The good and the bad of Aaron Sorkin are on full display in his directorial debut, Molly's Game

When highly successful Hollywood screenwriters suddenly decide to direct, they generally do so out of a desire to protect their vision. That can hardly be the case with Aaron Sorkin. Whether his scripts have been interpreted by Rob Reiner (A Few Good Men, The American President), David Fincher (The Social Network), or Danny Boyle (Steve Jobs), the resulting movies are always unmistakably his babies; it’s tough to imagine even more Sorkin-inflected versions that might have been. (Maybe characters would unexpectedly answer questions they’d been asked 10 minutes and 50 lines of dialogue ago, rather than only three minutes and 20 lines ago?) Whatever his reason may be, after 25 years in the business, Sorkin has finally stepped directly behind the camera for Molly’s Game, his adaptation of Molly Bloom’s memoir about her days running ridiculously high-stakes underground poker games in Hollywood and New York. Turns out pure, unmediated Aaron Sorkin is almost indistinguishable from the auteur-driven variety.

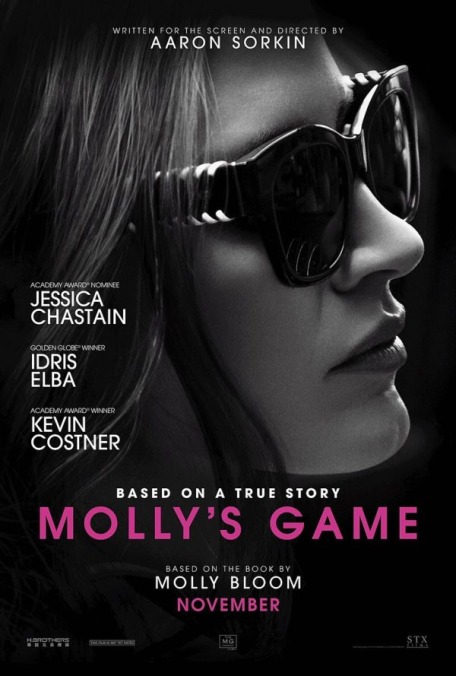

Molly’s Game does provide him with his first female protagonist, the fearsomely intelligent, maddeningly loquacious, and self-destructively driven Molly (Jessica Chastain), a character who recalls the Sorkinized Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg. She kicks the movie off by narrating her entire early life at blistering speed, tracing the circuitous route by which a former Olympic-hopeful skier wound up hosting an assortment of movie stars, musicians, and business tycoons around a poker table. (Minimum buy-in: $10,000.) Half of the film depicts her gradual rise, in flashback, as she locks horns with one particularly demanding actor (Michael Cera, whose real-life counterpart is never identified on screen, but who insiders will know is playing Tobey Maguire) and gradually gets mixed up with both drugs and the Russian mob. The other half follows the efforts of her attorney, Charlie Jaffey (Idris Elba), to arrange a deal with the Feds who eventually arrest her—one that won’t compel her to reveal the identities of the famous players.

Unlike Rounders, the only previous notable movie about underground poker, Molly’s Game isn’t much interested in the intricacies of expert cardplay. One superb sequence accurately captures the experience of going “on tilt”: losing a big hand due to bad luck, then attempting to recover the loss quickly via reckless, out-of-character gambling. For the most part, however, Sorkin concentrates on the tricky dynamic between the players and Molly, whose job requires her to maintain an impossibly perfect balance between intimidation and seduction. Highly entertaining sparks also fly between Molly and Charlie, though the film’s big ethical dilemma—should Molly sell out a few celebrities, potentially harming their reputations, in order to avoid a harsh prison sentence?—doesn’t exactly get pulses racing. The film’s energy derives from its portrait of obscenely wealthy people throwing money around, scarcely aware of how many bills Molly pockets in return for engineering a fantasy world catering to their every need.

Also from the dialogue, of course. It’s a pleasure listening to Chastain spit out Sorkin’s trademark torrents of implausibly wised-up verbiage, and fascinating to watch Elba put a more laid-back spin on the words. As a director, Sorkin mostly (and wisely) stays out of the way of his screenplay, composing shots with an eye toward how they’ll likely be shaped in the editing room, based primarily on verbal rhythms. It’s solid, professional work, intent on ensuring that the story zips along with few speed bumps. When Molly’s Game does falter, ironically, it’s due to lousy, Newsroom-level writing. No filmmaker, however talented and experienced, could have salvaged the movie’s worst scene, in which Molly’s father (Kevin Costner), a therapist, shows up out of nowhere and proceeds to psychoanalyze her at length, explaining her drive to dominate as latent daddy issues and apologizing for his unwitting role in her downfall. Maybe another director would have lobbied to have that scene removed? Probably not. The same fundamental strengths and weaknesses—the former usually outweighing the latter, happily—are evident in all of his movies, no matter who’s in charge. A master like Fincher can add some visual zing, but the song remains the same.