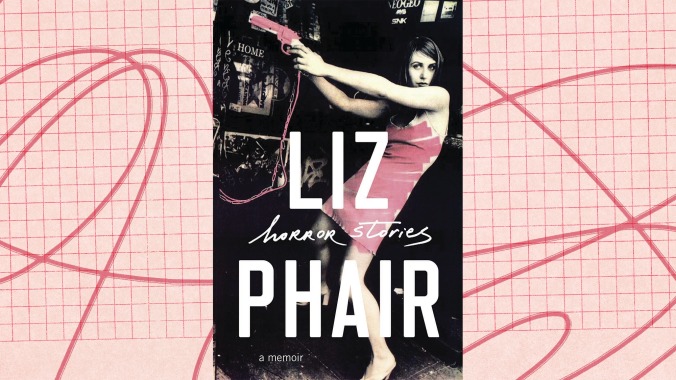

The ghosts and monsters are all internal in Liz Phair’s Horror Stories

Although the lyrics to her songs chart her inner world in intense topographical detail, Liz Phair tends to leave names out of it. Even her famously confessional 1993 debut, Exile In Guyville, drapes its righteous kiss-offs in coy first-name-basis storytelling, leaving listeners to speculate for themselves who the songs are “really” about. The same holds true for Phair’s new memoir, Horror Stories, which indulges in just one casual rock ’n’ roll name drop: The time Phair ran into Dandy Warhols singer Courtney Taylor-Taylor on the street during the Northeast blackout of 2003. The rest are obscured, though easy enough to figure out if you’re motivated to do so. Husbands, boyfriends, and secret lovers (as well as Phair’s truest love: her son, Nick) are referred to by their first names, while acquaintances are sketched as music-industry archetypes: The photographer. The producer. The promoter. The executive.

That’s not to say that the book isn’t intimate. Horror Stories is structured around the moments of anxiety, discomfort, indecision, humiliation, and regret that have defined Phair as a person, illuminating specific memories with the vivid flashbulb of her famous wit. Perhaps it’s for this reason that the book only tangentially mentions Phair’s scrappy early years as an unknown singer-songwriter in Chicago’s once hip Wicker Park neighborhood; as she says in the lead-up to a story about visiting her grandmother in a nursing home around that time, things were going well for her. Not a lot of psychic manure to compost into hard-won wisdom there.

Horror Stories jumps around from Phair’s early childhood to earlier this year, recounting events that range from a split-second epiphany to a years-long decline. She recalls a young woman she and her friends left passed out next to a toilet their freshman year of college, and wonders if she made it home safe or choked to death on her own vomit. She tells the story of the time she performed at a live radio concert with severe laryngitis, and how it made her realize that “I fought my whole life to have a voice, both literally and figuratively. If I stay in this radio realm, I’m not sure I need one.” Each of these stories has a complete narrative arc, with a beginning, middle, and end. Sometimes they even have punch lines. But the result is less a complete chronicle of Phair’s life than a road map to her vulnerabilities.

The rawest chapter in the book is entitled “Hashtag,” and uses the New York Times exposé of Ryan Adams (unnamed, but with details that point directly at him) as an in for not only Phair’s experiences with him—surprise, surprise, he was threatened by her confidence—but also the litany of violations she’s been subjected to over the years for having the audacity to exist in the world in a female body. Some of these things happened after she became famous, and some of them happened before. And Phair approaches the #MeToo movement with clearer eyes and a more compassionate attitude than some of the women in the generation before her, refusing to blame the victim and writing that “I learned from a young age that just because you don’t see the behavior doesn’t mean it isn’t happening.” She’s honest about her fear that even now, 26 years after Guyville, speaking up might ruin her career.

This honesty isn’t always flattering, in big and small ways. (Perhaps the most self-deprecating story in the book is about Phair getting way too invested in flirting with a cashier at Trader Joe’s.) Phair knows there’s no redeeming her behavior during the affair that ended her marriage—“I hate how much pain I caused everybody,” she writes—but she digs into it anyway. She realizes that believing in God isn’t popular among the bohemian set, but she has had too many moments of clarity not to share them. Overall, Phair comes across as a restless person who doesn’t feel wholly at home anywhere, and self-destructs when things get too comfortable. She also comes across as extremely self-aware, with the exception of a chapter where she reveals, but doesn’t really interrogate, her own white privilege when talking about a break-in at her college apartment.

But while Phair’s Horror Stories are often painfully relatable, the combination of blunt emotional truth and lyrical prose doesn’t always meld. Sometimes her poetic musings are downright profound, as when she gets lost in a blizzard and becomes acutely aware of the primitive survival instincts that flow through her blood. Other times, her dry humor doesn’t translate to the page, as when she rattles off a half-dozen cutesy euphemisms for “vagina” in the chapter about childbirth. (She does call it a “blind albino cave salamander,” so it’s probably safe to err on the side of sarcasm. But it’s a confusing journey nonetheless.) Still, Phair’s been everywhere and done everything, including some things she’s not very proud of. If she wants to indulge herself a little, now that she’s looking back on all of it, well, she’s earned it.