North By Northwest, a little bit, later, actually. I think after we finished it, I watched it again. But I was just trying to make a thriller that was in the world that I liked of Sidney Lumet and Bill Friedkin, those kinds of filmmakers.

AVC: I consider Harrison Ford’s performance to be one of his best, really relatable, very emotional. I didn’t know he had that in him. Did you? And how did you help him get there?

AD: You create an environment that has a reality to it. He’s not a dumb guy. He understood what it meant to be an arrogant doctor. It just rubbed off. The marshals worked with Tommy Lee and those guys, and we got things from them. We met a real doctor in Chicago, whose house we copied. It was not hard at all. I think it is one of his best performances. I really do. I didn’t have to say, “No, Harrison. Say the line this way.” There was never any kind of thing like that. There was a tone and an attitude, and we all sort of understood what the level of reality had to be.

In terms of his own emotional acting … there’s the scene in the beginning where he breaks down. He’s been accused by the cops, and then there’s the interrogation. He had a requirement that he couldn’t work over so many hours in terms of his workday, and he had already been sent back to go home for the night. I was going to do the coverage of the cops without him. The script supervisor would read his lines offscreen. He heard that we were still shooting, and he came back to the set and said, “I want to be there to play offscreen for these guys.” I don’t remember if that one great shot, where it pushes in on him crying, was done because of that or if we had done that already. I think that it happened because of the symmetry of everybody being together. And the two guys interrogating him, one was a real cop and the other was a guy who had been imprisoned for killing a cop. So, there was a reality to the world we were living in and then Harrison was smart enough and capable enough as an actor to live in that world. He helped create that world.

AVC: Was it the same thing with Tommy Lee Jones?

AD: Well, he picked up on certain things from these marshals. It wasn’t about right or wrong. His job was just to bring him in, right? “I don’t care. You know, it’s not my job. Let the Justice Department decide that. Let the prosecutors decide that.” He’s just incredibly smart and creative. We had just done Under Siege together. I’d done The Package with him before. He’s a very capable, smart guy.

AVC: When Ford got hurt in North Carolina, did you think, “We’re screwed” or “Hey, this could actually work for the character”?

AD: I didn’t realize how serious it was. He’s hurt himself a lot in movies. He’s twisted ankles and gotten banged around, things like that. It didn’t really jump out to me until the City Hall sequence, when he’s running through City Hall, and being chased by Tommy Lee. You see him limping off, and that’s real. That’s a real limp, but it didn’t affect the production at all.

AVC: Tell me a battle with the studio that you won and a battle that you lost.

AD: I don’t really remember any battles. It’s very complicated. There was a documentary where it said, “Well, Andy didn’t want to do the sequence because Tommy is shooting and Harrison had the power to overrule him …” What happened was Tommy did not want to do the sequence. Tommy said, “I would not be shooting in public, in a place like this, right? It would be very dangerous and endanger innocent people.” And he was right. Then, it’s interesting because in the (recent Rolling Stone oral history) article, (co-writer) Jeb Stuart revealed something I thought was very smart. He says, “Listen, Tommy, you just shot point blank at an African American guy in a house and dropped him down, but you’re not going to shoot at Richard Kimble?” Now, the difference is he had one of his marshals in his grip. He was endangering one of the marshals, and so that justifies shooting. But there was one moment that was sort of delicate for me in terms of trying to negotiate between what the script said, what the producers wanted, what Harrison wanted, what Tommy was (after). I felt conflicted because both of them had interesting points of view. But the sequence works.

AVC: The initial cut of the film ran 3 hours and 10 minutes. Was that due to the script being unfinished when you started to roll camera? Why a 190-minute first cut?

AD: No. There was a sequence where Harrison buys hair dye. We didn’t need that. Also, I shoot a lot of footage. If you look at the film, how many minutes are montages? James Newton Howard’s score is just soaring above it. When we remixed it, I was blown away by how good the music is, and how it just it’s a visual symphony. We could have expanded some of that more or compressed it down. The St. Patrick’s Day parade could have been a minute or two longer or shorter. There are certain things that are like an accordion. You could do this with it. So, it wasn’t like we dropped a lot of sequences, but there were some. That’s usually the case. You put something together and the editors … It’s called shoe leather. To get from A to B, you don’t need to have all the walking to get from this place to that place. You just cut right inside. But then there are certain sequences where they’re all walking and talking, and it’s some of the best stuff in the movie. When they’re coming out of the One-Armed Man’s and Tommy’s telling them, “Go to this, go to that,” you could have taken all that out.

AVC: In other words, you wanted to shoot so you had it. It could be taken out if necessary, but if you didn’t shoot it, you’d never have had it …

AD: Oh, yeah. I mean, the editors have never complained about having too much footage.

AVC: If you made the movie today, what do you think you would have to do differently?

AD: Well, who would play Tommy’s part? Who would play Harrison’s part? I don’t know who that would be today. I wouldn’t want to do a digital train crash, that’s for sure. What’s great about the train crash is not so much the train crash, it’s the day after, when they’re walking around and the thing is laying there as a remembrance of what happened. And the aerials, where you see it, you go, “Oh, my God, it really happened.”

AVC: Ford, Jones, and Joey Pantoliano all initially thought they were making a bomb—a movie that would ruin their careers. They didn’t want it on their resumes. What did you think?

