The good places: The uncommonly decent TV worlds of Michael Schur

Note: This article discusses plot details from the first-season finale of The Good Place.

I don’t want to live in Pawnee, Indiana, but I sure love to visit. For seven seasons on NBC, the small town at the center of Parks And Recreation was one of TV’s most fully realized settings, a Midwestern burg with a history of poorly chosen slogans and strange local fixations. It’s the sort of place whose prominent landmarks have “pit” and “hole” in their names, a hometown that could only inspire pride in the screamingly ignorant or the pathologically optimistic. The latter certainly applies to Leslie Knope, the industrious deputy director of parks and recreation played by Amy Poehler.

And yet, Parks And Rec is reliably one of my favorite TV escapes; a low-simmering, self-centered rage may be the prevailing spirit of Pawnee, but the prevailing spirit of the show itself is more in tune with Leslie. All evidence to the contrary, Leslie believes she hails from the greatest town in the United States, one whose citizens deserve a government that serves their best interests and doesn’t, say, turn a blind eye toward corporations who’d rather serve 512-ounce beverages that take the term “child-sized” literally. The characters’ specific outlooks may differ—Leslie’s touchy-feely liberalism forever conflicted with her friend and reluctant mentor, mustachioed libertarian Ron Swanson—but the protagonists of Parks And Rec were bonded by this call to serve.

It’s a baseline decency that stands in contrast to the rubbish of the world outside those parks department walls, one that makes Pawnee a TV destination worth returning to again and again. It’s the type of world showrunner and co-creator Michael Schur excels at crafting. “I believe in the importance of sincerity and emotion and honesty in TV, even when it’s goofy comedy.” Schur told The A.V. Club in 2012. “Obviously,” he said, with a note of self-deprecation, “this is a gigantic school of thought that dates back to the earliest forms of entertainment”—and you can tease it out of some of the show’s many precursors, tracing it to the White House dream team of The West Wing or the warm, character-focused touch Parks And Rec co-creator Greg Daniels brought to The Simpsons, The Office, and King Of The Hill.

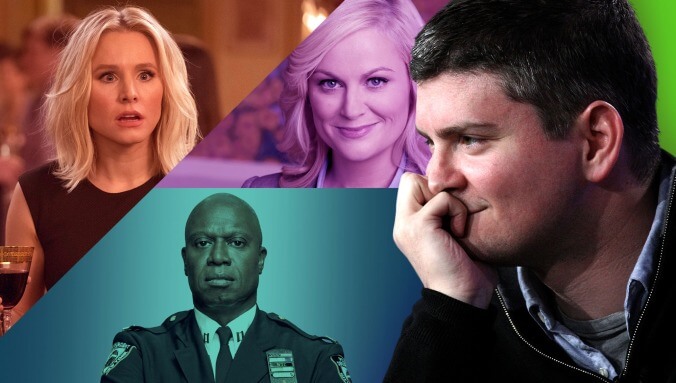

But that belief is the defining trait of Schur’s TV work, as reflected in his subsequent series, Brooklyn Nine-Nine (which he created alongside fellow Parks And Rec alum Dan Goor) and The Good Place, which enter their respective fifth and second seasons this fall. Part of what’s inviting about these shows’ settings is their idealized nature: It’s embodied in Leslie Knope, the dedicated civil servant doing everything in her relatively limited power to improve the lives of citizens who insist on wrapping their entire goddamn mouths around water-fountain spouts. It’s in Brooklyn Nine-Nine, a cop comedy airing at a time when the face of policing in America is anything but sincere, emotional, or honest. And it’s in The Good Place, a high-concept charmer whose characters spent their first season poking and prodding the virtues expressed and possessed by their predecessors in Pawnee and Brooklyn.

That show’s initial setup was Parks And Rec turned inside out: Eleanor Shellstrop (Kristen Bell) is the “selfish ass” accidentally admitted to paradise, where she’s surrounded by selfless people who gave their time, their wealth, and in at least once case, their vital organs to those in need. Such good deeds are tallied up to determine whether a person goes to The Good Place or its hellish corollary, The Bad Place, after they die. It was an early indication—along with Eleanor’s bookkeeping snafu—that something might be amiss. Nonetheless, The Good Place differed from Parks And Recreation and Brooklyn Nine-Nine in that it wasn’t just the people who made me want to visit every week. In this case, I wouldn’t have minded living where they lived—at least at first.

That draw was smartly laced into the first season, which is all about Eleanor doing what she can to remain in the utopian half of the afterlife. What begins as an attempt to pass herself off as one of the righteous becomes a legitimate quest to retroactively save her soul. With the assistance of her Good Place-designated soulmate, the late professor of ethics Chidi Anagonye (William Jackson Harper), Eleanor gets a crash course in human decency, learning the academic principles that gird the principals on Parks And Recreation and Brooklyn Nine-Nine. It’s as much fun as one can have with T.M. Scanlon’s What We Owe Each Other and the other dense texts that Schur boned up on in preparation for the show.

