“Whatever happens, it’s cool my babies, it’s very cool.”

Or so you’d think, right?

After all, two trashbags, a dilettante, the most indecisive nerd in the universe, a sexy Alexa, and a reformed fire squid demon have sussed out every trap and loophole the universe could throw at them, broken every immutable cosmic rule in pursuit of justice, traveled back in time, resisted the lure of an omnipotent Judge’s hand-tailored tests, and stormed the demonically drab halls of hell in order to, finally and for real this time, make it to the Good Place. (Plus, the humans are all dead, for added difficulty.) The show ends (with a two-parter) next week, creator Michael Schur and company have all packed up shop for good, and the whole improbable, deliriously silly, heart-wrenchingly complex story will end. For good, with our heroes—having received special dispensation to enter eternal paradise since they corrected the seriously forked-up balance of right and wrong in all of creation—linking arms and striding triumphantly into the welcome party that is their much-deserved entrance into their just reward.

Only, paradise is broken, just like every other damned thing in this universe.

The “Patty” of the episode’s title refers to the storied mathematician, thinker, and so-dubbed “martyr of philosophy” (she got horrifically mutilated and murdered by a mob around 415 AD) Hypatia of Alexandria. And in keeping with Jameela Jamil’s hints about the final few episodes of The Good Place being filled with cameos from NBC royalty, she’s played by former Friend Lisa Kudrow as a, yes, friendly, welcoming, and expectedly quirky resident of the Good Place. Like, really quirky. Too quirky. Alarmingly quirky. As she puts it to a puzzled Eleanor and Chidi soon after meeting the pair at their four-way welcoming mashup party, life in the Good Place has turned this legendary intellect, along with her similarly accomplished and noble colleagues, into a “glassy-eyed mush-person.” “No! ‘Cause, Patty, no!,” moans Chidi at the news, delivered over some of the Good Place’s signature stardust milkshakes, and we’re right there with him. Like every other would-be incremental victory in Team Cockroach’s valiantly bumbling journey toward salvation (or at least an eternity devoid of butthole spiders), this seemingly final victory is snatched away.

It’s the sort of soul-crusher of a disappointment that would take down even the stoutest heroes, but, then, those heroes don’t have our heroes’ experience in discovering the myriad, truly unimaginable ways the supposedly ordered universe is actually a rickety bureaucratic nightmare of mundane cruelty and lazy problem-solving. So, faced with this most existentially horrifying of blows, they set out to fix heaven. And they do.

The Good Place, like its heroes, has set itself a monumental, unthinkably audacious task from the beginning. Examining the whole of human thought about good and evil, gods and devils, and the eternity that comes after death and saying, “Nope, we can do better” is, as Jason might put it, a baller move. At risk in our world might merely be an anticlimactically unsatisfying wrap-up to one of the most endearingly hilarious and boldly ambitious sitcoms in TV history (rather than a yowling forever made up of bees with teeth and the Kars For Kids jingle)— but that’s more frightening in its own way. Like Eleanor and her friends, we’ve come so far, and to look into the forever-after at The Good Place’s ending and find it wanting is just the sort of pedestrian yet diabolical torment Shawn would come up with in the special Bad Place Peak TV snobs’ torture wing. We’ve come to expect the team’s path to twist and swirl like the Jeremy Bearimy of it all, but putting such a monumental swerve into this one penultimate episode—and then solving it, all in 20-plus minutes—is The Good Place’s riskiest move yet.

They pull it off, naturally. On the creative side, Megan Amram’s script is focused, tight, and ultimately beautifully and blessedly right, while still packing the episode with huge, killer laughs and the sort of spot-on detail work she’s so damned good at. A Good Place lobby greeting our just balloon-arrived heroes is dotted with bowls of party favors, any one of whose secondary qualities humans would fight wars to attain. (Candy that gives you back your 12-year-old energy, headphones that play back every nice thing anyone’s ever said about you without you knowing, ring pops that let you understand Twin Peaks—maybe that one’s just me.) Chidi and Tahani both realize simultaneously that the Good Place congratulatory chime makes you feel exactly like a baby deer is massaging your brain. Eleanor’s ideal party has a plinth reverently housing the bedpan Stone Cold Steve Austin clonged over Vince McMahon’s head that one time. And, of course, Jason’s first impulse when Janet tells them that they can really have or do anything they want is to run off to “Tokyo Drift with monkeys” in go-karts.