AD: James Newton Howard came to see me about three weeks into shooting. The editors had assembled some material. We sat in my hotel room, the Four Seasons, and we watched it together. I’d worked with James earlier on The Package. We’re sitting there watching it and I realized that there was a connection and empathy and sympathy that you were going to have about Harrison that could track and work for grandmothers and grandchildren. (I realized) that it had a really broad base kind of quality to it, that it could appeal to lots of people. You cared about this guy. You cared about this situation he was in. You cared that he loved his wife. Also, I’ve made about six movies in Chicago, and I was able to use the city as a character. I had my crew. I had this great cast to work with. Everybody was going, “What’s happening? What’s happening? What’s happening?” I was just sort of like, “I know what I have to accomplish every day.” I just did my thing. I was lucky. I was coming off a big hit with Under Siege. I guess I was arrogant. I don’t know.

AVC: Did you want to do the sequel, or were you happy to have nothing to do with U.S. Marshals?

AD: I’m trying to remember the dynamics. We were already making A Perfect Murder. The same producer did both. I don’t know what the logistics were, but I remember we had dinner in New York. We were with Michael Douglas and Viggo (Mortensen) and Gwyneth Paltrow making that movie. Peter MacGregor-Scott was with me. The crew of The Fugitive went on to A Perfect Murder, a lot of them; the camera crew and some of the other people. The art department went on to Marshals. But we had dinner with Robert Downey Jr. and Joey Pants and Tommy Lee. I don’t know. I guess it was something they were doing. I was sort of interested. Maybe I would have enjoyed doing it. I know Tommy wasn’t very happy to be doing that movie.

AVC: Did you worry at all about U.S. Marshals hurting the reputation of The Fugitive? Or is that just business as usual because a hit will beget a sequel?

AD: You know what? Harrison is such an important part of The Fugitive. He wasn’t in [U.S. Marshals], so it was a different thing. I was proud of A Perfect Murder, and it didn’t affect me in terms of that. Listen, they tried to do a TV series. That didn’t work. They tried to do that thing [Quibi shorts] with Katzenberg. They tried several times to recreate this thing. They tried it with Kiefer Sutherland. They tried it with this guy. I don’t know why they don’t work, but I was lucky. I was able to find the right Stu.

AVC: You’re involved with a restoration of The Fugitive. What is being restored?

AD: All we’re doing is remixing. It’s a really great story. Frank Montano was a 27-year-old mixer. He was doing sound effects with Don Mitchell, who was the top dialogue mixer at the time. He sat next to him, and we did Under Siege together. He got nominated for an Academy Award the first time he worked with Don Mitchell. He went right into The Fugitive and he got nominated again. So, when he found out that Warners was going to restore it, he called me up and said, “Andy, you’ve got to let me do this. I’m the one who knows how it should sound. I was there. I don’t want anybody to screw this up.” And he had a relationship with the people at Warner, at sound. It turns out Frankie now is the top mixer at Universal. They tore down a shooting stage and built a dubbing stage for him. He just remastered Jaws and Back To The Future. He got them to give him the masters (of The Fugitive). I played a role in that, but I said, “Let Frankie do it.”

So, I went to listen. He’d cleaned it up. The first time I heard it, I go, “Frankie, something’s wrong. It sounds so clear. You’ve got to put some more street noise in there because everything’s so clear.” I wasn’t used to that, you know? And hearing the score in Atmos was amazing. Then, I went over to Warners, and a guy named Jan did the restoration of the picture. He basically re-scanned the negative in 4K, and I worked with him very closely. He just made it look beautiful and was able to make it so clean and crisp. He was able to do everything I wanted to do, which I couldn’t do back then. In the old days, all you could do was make it brighter, darker, bluer, or redder.

AVC: What’s the plan for the restoration? Will there be screenings, a Blu-ray, and a theatrical re-rerelease?

AD: There’s a screening on August 19th at the Aero Theatre (in Los Angeles). The American Cinematheque is sponsoring it. It’s delicate because of the strike. We’re not going to do any promotion. We’re just going to show up and they’ll ask me some questions. A lot of the cast is coming and the crew are going to be there. And then they say they’re going to release it in the fall in selected theaters around the country, and then I think they’ll release it on Blu-ray later this year.

AVC: Your most recent film, The Guardian, opened back in 2006. Why have we not seen more films from you? And, are you working on anything now?

AD: I just got a deal on a novel I wrote that is going to be published and will hopefully be a movie someday. It’s called Disturbing The Bones, a political thriller set in Illinois in Chicago. I’m very excited about that. I worked on it with a writer named Jeff Biggers. I just got the rights to a Gene Wilder book called My French Whore, a World War I sort of spoof set. I’m trying to get a project going I’ve been working on for a long time, a remake, a modern version of Treasure Island called Silver’s Gold. I’m working with Cary Brokaw on that. There’s some interest in some financing in that. I need to put the cast together.

What else? We just had a 20th-anniversary screening of Holes. A thousand people showed up to watch that in L.A., outside at night. And my movie Stony Island, my first film, is being re-released. You can find that on my website. That’s a very exciting thing. And why haven’t I worked more? I didn’t want to do stupid action movies. I was offered a lot of really bad action movies, and I didn’t want violence to become part of what I was doing. After Holes it was like, I’d rather make family films, make films based on good literature. And I think I was an expensive guy who had a lot of creative control. And I didn’t want to do comic books. I never read comic books as a kid. Also, I had a lot of personal stuff. I’ve married two kids. I buried two parents. I had grandchildren and dealt with some health issues in the family. So, that’s what I’ve been doing.