Capturing its eponymous era through the prism of two lives caught in its grinding gears—and in the vice grip of their own passions—Cold War achieves something rare and coveted: the perfect fusion of the political and the personal. Make that the overtly personal. Pawlikowski’s last movie, the Oscar-winning Ida, brought him back to his homeland, which he fled as a teenager in the early 1970s, for a story actually about going home. In many respects, Cold War picks up where that film left off: Shooting again (at least partially) in his native Poland and in sumptuous black-and-white, the filmmaker returns to the ruins of a country ravaged by war. This time, though, he’s forged a more explicit connection to his own life, spinning a tortured, on-again/off-again love story that’s modeled—in dynamic if not specific detail—on the relationship between his own parents.

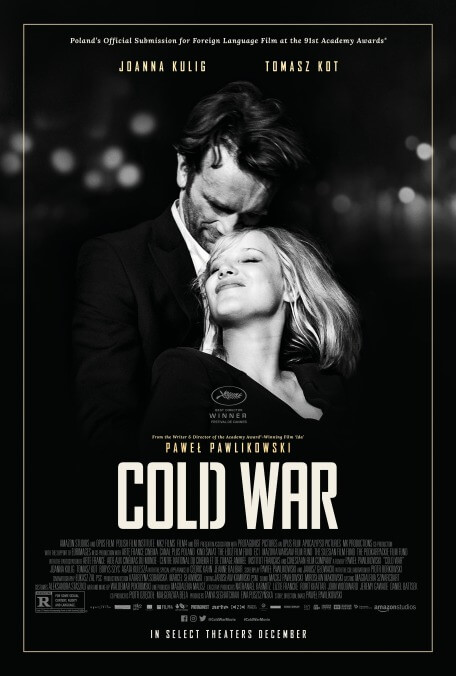

He’s even used their real names. Wiktor (Tomasz Kot) meets Zula (Joanna Kulig) in 1949, during an audition in a bombed-out Orthodox church. He’s a composer, creatively unmoored, who’s crossing Poland in a van with another musician, Irena (Agata Kulesza, who played the protagonist’s jaded aunt in Ida), assembling a traveling folk ensemble that will bring “the music of the people” to the people. She’s a young singer from the city, masquerading as a simple mountain girl to get the gig, a survivor outrunning a rocky past. (Asked about rumors that she stabbed her father, Zula explains: “He mistook me for my mother so I used a knife to show him the difference.”) The two certainly don’t look like a perfect match (he towers over her, gangly to her petite radiance), and they’re even less temperamentally suited to each other. Untenable on its best days, destructive on its worst, their relationship does not seem built to last.

Eventually, the lovers are separated by forces larger than themselves. Mazurek, their increasingly popular music group—based on the real Polish folk collective Mazowsze—is coopted by the Communist government, transformed against Irena’s objections (“The rural population doesn’t sing about land reform”) into just another arm of the Soviet propaganda machine. Wiktor flees to France to escape the tightening grip of Stalinism. Zula stays behind, embracing the relative perks of her newfound stardom. Yet as the years blur by—Cold War denoting each time jump with a blackout—something keeps drawing the two together again. Unable to live with or without each other, they dance back and forth across the Iron Curtain, breaking up and reuniting as the world changes rapidly around them. Somewhere around 1954, they make a new start in the burgeoning jazz clubs of Paris. But though it’s a bohemian paradise, they’re both miserable; their love only seems to thrive when endangered or when absence has made their hearts grow fonder. (If the film has a signature motif, it’s of Wiktor or Zula looking up to see the other standing again in the doorway of their life, like Ilsa ghosting into Rick’s Café).

More than “old-fashioned” in its elegance, Cold War is a time machine of a period piece, vivid as a photographic memory in its vision of midcentury Europe, from the smoky (but somehow dissatisfying) glamour of the West to what it depicts as the colder austerity and decay of the East. What we’re seeing—in the background of every spat or passionate embrace, in fragments and illustrative glimpses—is a world lurching headlong into the modern age. Pawlikowski often conveys this rapid change, as well as the discrepancy between different places, through his music choices: The soundtrack, a mixtape of cultural transition, moves from ragtag rural sing-alongs to bebop piano to tacky big-band socialist pop. One particular song, a Polish folk standard called “Two Hearts,” keeps getting covered and transformed, culminating in a scene of Zula, now in full chanteuse mode, crooning a seductive lounge version in Paris. Later, she’ll launch herself onto the dancefloor to the tune of “Rock Around The Clock”—perhaps the perfect way to eulogize the old world and usher in a new one.

There are shots in this movie so monochromatically gorgeous that you want to crawl inside them, even at the risk of being swallowed whole by the film’s melancholy. Pawlikowski is working in roughly the same style as Ida, framing his actors through an intimately boxy aspect ratio and pristine, contrast-heavy black-and-white. (With the two films, cinematographer Lukasz Zal has elevated himself to the upper echelons—he crafts images worthy, in their shimmering and symmetrical beauty, of museum exhibition.) But in Cold War, the reverent stillness, the meticulous near-perfection, of Pawlikowski’s craft is disrupted by the musical and physical force it captures, the star erratically careening through his frames. Kulig, who had a small role in Ida, delivers a remarkable performance. Giving off hot embers of passion and cutting disdain (“It’s you I don’t believe in,” she tells Wiktor during one of their spirals into toxic incompatibility), her Zula is a one-woman cultural revolution, the face of a Europe—bloody but breathing—that clawed its way out of the rubble of World War II.

So is Wiktor and Zula’s combative love affair, their Sam and Diane routine, a metaphor for the sea change of the Cold War itself? Or is the constant turmoil of midcentury Europe—the making and remaking of nations, the flow of bodies across borders—the actual metaphor, reflecting this pair’s relationship, the kind that’s always on the brink of collapse, sustained only by its struggle? Maybe it’s both at once. Either way, Pawlikowski, an immigrant who’s built an interesting multinational career—his other films include the British coming-of-age romance My Summer Of Love and the bizarre international coproduction The Woman In The Fifth—has this time offered a expat’s vision of Europe. In Cold War, together and apart become proxies for exile and return. When you can’t live with or without someone, is the agony the same as the siren call back home, no matter what awaits you there? This classical triumph works on the macro and the micro level, on the personal and the political one. That it does so in a cool hour and a half is a marvel of brevity, a lost virtue of yesterday.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)