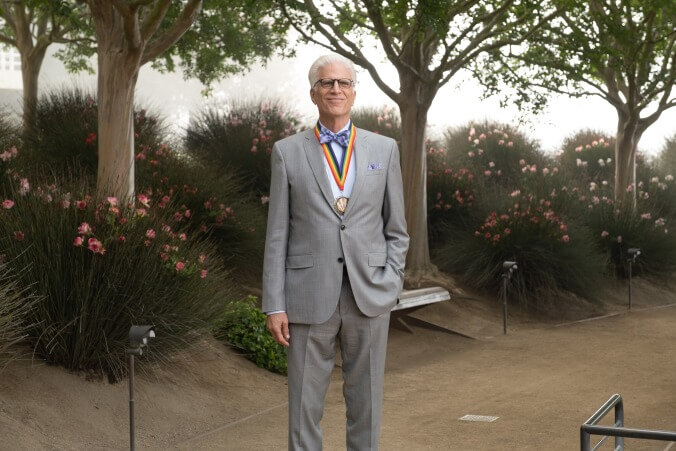

We’re expecting tripwires, but they’re not placed where we think. Michael is unexpectedly nervous upon entering the Good Place’s Silicon Valley campus outer limits, thinking his Chidi-esque tummy-ache is because he’s going to be rejected and possibly expelled for being a demon. (“I bet if you throw up it’ll just be butterflies of something,” says Chidi, helpfully.) That rumbling intensifies when the ever-useless Committee shows up to smilingly usher Michael to a private ceremony where, as Paul Scheer’s Chuck claims, he’s to be made an official Good Place architect, complete with ceremonial robe. But the big twist here (the Committee, getting a relieved Michael to sign a suspicious-looking scroll, immediately quits and splits) is merely a warning trembler to the yawning truth that threatens to swallow up the team right at the finish line.

The Good Place is broken. Or, rather, the Good Place is so perfectly good that it’s broken the very people it was set up to reward. There are plenty of descriptors thrown around all episode to describe the result of a literal eternity of wishes fulfilled and desires anticipated. The former Hypatia works her way through her bliss-fog to explain that her once-ravenous intellect has congealed into a “big, dumb blob.” Eleanor elaborates, calling everyone they meet “a happiness zombie,” and noting that, since everyone is always having constant orgasms they can no longer appreciate, they’ve become “slack-jawed, sweatpants-wearing orgasm machines.” (Sure, that was the dream back in Arizona, but things have changed.) Her affectless voice making the words that much more jarring, Patty tells them, “This place kills passion, and fun, and excitement, and love.” Janet notes that the Good Place’s Janets’ chipper, helpful “Hi there!” is just like hers, but sort of empty, you know? Perhaps most damningly of all, Tahani’s face goes slack with horror as she realizes that, thanks to their fix of the universal apparatus for judging humanity, “millions of people are about to start pouring in, thinking they’re in paradise, only to become a joyless husk.” (“It’s Coachella! We’ve invented cosmic Coachella!” she exclaims, and everyone slumps in despair.)

Well, for a moment anyway. If there’s a theme running through The Good Place’s far-out shenanigans, it’s humanism, and, specifically, friendship. Michael susses out that the Committee sucked so hard at fixing the Good Place because they don’t understand humanity. (Although one white board brainstorming suggestion to wait until Beyoncé dies and have her fix everything shows some insight.) Any system set up to value efficiency and expediency over a true understanding of humanity—with all its attendant contradictions and failings—will turn into a nightmare. So a paradise where all the best of humanity can have everything and look forward to nothing looks great on a white board, but leads to an afterlife of neutered, shuffling half-people, unable even to remember that they’re unhappy about it.

The little detail that makes the solution in “Patty” work so well is so small you’d miss it. Told upon arrival that they could each walk through a portal into the welcoming celebration of their individual dreams, the team—prompted by Tahani—instead links arms and walks through together. Paradise isn’t paradise without the people who got you there. And, sure, that means a ramshackle to-do (Eleanor calls it a “Flori-zona British library extravaganza”) where the caviar is served on Jell-O shots, and a surprising number of uniformed mailmen mingle with people in personalized Jags jerseys, but it also helps the team remember each other and fight off the fog of happiness that threatens to envelop them in a blissfully benign muddle of bottomless shrimp and endless bookcases.

