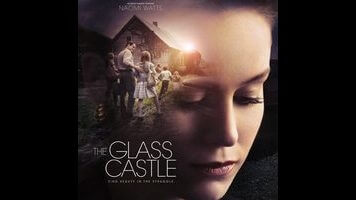

The Glass Castle takes a gritty true story and spins it into Hollywood fluff

Jeannette Walls, the author of the best-selling 2005 memoir whose big-screen retelling hits theaters this week, reportedly played a consulting role in the production of The Glass Castle. Walls, whose book casts a non-judgmental eye on an upbringing that might kindly be referred to as “unconventional” and less kindly as “neglectful,” writes in the Los Angeles Times that she was pleased with director Destin Daniel Cretton and star Brie Larson’s attention to detail in adapting her story into a film. While it’s understandable that Walls might not want to linger on the more grim aspects of her childhood, Cretton’s decision to pull punches on those exact moments takes what could be a powerful tale of resilience and forgiveness and spins it into just another piece of Hollywood feel-good fluff.

Cretton, who made a name for himself alongside Larson with the festival favorite Short Term 12 (2013), does show an eye for period detail, both in the section of the film that takes place in late ’80s New York, where an adult Jeannette (Larson) has rejected her parents’ bohemian ideals and works as a gossip columnist, and in extended flashbacks to her nomadic 1960s childhood. We open with an elementary-school-aged Jeannette landing in the hospital after lighting her dress on fire cooking lunch; her mom, Rose Mary (Naomi Watts), was home at the time, but couldn’t be bothered to make food for her daughter when she could paint instead. Rose Mary, who’s described in the book as a woman uninterested in domesticity or the responsibility of raising children, is a peripheral figure in the film, with little insight into her mind-set beyond the basic fact that she’s an artist. Jeannette’s three siblings are similarly streamlined and sidelined, showing up to lend support (or a plot point) when the narrative requires them to.

Instead, the film focuses almost exclusively on the relationship between Jeannette and her father, Rex (Woody Harrelson), a brilliant, stubborn, anti-authoritarian alcoholic who constantly moves the family around in pursuit of some ill-defined romantic ideal of freedom. As Jeannette grows older and begins to realize that sleeping in cars and on floors isn’t a fun adventure, it’s homelessness, the film’s tone shifts and we start to see the uglier side of Rex and Rose Mary’s parenting strategy. Even after the Walls settle down in a shack with no electricity or running water in Rex’s poverty-stricken West Virginia hometown, the parents routinely forget to buy food for their children and neglect to enroll them in school, forcing the siblings to take care of these basic necessities themselves. At one point, Rex gives up drinking for a while and gets a steady job, and things seem to finally be stabilizing. That doesn’t last long, though, after a visit to Rex’s parents reveals a troubling pattern of abuse in the Walls family.

That last detail, which is strongly implied to have led Rex down his troubled path in life, is barely discussed in the film. And while it’s impossible to completely gloss over the destructive nature of Rex’s alcoholism, The Glass Castle is far more eager to give Harrelson a passionate monologue on how the edge of a flame represents the chaos of the universe, or how you can’t touch a star but you can claim one as your own, than to dig deep into emotional ugliness. Some of Rex’s whimsical life lessons are downright on the nose, like a scene where he repeatedly throws young Jeannette into a swimming pool until she figures out how to swim. (Granted, if that’s how it happened in real life, that one’s on Rex Walls.)

That’s not to say that a two-hour-plus trudge through poverty and addiction would necessarily be preferable to inspirational hokum, or that Wells is wrong for remembering her father’s bright side as well as the darkness in him while writing her source material. But it doesn’t help that the filmmaking choices throughout The Glass Castle default to cliché: the paint-by-numbers stirring score, for example, or the use of slow motion to indicate where you’re supposed to get choked up. With a talented cast that’s perfectly capable of conveying emotion without the use of cheap sentiment—Larson is sensitive as always in her portrayal of the adult Jeannette, and Harrelson equally fascinating in depicting Rex as a wild-eyed dreamer and hostile drunk—these tricks and narrative contrivances really aren’t necessary. Like little Jeannette and her siblings, this cast deserves better.