It’s a novel little spool around which to wrap a goofball ensemble sitcom, but the ingeniousness of the first season was all in the unraveling. Turns out Chidi has some work to do on himself as well (his academic rigorousness doubles as a frightful and injurious indecisiveness), and The Good Place isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, either. In a twist that wrenches partially because The Good Place never presented itself as a source for wrenching twists, the finale reveals that what we’ve seen of The Good Place is, in fact, an experimental prototype from the demons who run The Bad Place, where Eleanor, Chidi, and their neighbors—the celebrity philanthropist Tahani Al-Jamil (Jameela Jamil) and the living manifestation of the “Florida Man” meme, Jason Mendoza (Manny Jacinto)—are supposed to torture one another for eternity.

It’s a clever move narratively, but because of the foundation The Good Place has laid and the creative reputation that precedes it, the impact is felt most deeply on an emotional level. Here was a manifestation of the sincerity and the honesty that marks Schur’s other TV worlds, crumbling to dust. The tables turn on a wickedly maniacal laugh from Ted Danson, who’d spent 12 episodes in the disguise of an avuncular divine messenger. (The creator of this world, he is named, not coincidentally, Michael; the finale is titled “Michael’s Gambit.”) Following the finale, TV critic Emily Nussbaum responded in the pages of The New Yorker (with a wink to The Good Place’s playful way of bowdlerizing curse words):

“After watching nine episodes, I wrote a first draft of this column based on the notion that the show, with its air of flexible optimism, its undercurrent of uplift, was a nifty dialectical exploration of the nature of decency, a comedy that combined fart jokes with moral depth. Then I watched the finale. After the credits rolled, I had to have a drink. While I don’t like to read the minds of showrunners—or, rather, I love to, but it’s presumptuous—I suspect that Schur is in a very bad mood these days. If Parks was a liberal fantasia, The Good Place is a dystopian mindfork: It’s a comedy about the quest to be moral even when the truth gets bent, bullies thrive, and sadism triumphs.”

In one swift, sickening turn, The Good Place gains several shades of complexity, and they color the second season of the show in ways that were unforeseeable a year ago. (NBC sent the first four episodes to critics ahead of the premiere; they’re pretty great—the third has an impressive amont of fun with the new status quo.) They’ve also renewed my appreciation for the times when the settings of Parks And Recreation and Brooklyn Nine-Nine look a little less like little slices of The Good Place on earth. Parks And Rec indulged a certain amount of wish-fulfillment in its later years—forecasting an enshrinement of its progressive values that, sadly, didn’t come to pass—but the show introduced plenty of truth-benders, bullies, and sadists to challenge Leslie’s faith in governance and community. The community occasionally filled all three roles simultaneously, in the form of the roving comment section that attended public meetings and visited city hall to loudly petition for time-capsule inclusions, tax exemptions, and permits for “missing bird” fliers. (“There’s no time! He can fly!”)

A few months after “Michael’s Gambit,” Brooklyn Nine-Nine took its own risk, puncturing its rosy view of the NYPD with an episode concerning racial profiling. In “Moo Moo,” Detective Sergeant Terry Jeffords (Terry Crews) searches his neighborhood streets for his daughter’s lost blanket, only to be stopped-and-frisked by a white patrolman. Like The Good Place and its finale, “Moo Moo” uses what we take for granted about Brooklyn Nine-Nine and reverses it to make an emotionally effective point: Just because the main characters on the show are good cops, it doesn’t mean everyone they work alongside is. This kicks off a complicated dialogue between Terry and his commanding officer, Captain Raymond Holt (Andre Braugher); Holt tells Terry not to file a report on the incident, Terry presses Holt on why. The scene that ensues deftly juggles the depth with which the performers have gotten to know their characters, the personal histories the show has woven for them, the fact that Brooklyn’s two highest ranking officers are played by actors who are black, and several variations on the word “besmirched.” It’s stunning work all around.

“We didn’t want it to feel like a completely different, special episode,” Dan Goor later told Uproxx’s Alan Sepinwall. That said, “Moo Moo” has an impact because of the ways it doesn’t resemble the average Brooklyn Nine-Nine. The officer who harasses Terry upsets the balance of the show’s idealized world; “Moo Moo” draws a great deal of drama (and a little bit of humor) out of the characters attempt to restore that balance. It’s something they can’t fully restore, but the episode still ends on a note of celebration and poignancy between Crews and Braugher.

The good places in the Michael Schur catalogue aren’t impenetrable fortresses, and the shows that are set there aren’t guaranteed escapes from the demons, the cranks, or the racist cops that populate our world. But even at the bottom of the deepest, darkest pit, there’s bound to be sincerity, emotion, and honesty. For viewers living in a world that looks increasingly like The Bad Place, that counts for a lot.