Again, there’s no malice here. The universe wasn’t set up as some sick joke where the virtuous and asshole alike wind up in different but identical hells of their own making. It’s just that the powers that be (or the powers that we’ve seen so far) set up a system for beings it was incapable of understanding. Michael and Janet were part of that system, but their connection with this quartet of restlessly inquisitive knuckleheads finally cracked through their complacent shells and showed them that the truth was a whole lot messier. A whole lot more human. Michael, desperately spitballing, suggests that the intermittent mind-wipe might make the Good Placers happy again, since they could repeatedly forget the bind this endless paradise puts them in. Chidi, noting that that’s just Michael falling back into that old system of thinking, says there must be a better way, since “actual paradise can’t use the same playbook as hell.”

It’s Eleanor who ultimately makes the leap. She reminds Michael of how he was snapped out of his regrettable mid-life crisis phase (red convertible, earring) with Eleanor’s insight that “Every human is a little bit sad all the time because you know you’re going to die. But that knowledge is what gives life meaning.”

So that’s the key, then.

Gathering the mumbling Good Placers around, Michael, Janet, Eleanor, Chidi, Jason, and Tahani all carefully explain that there are going to be some changes. Or, rather, one really big change in the Good Place. There’s a door. You’ll never be forced through it, or pressured to use it. It’s just there. Telling this miserable gathering of all those who made it through the impossible tangle of pain, and circumstance, and injustice, and horror, and fleeting snatches of beauty that is human life and still emerged as the best humanity can be, simply, “It doesn’t seem like this is paradise for you,” Eleanor explains that, if they want it, existence can end. Walk through that door, and, as Janet tells them with reassuring clarity, “It will be peaceful, and your journey will be over.” And so this unlikely team of saviors simply reintroduces the concept of an ending, and sets humanity free.

And the place bursts into spontaneous joy. (Enter the triumphant return of Mr. Music, the D.J.) Is it really that simple? It might be. The Good Place has never accepted platitudes, and so I won’t offer any here, except to say that the lessons of this show have always—always—stayed rooted in the individual. In what’s right for humanity, with no equivocation, and no compromise. That sucks for someone like Chidi Anagonye, whose innate understanding of the insoluble knots of cause and effect and downright mind-grinding contradictions that places us in every second of every day, but it’s why trying to do the right thing is so worthy. Overarching edicts and lofty promises of forever ignore the mess that is us, and inevitably leads to institutional injustice far greater than any crimes it’s intended to punish.

Now there’s a door. You can go through it if you like. Maybe tomorrow, maybe an eternity from tomorrow. As Eleanor Shellstrop and Chidi Anagonye settle onto the comfy-looking sofa of their shared ideal of a home together (they still fight over the blanket), the intimate, insignificant warmth of the domestic scene outdoes the glorious vista their shared window lays out before them. Everything is fine.

Stray observations

- The title of the upcoming last episode echoes what Michael says to the assembled Good Placers when he tells them about the new door, “Whenever You’re Ready.” I am, truly and unashamedly, not ready for the implications of what that means we’re likely to experience there.

- Poor Patty can’t even remember the name of the discipline (“mathematics”) in which she excelled so famously. “Piles?,” is as close as she can get.

- Chidi is disheartened to find out that idols Aristotle, Plato (defended slavery), and Socrates (just annoying) all wound up in the Bad Place, but the prospect of meeting Hypatia bucks him right back up. William Jackson Harper’s delight-squeal is one for the ages.

- Tahani suggests that Big Ben is one of her godfathers, somehow.

- Eleanor, hearing how Chidi had a poster of Hypatia on his wall as a child (it was really Trinity from The Matrix): “Is she the reason why you got beat up so much?” Chidi (excitedly): “She was one of ’em!”

- Tahani attempts conversation with Paltibaal (David Danipour), a former Phoenician do-gooder who tells her blankly how he died because he got a small cut on his finger. Noting that he would have really loved a vaccination, he muses, “It’s crazy that you guys just don’t like them now.”

- Next week: One last door.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.